- Home

- Taxonomy

- Term

- PAGES Magazine Articles

PAGES Magazine articles

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2024

Past Global Changes Magazine

Falster G.M.![]() 1,2 and PAGES Early-Career Network Steering Committee Members*

1,2 and PAGES Early-Career Network Steering Committee Members*

Early-career researchers (ECRs) are important contributors to global change research (e.g. Andersen 2023). To support the development of ECRs, there are funding and opportunities available only to ECRs. Additionally, "early-career" status allows researchers the freedom to gain experience across various aspects of their careers and provides a foundation for a global community of developing paleoscience researchers.

However, the definition of "early-career researcher" varies between relevant scientific organizations. For example, PAGES defines an ECR as an undergraduate or postgraduate student, or a scientist within five years of completing their PhD. The European Geosciences Union defines an ECR as a student, PhD candidate or practicing scientist who received their highest degree within the past seven years. The American Geophysical Union defines an ECR as a scientist who received their highest degree within the past 10 years. Each institution allows flexibility for career breaks.

In 2023, the PAGES Early-Career Network (ECN) ran a survey seeking input from self-identified paleoscience ECRs on what they consider to be the meaning of the term "early-career researcher" (Fig. 1). The 66 responses were highly varied, falling into three broad groups. Approximately one quarter of respondents defined ECR based on employment status. Another quarter suggested a more nuanced definition. Most of the remainder based their definition on a certain number of years since award of a researcher’s highest degree (ranging from three to 15 years). Among those defining ECR by "years post degree", only two explicitly mentioned career interruptions (e.g. parental or carer leave, or COVID-19).

|

|

Figure 1: Career stage of the 66 survey respondents, and summary of responses to the question: In your own words, what would you consider to be the meaning of "early-career researcher"? |

Of the respondents defining ECR by employment status, most suggested that ECRs are researchers who have not secured permanent jobs. By contrast, respondents suggesting more nuanced definitions generally felt that ECR status can result from more qualitative indicators, including a limited publication record, working under more senior academics, having limited experience, still developing skills and collaborations, and still establishing their research direction and identity.

Several respondents stated the importance of self-identification, implying there is a strong mentality component to being an ECR. A further 10 respondents indicated that part of being an ECR is the requirement of support from ECR groups and/or more experienced academics — and that ECRs are researchers who are still learning, and who have the right to make mistakes.

An important question, then, is: What distinguishes early- from mid-career researchers? One key aspect is eligibility for opportunities only available to ECRs. But evidently, there are more nebulous aspects to this transition, such as a feeling of readiness and independence, or acquiring a certain level of knowledge and experience. In any case, we would argue that: 1) the need for support; and 2) continued learning are constants throughout an academic’s career. In the words of the lead author: "As someone who is approaching five years post-PhD, I am still learning as much as I did as a student, and I certainly still make mistakes."

Finally, there is also variability as to when members of the ECR community believe one becomes an ECR. Survey responses ranged from "when you start doing research" to "recently finished a PhD". The prevailing opinion was that any student undertaking research — including undergraduate researchers, Masters students, and PhD candidates — should be considered an ECR until they stop active research, or transition to mid-career researcher.

In summary, results of our survey demonstrate that paleoscience ECRs lack a coherent global identity. It is possible that this reflects variability in institutional definitions of an ECR, which may in turn be because the definition needs to be somewhat fluid. "Hard" definitions (accounting for career breaks) are required to ensure funding reserved for ECRs is awarded to ECRs, but on the other hand, guidance, mentoring and peer support should be available to anyone who feels they need it. Understanding that there is variability within the way the global paleoscience ECR community views itself may help ECRs better understand their "place" in the academic community, and to modulate their expectations of themselves, and of their peers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article summarizes responses to a survey run by the PAGES Early-Career Network (ECN) in March 2023. We thank all participants for their thoughtful responses.

affiliationS

1Research School of Earth Sciences, Australian National University, Australia

2ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes, Sydney, Australia

*PAGES Early-Career Network Steering Committee Members

Sudhir Bhadra (Indian Institute of Science, India)

Fernanda Charqueño Celis (Comahue University, Argentina)

Patrick Cho (University of Notre Dame, USA)

Aditi Dave (ERC PROGRESS Babes- Bolyai University, Romania)

Kamila Faizieva (University of Vienna, Austria)

Georgy Falster (The Australian National University, Australia)

Alexandra Fazekas-Németh (GADAM Center of the Silezian University, Poland)

Olga Gildeeva (Friedrich-Schiller University, Germany)

Ignacio Jara (CEAZA Scientific Centre, Chile)

Juliana Nogueira (Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Czech Republic)

Christine Omuombo (The Technical University of Kenya, Kenya)

Jessie Pearl (The Nature Conservancy, USA)

Lena Thöle (Utrecht University, Netherlands)

contact

Georgy Falster: georgina.falster anu.edu.au

anu.edu.au

references

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2024

Past Global Changes Magazine

Varga L.![]() 1, Filippova A.

1, Filippova A.![]() 2, Kaushal N.

2, Kaushal N.![]() 3 and Koren G.

3 and Koren G.![]() 1

1

The availability of paleorecords is fundamental for studying past climate and human activities. Here we report on the availability of paleo data in Brazil, a country with diverse landscapes including rainforests, savannas and wetlands. Within Brazil, our main focus is on the Amazon region, a key region for carbon sequestration, regional water supply, a hotspot for biodiversity, and home to current and past Indigenous cultures.

We have evaluated the availability of paleorecords in Brazil from four widely used repositories: (1) NOAA’s World Data Service for Paleoclimatology; (2) Neotoma Paleoecology Database; (3) PANGAEA Data Publisher for Earth & Environmental Science; and (4) various datasets collected by PAGES working groups. This approach largely follows the analysis performed for India (Kaushal et al. 2021) that appeared in an earlier issue of Past Global Changes Magazine.

