- Home

- Publications

- PAGES Magazine

- Towards The Prediction of Multi-year To Decadal Climate Variability In The Southern Hemisphere

Towards the prediction of multi-year to decadal climate variability in the Southern Hemisphere

Scott Power, Ramiro Saurral, Christine Chung, Rob Colman, Viatcheslav Kharin, George Boer, Joelle Gergis, Benjamin Henley, Shayne McGregor, Julie Arblaster, Neil Holbrook, Giovanni Liguori

Past Global Changes Magazine

25(1)

32-40

2017

Scott Power1, Ramiro Saurral2, Christine Chung1, Rob Colman1, Viatcheslav Kharin3, George Boer3, Joelle Gergis4, Benjamin Henley4, Shayne McGregor5, Julie Arblaster5, Neil Holbrook6, Giovanni Liguori7

Introduction

Multi-year (2-7 years) and decadal climate variability (MDCV) can have a profound influence on lives, livelihoods and economies. Consequently, learning more about the causes of this variability, the extent to which it can be predicted, and the greater the clarity that we can provide on the climatic conditions that will unfold over coming years and decades is a high priority for the research community. This importance is reflected in new initiatives by WCRP, CLIVAR, and in the Decadal Climate Prediction Project (Boer et al., 2016) that target this area of research. Here we briefly examine some of the things we know, and have recently learnt, about the causes and predictability of Southern Hemisphere MDCV (SH MDCV), and current skill in its prediction.

Causes of SH MDCV

As with other parts of the globe, internally generated climate variability is a major element of SH MDCV (Kirtman et al., 2013). Major components of internal variability for the Southern Hemisphere are decadal variations in ENSO, the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO, Garreaud and Battisti, 1999; Power et al., 1999; Salinger et al., 2001; Folland et al., 2002; Wu and Hsieh, 2003; Holbrook et al., 2011; Christensen et al., 2013; Kosaka and Xie, 2013; England et al., 2014; Holbrook et al., 2014; Watanabe et al., 2014; Henley et al., 2015; Meehl et al., 2016), the Southern Annular Mode (SAM (Shiotani, 1990; Thompson et al., 2000; Watterson, 2009; Pohl et al., 2009; Yuan and Yonekura, 2011; Jones et al., 2016), and the Indian Ocean Dipole.

North Pacific decadal variability has recently been described by Di Lorenzo et al. (2015) as a seasonally-based red noise process involving the interaction between extratropical atmospheric variability and ENSO via the North Pacific Meridional Modes (Chiang and Vimont, 2004). Although a similar mechanism has not yet been proposed for the South Pacific DCV, tropical-extratropical interactions, including via both the ocean and atmosphere, are thought to be at least partly responsible for inducing decadal to multidecadal variability in the South Pacific too (e.g., McGregor et al., 2007, 2008, 2009a and b; Farneti et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Ding et al., 2015). Inter-basin interactions are also thought to play a role in driving Pacific Ocean decadal and multi-decadal variability (e.g., McGregor et al., 2014; Kucharski et al., 2016, Chikamoto et al., 2016). Palaeoclimate reconstructions of MDCV in the Pacific vary significantly in their spectral characteristics, likely due to spectral biases in the different proxy records, non-stationarity of teleconnections and the use of various statistical reconstructions methods (Bateup et al., 2015).

External forcing, both natural and anthropogenic, can also drive decadal and longer-term variability in the SH (e.g., Bindoff et al., 2013 and references therein). Natural drivers include volcanic eruptions (e.g. Church et al., 2005), while anthropogenic external drivers include changes in greenhouse gas concentrations, aerosols (Cai et al., 2010) and stratospheric ozone (Kirtman et al., 2013; Arblaster et al., 2014; Eyring et al., 2013).

How well do climate models simulate MDCV in the SH?

The ability of climate models to simulate Earth's climate was assessed in the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (Flato et al., 2013). They concluded that models reproduce many important modes of variability. This includes modes of relevance to the SH: ENSO, the Indian-Ocean Dipole and the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation. Models have improved in some respects since the last generation although, in the case of ENSO, some of this improvement might not be entirely for the right reasons.