For each data record retrieved from the databases, we first checked for duplication: we did not add another entry if the record already existed in our overview. Further, we noted the name, coordinates (latitude, longitude) and the archive type. In total, we found 366 paleorecords for 21 different archive types. The most abundant archive types are charcoal (161), shells (67) and pollen (32). A full list is available via Zenodo (doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10466814).

We also plotted the data on a map (Fig. 1). Initially, this resulted in cluttering and overlapping markers. To increase visibility, we included a larger marker representing five records of the same type, and avoided overlapping of other types by introducing an aggregate representation. We note that most of the records are located in a relatively narrow zone around the coast and along rivers, whereas the further inland regions are less densely covered. In particular, the Amazon forest region in northwestern Brazil has poor paleodata coverage in the four examined databases.

The Amazon region is particularly sensitive to changes in hydroclimatic conditions, and to better understand this sensitivity we need hydroclimate proxies. Tree rings can provide information on rainfall over the Amazon and its variability on the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (Brienen et al. 2012). In the Amazon, the El Niño phase leads to drought conditions which impacts the hydrological cycle across the basin (van Schaik et al. 2018). This can result in increased mortality, fires and reduction in photosynthetic capacity in the affected parts of the forest (Koren et al. 2018). Besides tree rings, speleothems can also provide constraints on hydroclimate and biodiversity in the Amazon basin (Cheng et al. 2013).

Remote sensing provides opportunities to study regions that are poorly covered by local measurements, and that are not easily accessible. Usually, remote sensing informs on current activities, but a notable exception is LiDAR technology, which has uncovered the location and extent of pre-Columbian settlements across the Amazon region. A recent study by Peripato et al. (2023) suggested that there are still many pre-Columbian earthworks to be found. Although one could argue that these measurements should also be considered paleorecords, we have not included them in our overview here.

We hope that this overview will be useful for researchers studying past climate in Brazil. Our analysis could inspire researchers to target locations for future research where there are currently gaps in data. We also encourage researchers who have already collected paleorecords in Brazil, but have not yet made their data available in one of the four major paleo data platforms, to do so. Further, we hope that this will support other initiatives such as the INQUA-funded pSESYNTH project that aims to increase data availability and discovery from the Global South, as reported by Kulkarni et al. (2023).

affiliationS

1Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University, Netherlands

2GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Germany

3American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA

contact

Gerbrand Koren: g.b.koren uu.nl

uu.nl

References

Brienen RJW et al. (2012) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 16957-16962

Cheng H et al. (2013) Nat Commun 4: 1411

Kaushal N et al. (2021) PAGES Mag 29: 50-51

Koren G et al. (2018) Phil Trans R Soc B 373: 20170408

Kulkarni C et al. (2023) PAGES Mag 31: 30-31

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2024

Past Global Changes Magazine

Muglia J.![]() 1, Mulitza S.

1, Mulitza S.![]() 2, Repschläger J.

2, Repschläger J.![]() 3 and Schmittner A.

3 and Schmittner A.![]() 4

4

The PAGES Data Stewardship Scholarship (DSS) contributed towards the completion of the first version of a database of carbon and oxygen isotopes from benthic foraminifera in deep-ocean sediment cores.

The Ocean Circulation and Carbon Cycling (OC3) working group (pastglobalchanges.org/science/wg/former/oc3) started in 2014. OC3 brought together researchers with a scientific question: What global changes can explain variations in ocean carbon and oxygen isotope ratios (δ13C and δ18O) in benthic foraminiferal samples from deep-sediment cores? Of particular interest was the transition between the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, 23–19 kyr BP) and early last deglaciation (19–15 kyr BP), where a first increase in atmospheric CO2 from glacial values (~180 ppm) is observed in ice-core data (Petit et al. 1999). δ13C from tests of benthic foraminifera in deep-ocean sediment cores is used in paleoceanography as a tracer for past deep-water mass structure (Curry and Oppo 2005). δ18O from the same samples is used as a tracer for deep-water temperatures and δ18O of sea water (Lynch-Stieglitz et al. 1999). Despite relatively large amounts of existing data, the use of stable isotopes in paleoclimate research is hindered by several issues, such as:

1) formatting differences among sites;

2) differences in the methodologies used to calculate age models and/or;

3) offsets due to different species used to measure stable isotopes, and species-specific corrections included in some data.

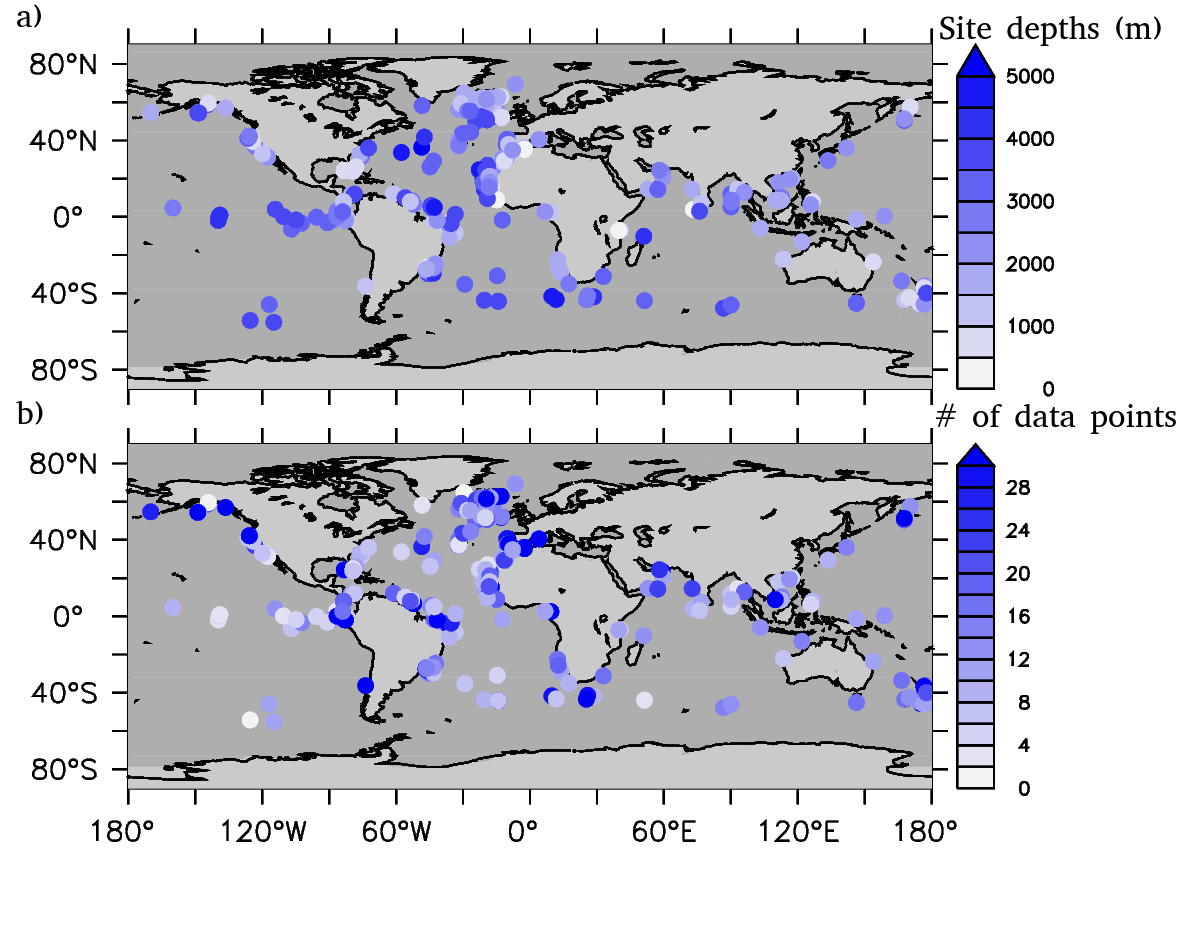

The OC3 community established standards to homogenize benthic foraminifera isotope data and age models from different sources. In 2021, OC3 was granted a DSS from PAGES, which enabled us to finish the database product in early 2023. The database is available at zenodo.org/records/1039126, and a description paper was published (Muglia et al. 2023). It includes 287 globally distributed coring sites (Fig. 1). A csv file format was chosen, which makes the files both machine- and human-readable. A quality check on the data and age models was performed before their inclusion in the database. To be able to resolve the rapid changes associated with the last deglaciation, we only include data with temporal resolution of 1 kyr or better (Fig. 1). Stable isotope data from the genus Cibicidoides were preferred. The choice minimizes offsets from contemporaneous δ13C of dissolved inorganic carbon in the overlaying bottom water. A toolbox written in Python calculates time slices, selects data by its time resolution, and plots data in time series, map, or vertical section formats. It is available in the database repository.

|

|

Figure 1: (A) Positions and depths (in m) of all sites included in our database. (B) Number of data points at each site in the 21–15 kyr BP time interval. Figure modified from Muglia et al. 2023. |

One important goal of OC3 is to quantify age-model uncertainties. For this purpose, we included different age models for sediment cores, if multiple age-model approaches were available. This enables an evaluation of the sensitivity of the reconstructed time evolution of benthic foraminiferal δ13C and δ18O, with respect to different age models. We found that offsets in time series of isotope ratios obtained from using different age models are typically smaller than the uncertainties in those age models. This suggests that the direction of changes in stable isotope ratios may be captured, irrespective of the age-model approach used. Due to its global coverage and high temporal resolution, the OC3 database allows scientists to reconstruct a four-dimensional picture of changes in δ13C and δ18O through the last deglaciation. The database is useful for modelers to compare with computer simulations of the deglacial state, and for paleoclimatologists to study past deep-ocean and carbon-cycle changes. The database structure can also be used as a template for compilations of other paleoceanographic data in the future.

Future plans

The OC3 database is an ongoing project, with updates and additions performed as new coring sites and age models are published in the literature, or provided by our collaborators. The database will be combined with visualization tools of PaleoDataView (marum.de/Dr.-stefan-mulitza/PaleoDataView.html). In addition, we plan to translate the database into formats compatible with the LinkedEarth initiative.

Benthic foraminifera δ13C and δ18O are useful, but limited, tracers for deep-ocean characteristics. Expanding the database with other paleo-tracers, such as radiocarbon ages, Pa/Th or Neodymium, will provide a more complete picture of the ocean in past-climate scenarios. For this reason, in a future project, the database will be expanded to include these tracers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to thank the immense and generous contributions from scientists around the world who have made the OC3 database possible.

affiliationS

1Centro para el Estudio de los Sistemas Marinos, CONICET, Puerto Madryn, Argentina

2MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, Germany

3Department of Climate Geochemistry, Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, Mainz, Germany

4College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, USA

contact

Juan Muglia: jmuglia cenpat-conicet.gob.ar

cenpat-conicet.gob.ar

REFERENCES

Curry WB, Oppo DW (2005) Paleoceanography 20(1): PA101

Lynch-Stieglitz J et al (1999) Nature 402(6762): 644-648

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2024

Past Global Changes Magazine

Thöle L.M.![]() 1, Kohfeld K.

1, Kohfeld K.![]() 2,3, Chase Z.

2,3, Chase Z.![]() 4, McKay N.

4, McKay N.![]() 5 and Crosta X.