While models are extremely valuable tools that enable us to improve our understanding of SH MDCV, they are not without their limitations. For example, while CMIP5 models tend to capture the spatial pattern of the IPO, models tend to underestimate the magnitude of SST variability associated with the IPO (Power et al., 2016; Henley et al., 2017), and both the magnitude of DCV in trade winds (England et al., 2014; McGregor et al., 2014) and multidecadal changes in the strength of the Walker Circulation (Kociuba and Power, 2015). These deficiencies appear to be due, at least in part, to modeled ENSOs that tend to be too oscillatory on too short a time-scale. This makes it hard for the models to maintain multi-year and longer-term anomalies (Kociuba and Power, 2015; Power et al., 2016).

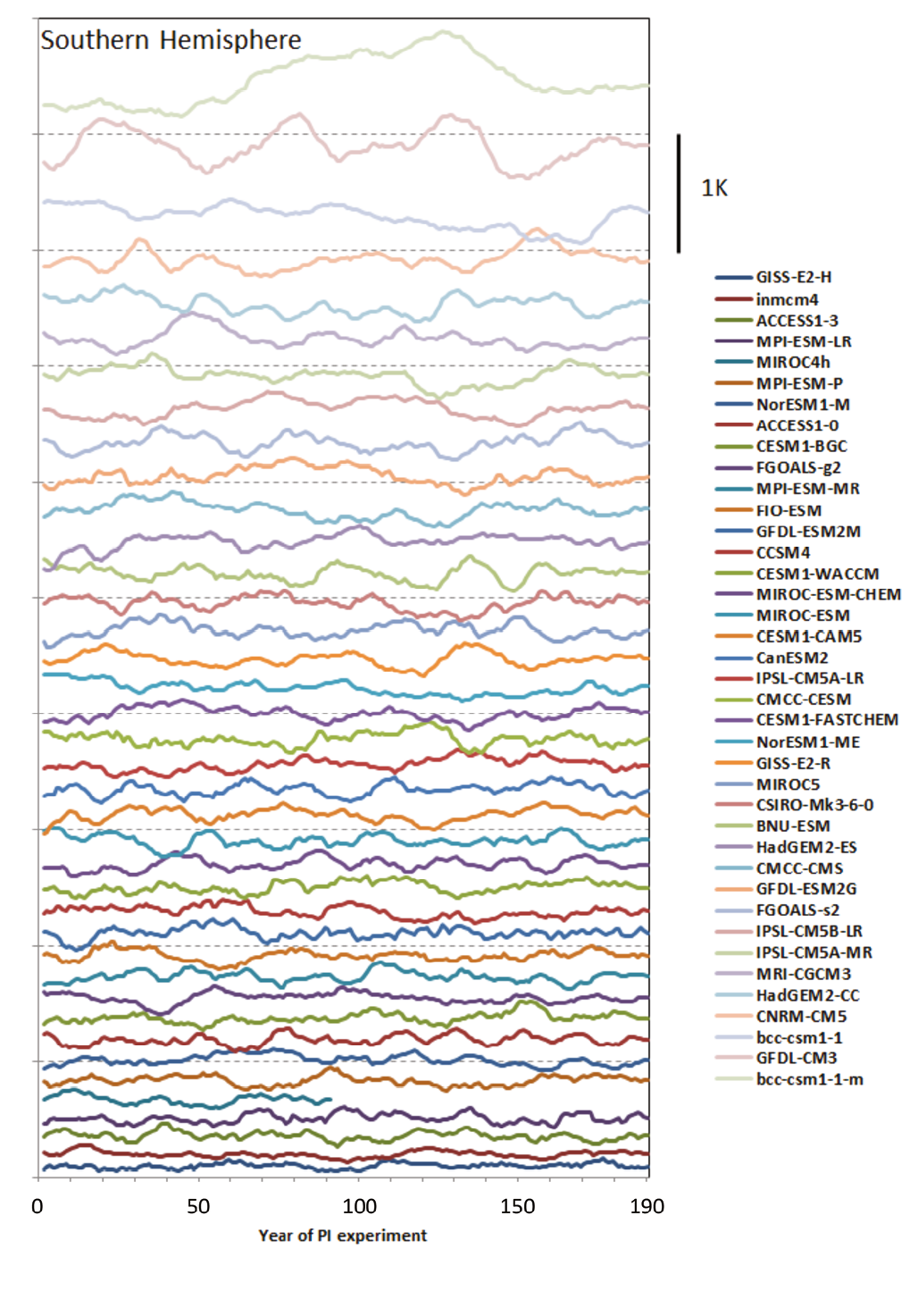

A further illustration of the limitations of CMIP5 models in simulating SH MDCV is seen in Fig. 1. It shows time-series of the decadal variability in SH surface air temperature from pre-industrial runs of CMIP5 models. The model-to-model range in the magnitude and character of the variability is remarkable. Some models exhibit variability that has a range of a few tenths of a degree, while the range of some other models is three or more times larger. The character of the variability also differs markedly among models. In some models there is pronounced multi-decadal variability, whereas in other models variability occurs on much shorter time-scales. While further research is needed to ascertain which of these simulations more realistically captures SH MDCV. Clearly, given the large model to model differences evident in Fig.1, care is needed in assigning confidence to conclusions drawn on the basis of SH MDCV simulated in the current generation of climate models.

There have been other studies investigating SH MDCV of the past 1000 years in climate model simulations and reconstructions For example, a recent study by Hope et al. (2016) examined the decadal characteristics of ENSO spectra based on seven published ENSO reconstructions, and indices of Nino 3.4 SSTs and the Southern Oscillation Index calculated from six CMIP5–PMIP3 last millennium simulations. The post-1850 spectrum of each modelled or reconstructed ENSO series captures the observed spectrum to varying degrees. However, no single model or ENSO reconstruction completely reproduces the instrumental spectral characteristics across the multiyear or decadal bands.