5 and Crosta X.![]() 6

6

The PAGES Data Stewardship Scholarship program allowed us to compile and transform Southern Ocean sea-surface temperature data into the LiPD format, increasing the interoperability and, thus, facilitating analyses and comparisons.

Motivation

The C-SIDE working group (pastglobalchanges.org/c-side) has been diligently working towards unraveling the complexity of past Southern Ocean dynamics, with a specific focus on the role of Antarctic sea ice. Previous efforts, spearheaded by Chadwick et al. (2022), aimed to investigate the different patterns in sea-ice dynamics over the Last Glacial Cycle (130–12 ka). One of the primary objectives was the compilation of a comprehensive dataset on Antarctic sea ice, laying the groundwork for a deeper understanding of its dynamics in different regions on a glacial-interglacial timescale.

However, Antarctic sea ice, while a crucial component of Southern Ocean dynamics, is just one of many processes governing the region’s past oceanographic – and thus global climate – changes. Furthermore, the interplay of different processes remains unclear. Amongst these processes, sea-surface temperature (SST) dynamics seem to be the obvious first candidate to strongly influence sea ice, and vice versa.

Recognizing the need for a holistic approach, we sought to provide insights into circumpolar Southern Ocean SST changes. To achieve this, we meticulously compiled previously published SST data, positioning our project within a broader context of Southern Ocean dynamics. By undertaking this comprehensive analysis, we aimed to uncover not only the isolated impacts of SST, but also its potential co-dependencies with other factors, foremost sea-ice dynamics.

Southern Ocean SST data compilation and LiPD format standardization

The initial phase of our project involved the compilation of previously published SST data. Here, our focus lay on expanding on efforts by Kohfeld and Chase (2017), mostly adding later datasets. We considered datasets of all resolutions and proxies that cover the Last Glacial Cycle. In the future, the inclusion of certain proxies might be under debate if results point to a misuse of that proxy as an SST proxy.

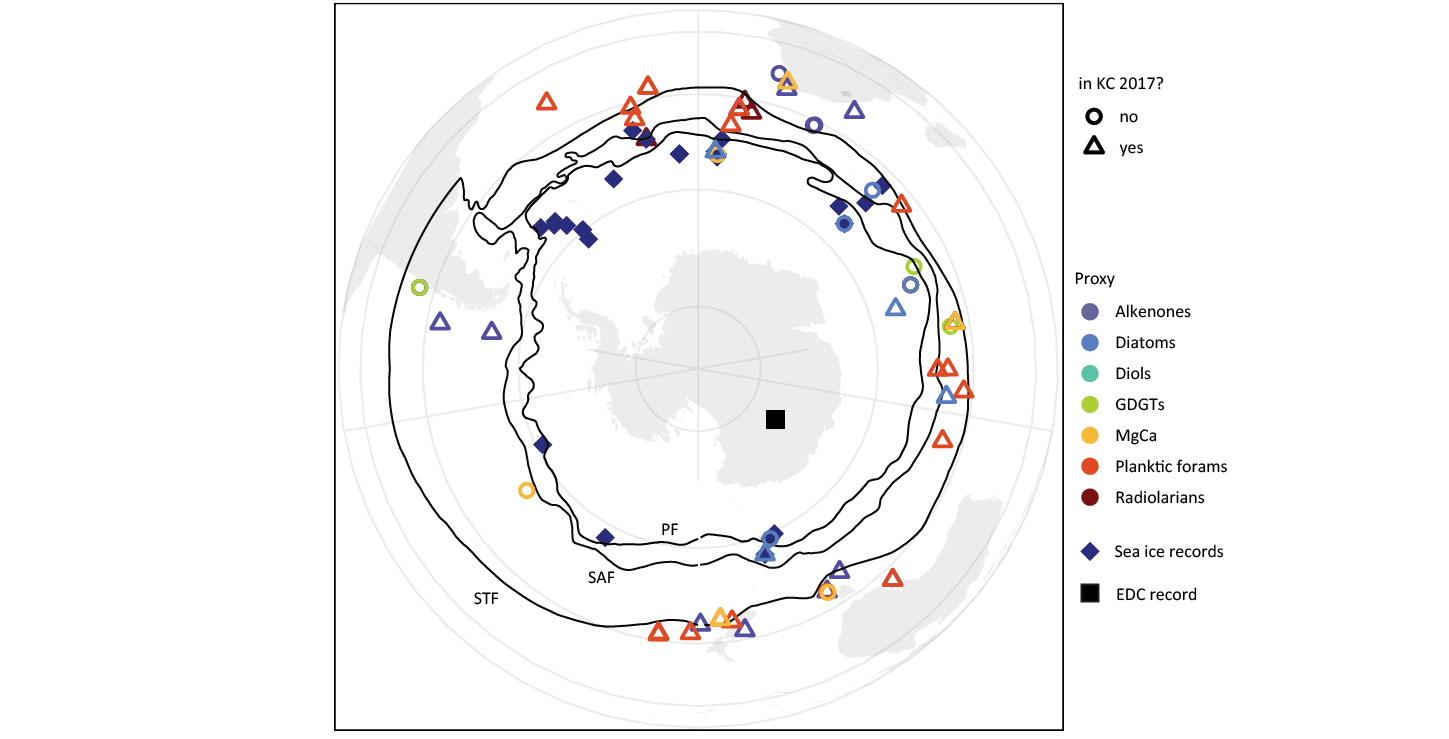

A first main outcome from the compilation is the distribution of cores, and the scarcity of cores and data for certain regions and zones (Fig. 1). The low number of records from the Antarctic Zone limits the possibilities of investigating connections to sea ice, as well as calculating basin-spanning SST gradients. Furthermore, the Pacific basin is strongly underrepresented, limiting the significance of general findings.

|

|

Figure 1: Overview map of compiled SST proxy data for the Last Glacial Cycle. KC 2017: Kohfeld and Chase (2017). |

To enhance interoperability and facilitate the seamless reuse of our data compilation, we adopted the LiPD format (McKay and Emile-Geay 2016). This decision was underpinned by the LiPD format’s provision of standardized metadata and vocabulary, streamlining the process of data interoperability and reusability for fellow researchers. The LiPD format not only aligns with best practices in data management, but also reflects our commitment to contributing to a collaborative and interconnected (paleo)research environment.