Appreciable changes in the level of decadal ENSO variability is observed in the reconstructions and simulations of the pre-1850 period. While much of this represents internally generated variability (see e.g. Power et al., 2006), some of the variability may be linked to intermittent major volcanic eruptions (Hope et al., 2016). Nevertheless, Hope et al. (2016) report inconsistencies between reconstructions, models and instrumental indices used to evaluate changes over past centuries, reflecting the complexity of reconstructing and simulating past changes of a highly variable coupled system. In the reconstructions, variability arises from internal climate processes, different forced responses, or non-climatic proxy processes that are still not well understood (Ault et al., 2013).

Improving the simulation of SH MDCV would be greatly assisted by the availability of additional data from high latitude regions. The palaeoclimate reconstruction of the SAM by Abram et al. (2014) displays good agreement with CMIP5–PMIP3 last millennium simulations. Although the reconstruction shows a progressive shift towards SAM's positive phase as early as the fifteenth century, the positive trend in the SAM since 1940 is reproduced by multi-model climate simulations forced with rising greenhouse gas levels and ozone depletion (Abram et al.. 2014). These results are likely to reflect the brevity of the instrumental data from high latitudes, and associated deficiencies in model representation of SH climate (Jones et al., 2016).

Predictability of MDCV in the SH

In climate science the term “predictability” has a different meaning to “predictive skill”. Predictability provides an estimate of the upper limit to predictive skill, in the absence of technical problems - apart from uncertainty in initial conditions. Predicability is usually estimated from a model’s ability to predict its own evolution given imperfect initial conditions. The presumption is that the results from a well-behaved climate model can provide information on the predictability of the actual climate system. Predictability arises from internal variability, external forcing (e.g. increasing greenhouse gas concentrations), and interactions between them. One estimate of the relative importance of initial conditions and external forcing for the predictability of time-averaged temperature in the Southern Hemisphere is depicted in Fig. 2 (dashed lines). Initialisation provides additional potential skill on average over the southern hemisphere on all time-scales, from one month to 10 years. The relative contribution of initialisation to the potential skill tends to diminish the longer the time-scale, as the relative contribution from external forcing increases.

The estimated potential predictability of five-year means across the SH is dominated by the contribution of external forcing, with internal variability making comparatively little contribution (Kirtman et al., 2013, Fig. 11.1). This is consistent with the findings of Meehl and Hu (2010), with the possible exception of the east Antarctic region south of Africa. Whether or not this represents a robust exception remains unclear.