One of the most challenging aspects we encountered was reconciling variations in age models and proxy calibrations across and within different datasets. Addressing these discrepancies proved very challenging due to limited documentation on changes, reasoning and references to previous data. Similarly, retracing these steps and recalibrating both age-model constructions and proxy calibration was hindered by the sparse documentation and availability of raw data. With the compiled and standardized dataset at our disposal, we could start analyzing the patterns and dynamics of past SST in different basins and zones of the Southern Ocean for the Last Glacial Cycle.

Current and future plans

The C-SIDE Southern Ocean SST data compilation, together with our analyses scripts (in R), will be made available on PANGAEA and the LiPDverse website (lipdverse.org). A future project, granted by the Dutch Research Council (NWO), will aim to expand this database and include other proxy data for the Southern Ocean. This will further enhance the interoperability of past Southern Ocean data, and facilitate disentangling different processes driving CO2 storage and release, and comparison to models. Our team is preparing a manuscript describing the data compilation, analyses and new results emerging from this SST overview for the Southern Ocean.

DISCLAIMER

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used ChatGPT 3.5 in order to try out its usefulness. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

affiliationS

1Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Netherlands

2Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia

3The Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS), University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia

4School of Earth and Sustainability, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, USA

5University of Bordeaux, CNRS, Bordeaux INP, EPOC, UMR 5805, Pessac, France

6School of Resource and Environmental Management and School of Environmental Science, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada

contact

Lena Thöle: l.m.thole uu.nl

uu.nl

REFERENCES

Chadwick M et al. (2022) Clim Past 8(18): 1815-1829

Kohfeld KE, Chase Z (2017) Earth Planet Sci Lett 472: 206-215

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2024

Past Global Changes Magazine

Atwood A.R.![]() 1, Moore A.L.

1, Moore A.L.![]() 1, Long S.

1, Long S.![]() 1, Pauly R.1, DeLong K.

1, Pauly R.1, DeLong K.![]() 2, Wagner A.

2, Wagner A.![]() 3 and Hargreaves J.A.

3 and Hargreaves J.A. ![]() 4

4

The PAGES Data Stewardship Scholarship contributed to the development of an updated metadata-rich database of seawater δ18O data by the CoralHydro2k Network.

The oxygen isotopic composition (δ18O) of seawater is a powerful tracer of the global water cycle, providing valuable information on the exchange of water between the ocean, atmosphere and cryosphere, as well as on ocean-mixing processes (LeGrande and Schmidt 2006). As such, these data provide an additional degree of freedom for understanding the complex hydroclimate system, beyond what standard oceanographic variables like temperature and salinity can offer. The integration of water isotopes into climate models has also made them an important diagnostic for assessing model performance and skill. Furthermore, because seawater isotopes form the basis of paleoclimate proxies based on the δ18O of marine carbonates, they provide a "common currency" that links paleoclimate reconstructions, modern climate observations and isotope-enabled model simulations, allowing hydrological processes to be evaluated on a wide range of time and spatial scales (Dee et al. 2023).

In recognition of the broad value of seawater δ18O data, and the growing number of seawater δ18O datasets that have been generated over the last decade, the CoralHydro2k Seawater δ18O Database project (pastglobalchanges.org/science/wg/2k-network/projects/coral-hydro/intro) was launched in 2020 to recover "hidden" seawater oxygen-isotope data that were not easily findable. Over the past three years, we have integrated these records with data from public databases and repositories to create a new, centralized, machine-readable, and metadata-rich database that aligns with findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR) standards.