Additional studies have examined the regional predictability of MDCV in the SH using idealised experiments in which model conditions are perturbed at a particular point in time in an integration and the degree to which the ensuing variability is affected is assessed. Power and Colman (2006) used this strategy to assess the predictability on internally generated variability in their climate model. They found that off-equatorial regions in the South Pacific exhibited variability that was a delayed, low pass-filtered version of preceding ENSO variability. The ocean had acted as a low pass filter on the wind-stress and heat flux forcing it received, in an ENSO-modified Frankignoul and Hasselmann process (Hasselmann, 1976; Frankignoul and Hasselmann, 1977). At ocean depths of 300 m, this gave rise to highly predictable multi-year variability. This is consistent with the findings of Shakun and Shaman (2009), who showed that the leading mode of SST variability in the South Pacific could be reasonably well-simulated as a response to preceding ENSO-driven heat flux forcing, in analogy with the Pacific Decadal Oscillation in the North Pacific (Newman et al., 2003; 2016).

Power et al. (2006) used the same strategy and concluded that there is limited predictability in interdecadal changes in ENSO activity and its associated teleconnections to Australian climate. More recently, Wittenberg et al. (2014) concluded that potential predictability was evident in ENSO variability in their model several years ahead, but not on decadal time-scales. Power and Colman (2006) also concluded that the relative influence of decadal variability on ocean variability as a whole tended to be weak in the tropical Pacific and more pronounced as depth and latitude increased. This general pattern is consistent with the more recent analysis of predictability in SST (Frederiksen et al. 2016).

The excitation of Rossby waves from ENSO-driven wind-stresses also drives subsequent and therefore predictable sea-level variability (e.g., Luo, 2003; Qiu and Chen, 2006; Holbrook et al., 2011; 2014). Other studies have examined lagged associations with extra-tropical regions and the tropics, with results suggesting that South Pacific driven changes in both the ocean and atmosphere may provide a source of predictability for multi-year variability in the tropics (McGregor et al., 2007, 2008, 2009a and b; Luo et al., 2003; Tatebe et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014). For example, Zhang et al. (2014) identified a South Pacific meridional mode in idealised climate simulations, in which wind variability in the South Pacific underpins a sub-component of subsequent climatic variability in the tropics, while the studies of McGregor et al. highlight ocean links between the extra-tropics and the tropics and their role in driving climate variability in the tropics.

More recently, the re-emergence of remnant mixed layers to the surface has been identified as a possible source of predictability for SH MDCV (D. Dommenget, pers. comm.). Finally, predictability may arise in the Pacific, including the South Pacific, via atmospheric teleconnections driven by partially predictable Atlantic surface temperature variability (e.g. Rashid et al., 2010).

Prediction of SH MDCV

Unlike “predictability” assessment, a “prediction” is an estimate or collection of estimates of the future state of the real world. Research on decadal climate prediction (Smith et al., 2007; Meehl et al., 2009; Meehl et al., 2016) aims to provide forecasts of MDCV. Part of the scientific basis for producing such predictions is given by the predictability that exists in some areas and for some variables, as discussed in the previous section. MDCV prediction research was an important element of the Fifth Phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5) (Taylor et al., 2012) and was a subject assessed in the Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC (Kirtman et al., 2013). CMIP5 provided a new set of forecasts that were initialized using the observed state of the climate system. This allowed an assessment of the benefit of initialization by comparison with parallel experiments where no information on the initial state of the climate system was provided. The quantification of such changes is important since near-term climate predictions are affected by the initial conditions as well as by changes in the external forcing (Meehl et al., 2009; Kirtman et al., 2013; Meehl and Teng 2016).

Initialization, which is accomplished using a range of different techniques (e.g. Hawkins and Sutton, 2009, 2011; Mochizuki et al. 2010; Doblas-Reyes et al., 2011), produce ensembles of simulations which are intended to account for uncertainties in the initial conditions. As with any other forecast, a set of skill scores is usually computed to quantify the quality of such predictions for previous years (i.e. prediction of past years or hindcasts), providing a quantitative assessment of the performance of the different forecast systems.