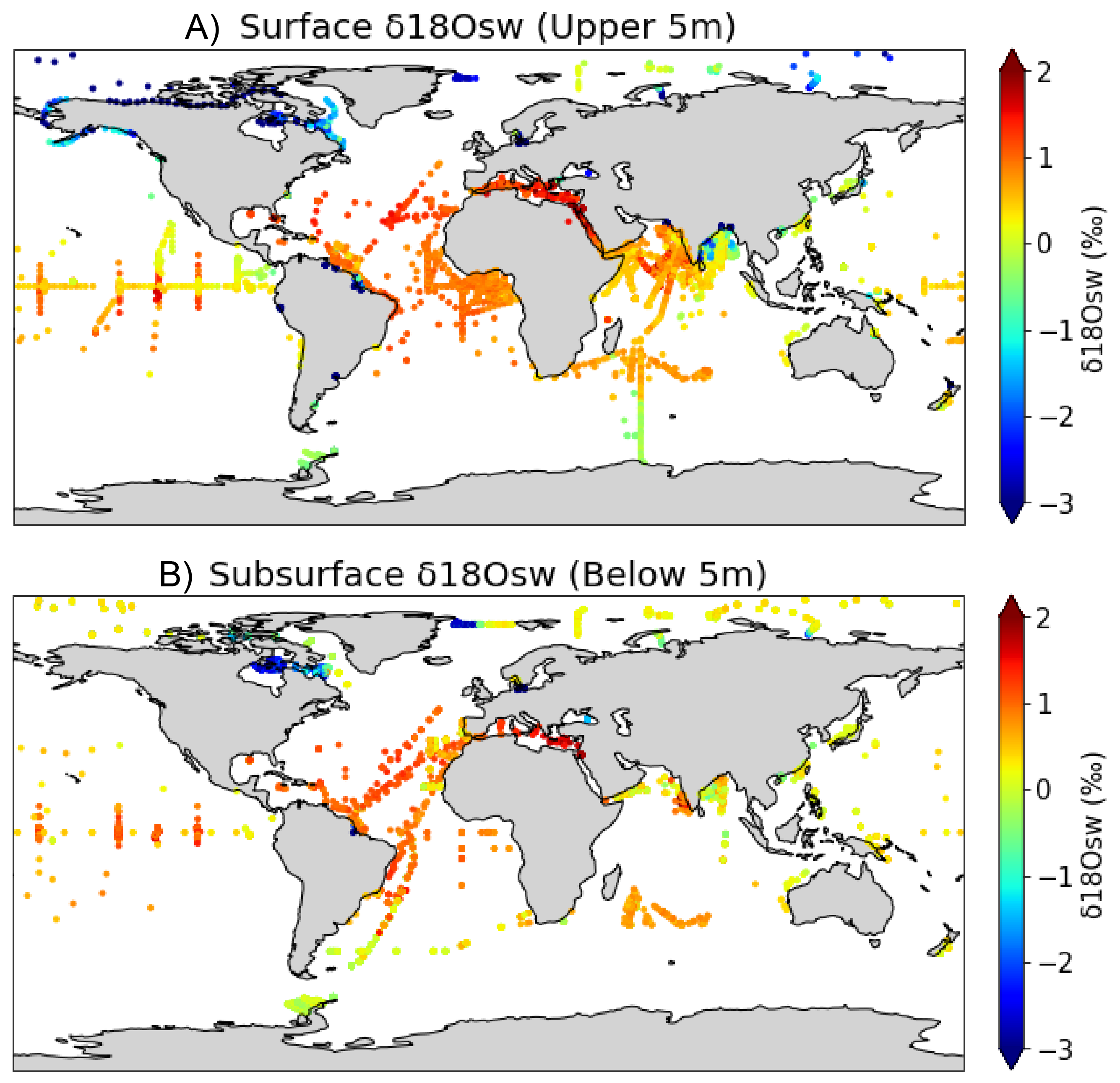

Database overview

The new database consists of 18,615 seawater δ18O observations from 107 datasets. O these data, 53% were not previously available in public databases or data repositories. These "hidden" data were recovered via direct author submission (39%), scientific papers (12%) and theses/dissertations (2%). The other 47% of the data were gathered from public databases and repositories, with the largest contributions from the GEOTRACES 2021 Intermediate Data Product (13%; Schlitzer et al. 2021), the NASA GISS Global Seawater Oxygen-18 Database (10%; Schmidt et al. 1999), PANGAEA (7%), CISE-LOCEAN Seawater Isotopic Database (7%; Reverdin et al. 2022), and GLODAPv2 (3%; Key et al. 2015; Olsen et al. 2016). When recovering "hidden" data, we collected data from all regions and all depths of the global ocean. Our public data curation efforts were focused on the upper 50 m from 35°N to 35°S to align with the goals of CoralHydro2k (Fig. 1).

|

|

Figure 1: Seawater δ18O measurements from (A) the surface ocean (upper 5 meters of the water column) and (B) the subsurface ocean (below 5 meters of the water column). |

The extensive metadata is a unique aspect of the database. Only eight metadata fields are required, but an additional 44 optional metadata fields provide important supporting information, including isotope-analysis technique, sample collection and storage notes, site information, paired salinity, temperature, and seawater δ2H values. This template provides a set of best practices for reporting seawater isotope data.

EarthChem community for dataset DOIs

A second achievement of the project was the development of a Seawater Oxygen Isotopes Community within the EarthChem Library, an open-access repository for geochemical datasets (earthchem.org/communities/seawater-oxygen-isotopes), where researchers can submit their seawater isotope data and obtain a dataset DOI. We hope that the creation of this site helps researchers publish their seawater isotope datasets, minimizing the number of "hidden" datasets. The template provided on the EarthChem Seawater Oxygen Isotopes community webpage is aligned with the CoralHydro2k Seawater δ18O Database to facilitate future updates to the database.

Current and future plans

We are currently preparing a database description paper. Once published (expected in 2024), the CoralHydro2k Seawater δ18O Database will be available in the NOAA/World Data Service for Paleoclimatology archives: ncei.noaa.gov/access/paleo-search/study/35453, with additional data visualization features provided through waterisotopes.org.

This database represents an important step towards increasing the availability and usability of seawater isotope data. As future investments in water isotope observation networks become available, this data will be well-suited to tackle 21st-century research questions related to ocean changes in the past, present and future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many additional CoralHydro2k project members contributed to this database, including Emilie Dassié, Antje Voelker, Chandler Morris, Erika Ornouski, Kim Cobb, and Thomas Felis. We thank Gilles Reverdin for useful discussions about the database, and we gratefully acknowledge the many researchers and funding agencies responsible for the collection, quality control and publication of the seawater isotope data.

affiliationS

1Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science Department, Florida State University, Tallahassee, USA

2Department of Geography and Anthropology and Coastal Studies Institute, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, USA

3Department of Geology, California State University, Sacramento, USA

4MARUM – Centre for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, Germany

contact

Alyssa R. Atwood: aatwood fsu.edu

fsu.edu

references

Dee S et al. (2023) Environ Res: Climate 2: 022002

LeGrande AN, Schmidt GA (2006) Geophys Res Lett 33: L12604

Olsen A et al. (2016) Earth Syst Sci Data 8: 297-323

Reverdin G et al. (2022) Earth Syst Sci Data 14: 2721-2735

Schlitzer R et al. (2021) The GEOTRACES Intermediate Data Product 2021.

Schmidt GA et al. (1999) Global Seawater Oxygen-18 Database - v1.22

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2024

Past Global Changes Magazine

Palmer A.P.![]() 1, Beckett A.

1, Beckett A.![]() 1, Brauser A.2, Blanchet C.

1, Brauser A.2, Blanchet C. ![]() 2, Martin-Puertas C.

2, Martin-Puertas C.![]() 1, Ramisch A.3 and Brauer A.2

1, Ramisch A.3 and Brauer A.2

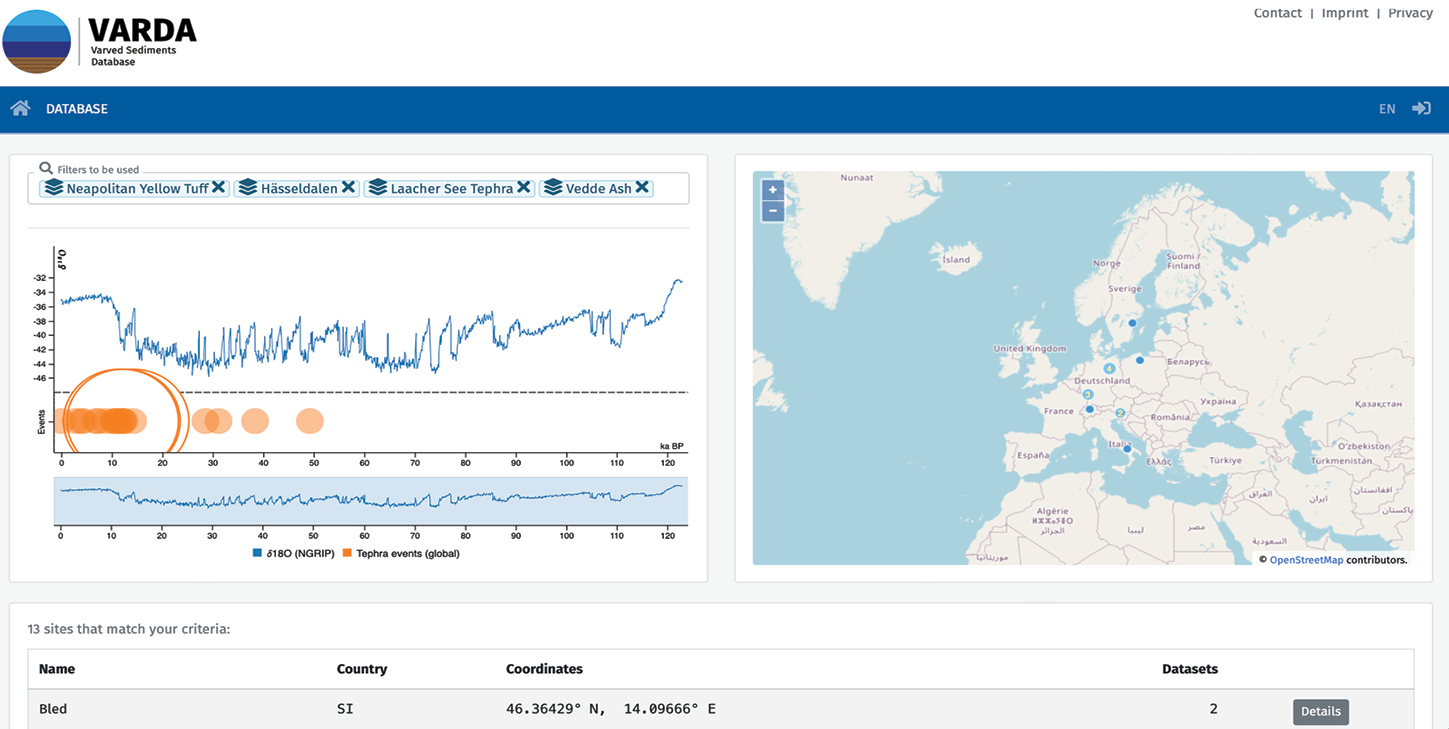

The PAGES Data Stewardship Scholarship has added new tephra datasets to VARDA, an online global database of varve records, to enhance high-resolution chronology construction.

Annually laminated (varved) sediments are recovered from lakes and ocean basins in different climatic settings and provide the opportunity to examine past environmental and climatic changes at the highest possible temporal resolution, comparable to tree-ring and ice-core chronologies. The Varved Sediments Database (VARDA) was built to explore the spatial and temporal distribution of terrestrial varved archives (Ramisch et al. 2020). VARDA includes information on the location of varved sites, the duration of the varve record and available proxy datasets, and is openly accessible at varve.gfz-potsdam.de. In addition to varve counting, the database contains radiometric dating measurements (e.g. 14C) that enable varve chronologies to be anchored to an absolute timescale.

An important milestone in the development of VARDA is the inclusion of tie-points that can help link spatially distant archives to understand the spatio-temporal complexity of abrupt climate change. Indeed, the combination of accurate dating, solid tie-points and annually resolved archives would be a step-change to detemine the regional environmental variability during climatic transitions, and leads or lags between forcing and responses.

|

|

Figure 1: The VARDA interface with an example of four tephra horizons selected in the filter function, with lake sites in Western Europe that contain those records. |

The purpose of the PAGES Data Stewardship Scholarship (DSS) was, therefore, to review and incorporate volcanic-ash (tephra) layers identified in varved-lake sequences in VARDA. Tephras are airborne, near-instantaneous deposits that spread over large regions, and can be distinguished by their specific mineralogical and chemical composition. In the last two decades, there has been an increase in the use of non-visible (crypto-)tephra layers within lake-sediment sequences that greatly densified the tephra framework. Also, the correct attribution of a tephra layer to a volcanic-source area, and a specific eruption of a known age, requires measurement of the geochemical composition of individual tephra shards, generating a wealth of new data. We therefore aimed to collect and incorporate recent tephra findings in varved sediments to VARDA, including their geochemical datasets. We first focused on the last deglaciation time period, i.e. between 25–8 kyr BP.