In spite of the relative youth of this research area, there are a growing number of papers that address predictability and prediction skill over areas of the Northern Hemisphere (e.g. Griffies and Bryan, 1997; Boer, 2000; Collins, 2002; Hawkins and Sutton, 2009; Smith et al., 2010; Zanna, 2012; García-Serrano and Doblas-Reyes, 2012; Boer et al., 2013; Guémas et al., 2013; among many others). However, considerably less attention has been paid to the SH. Part of the explanation is likely related to the smaller scientific community that exists in the SH compared to the northern hemisphere. Most importantly, there is a relative lack of in situ climate records in most of the SH, with the exception of some ship routes in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans. Limited in situ data poses a difficulty for the assessment of SST variability and prediction skill. The advent of the satellite era increased the amount of available information, but since that source of data only exists since the late 1970s or early 1980s, most of the SST hindcasts prior to the 1970s cannot be validated against ground truth, thus decreasing the sample size and significance of most of the statistical tests applied therein. In an assessment of the decadal climate prediction skill over southern Africa, Reason et al. (2006) had already noticed how the lack of data and the decrease in density and quality of the information in several regions in Africa was a major concern.

The relative importance of initial conditions and external forcing for the skill of existing hindcasts of time-averaged temperature in the Southern Hemisphere is depicted in Fig. 2 (solid lines). Initialisation provides additional hindcast skill over the Southern Hemisphere for averages of up to three years, beyond which initialisation in current systems appears to have little impact. The difference between the actual skill scores (solid lines) and the potential skill scores (dashed lines) suggests that greater skill may be achieved as the technical issues associated with MDCV prediction are overcome.

Among other recent contributions to this topic, Rea et al., (2016) quantified prediction quality over high SH latitudes, concluding that a proper representation of the stratospheric processes and the stratosphere-troposphere coupling is crucial in order to obtain skillful predictions. Saurral et al., (2016) analyzed the influence of initialization and climate drift on hindcasts of SST in the South Pacific in a set of coupled GCMs. They noticed differences in the hindcast skill depending upon initialization under strong or weak ENSO conditions. Overall, their results showed lower skill in decadal predictions than that found for the North Pacific basin (Lienert and Doblas-Reyes, 2013).

The increased number of observations that are being made in the SH, particularly of the ocean’s surface and sub-surface through e.g. the Global Temperature and Salinity Profile Programme, ARGO, and other critical elements of the global observing network, will provide invaluable data for the assessment of predictability and prediction skill in coming years. At the same time, modelling efforts focused on improving the representation of processes underpinning decadal variability and initial conditions are also of great importance for the field. The prediction of SH MDCV could benefit from the improvements in sea ice concentration and thickness reanalysis and the ingestion of those data into the GCMs. For instance, the upcoming Year of Polar Prediction could prove a very interesting opportunity to gather new information on sea ice in order to improve understanding of high-to-mid latitude linkages and to see how these new observations impact the skill of MDCV predictions.

Making further progress

Our understanding of the causes and predictability of MDCV in the Southern Hemisphere and our ability to predict its behavior could be increased by improving, e.g.:

- the documentation, quality controlling and analysis of MDCV evident in instrumental records, other historical records (see, e.g. Callaghan and Power, 2011; 2014), and paleo records

- the quality and increasing the range of relevant instrumental, historical and paleoclimate records.

- our understanding of the impact/sensitivity of methods used for multi-proxy paleoclimate records in order to develop methods that are not sensitive to the non-stationarity of teleconnections.

- climate models and their simulation of observed SH MDCV, including the underlying dynamical processes and statistics of SH MDCV and particular important events (e.g., strengthening the of Walker circulation over the past few decades and the rate of warming in the Pacific over the past half-century)

- understanding of the causes of SH MDCV through e.g. process studies, by continuing to develop theoretical understanding of the relevant processes involving both observations and model simulations, using a hierarchy of modelling approaches

- understanding of MDC predictability and its underlying dynamics in models, through further experimentation and further analysis of experiments already conducted

- initialisation methods, and predictive systems more broadly

- our ability to reliably determine hindcast skill.

These objectives can be assisted by, e.g.:

- participation in CMIP6, the Decadal Climate Prediction Project and other relevant international initiatives

- maintaining and expanding observing networks to better monitor SH MDCV

- continuing to foster links between paleoclimate, climate modelling and model analysis communities

- digitising and quality controlling early instrumental records from SH locations (Allan et al., 2016; Freeman et al., 2016), and by

- collecting critical palaeoclimate data in key regions (e.g. Abram et al., 2015).

affiliations

1Bureau of Meteorology, Australia

2CIMA, Ciudad Universitaria, Argentina

3Environment and Climate Change, Canada

4University of Melbourne, Australia

5 Monash University, Australia

6University of Tasmania, Australia

7Georgia Institute of Technology, USA

references