The scholarship initially had a European focus and explored the varve-lake records with tephra horizons from both VARDA and new published datasets. This information was used to decide how the metadata would be presented and accessed within the database, and to identify the mandatory/optional datasets. From 33 lakes in Europe, 22 contained tephra layers and 19 have associated geochemical datasets updated into VARDA. In total, there are 49 discrete, known tephra layers within the time period with volcanic sources from Iceland, Eifel, Massif Central, Hellenic Arc and Italy across these sites. There are 19 tephra horizons represented at more than one site that will enable more precise synchronization and comparisons between the varve records. On the VARDA landing page, it is now possible to search with different filters for ‘varves’, ‘tephra’ and ‘tephra chemistry’, examining the map for those sites with tephra, and accessing the geochemistry datasets. The geochemical data also includes metadata related to the analytical procedure followed, such as the instrument and secondary standards used. Further information on the European datasets are provided in Beckett et al. (2024), who identify key outcomes from this work as: i) a single repository for tephra geochemical data within varve records, ii) better understanding of the time periods with multiple eruptions, iii) the spatial distribution of the key eruptions, and iv) the potential for new varved sites to contain specifIc tephra horizons.

This work is moving toward the final completion of the DSS by extending the tephra geochemistry information in a spatial and temporal context. Identification of an additional 32 lake records beyond Europe, and extending the time window to between 125 kyr and the present day, will expand the scope of the database and explore the potential regional and hemispheric interconnectivity of the varve records when linked using tephra horizons. The Varve Database will not only benefit the paleolimnological and lake research communities, but also aid other disciplines when trying to establish links between marine and terrestrial systems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

GFZ for hosting the database. Konstantin Mittelbach for database administration, Rebecca Kearney and Ian Matthews for oversight of tephra components of the project.

affiliationS

1Department of Geography, Royal Holloway, University of London, UK

2GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Helmholtz Centre Potsdam, Germany

3Department of Geology, University of Innsbruck, Austria

contact

Adrian P. Palmer: a.palmer rhul.ac.uk

rhul.ac.uk

references

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2024

Past Global Changes Magazine

Boyle J.F.1, Moyle M.1 and Dubois N.2

3rd Human Traces Pb records project workshop, Liverpool, UK, and online, 20–21 September 2023

The Human Traces (pastglobalchanges.org/human-traces) working group (WG) focuses on the long legacy of pre-Anthropocene human impacts, and how they manifest themselves in different parts of the world and in different types of stratigraphic records. The activities of the WG aim to address the knowledge gap concerning spatial and temporal variations in early human impacts on ecosystems, with the overarching goal to create a global synthesis of human traces in geologic archives. Following a presentation on Greenland ice-core Pb records by Professor Joe McConnell at an earlier Human Traces workshop (see McConnell et al. 2018), a discussion identified the need to link environmental archives more fully to address some specific questions about regionality of long-transported atmospheric Pb pollution. A Pb records sub-group was established with the aims of: 1) assembling long (Holocene) lake and peat sediment Pb records from around the world, for comparison with these high-resolution ice-core records, and to produce a database that will be of wider use to the paleocommunity, and 2) reviewing methodological approaches to collecting Pb sediment records.

A hybrid workshop was held on 20–21 September 2023 at the Department of Geography & Planning, University of Liverpool. Twelve individuals attended in person, with a further seven online. The primary aims of the workshop were to: 1) review records assembled by the participants, and choose regions for a global synthesis paper; 2) identify: data gaps, common narratives, significant periods and their spatial footprints, and factors influencing Pb distribution, and 3) develop papers on methodologies and grand challenges.

Global synthesis paper

Having identified a number of existing and potential long Pb records in peat and lake sediment archives across the globe (Fig. 1a), we discussed approaches to identifying regions for a global synthesis paper. We concluded that the two ideal approaches of identifying regions based on 1) statistical analysis of pattern, or 2) analysis of metallurgical historical/archaeology, were impractical. The former lacks sufficient data points, and the latter is of a complexity beyond the scope of a single paper. Instead, we agreed on regions based on the collective experience of the workshop participants (Fig. 1b). These regions were not given strict definitions, and we have subsequently decided to use the IPCC region polygons, slightly modified to meet our needs by some splitting and merging.

|

|

Figure 1: (A) Long Pb records in peat and lake sediment identified at the workshop. (B) Provisional regions for global synthesis. |

The records identified at the meeting (N=192) clearly do not include all existing datasets. We continue to add sites as we find them and welcome suggestions. We have deliberately included regions that contain no sites. For these we can predict what patterns are expected, and can predict areas where suitable sites may occur. Each region in the global synthesis will receive just one page of figures and text. The figures will show a small number of sites, selected to be representative of the regions, and the text will offer a chronological account of the major features of the records, with reference to known historical and archaeological narratives. A short global summary will compare and contrast the regions, identifying major trends, information gaps and new research questions.

Methodological issues

A productive discussion was held about methodological issues such as appropriate analytical techniques (is scanning XRF sufficiently precise?), source identification by isotopes or by enrichment factors, whether fluxes or concertation data should be preferred, and approaches to variable chronological confidence. We concluded that the body of published records could have been more usefully combined had there been some agreed community standards in methodology and reporting. In response, we have decided to write a methods paper aimed at research students and early-career researchers (ECRs), and cover the full process from site selection, choice of methods, data processing, and reporting standards, and have sketched out a plan for this paper.

Other outputs

The initial objective of the WG was to generate a community database of long Pb records (to be hosted by Neotoma), with an associated published description and analysis of the records found. This remains the primary planned output. The "Global Synthesis" and the "Methods" papers described above will supplement this work and provide a contribution to the wider research community of exceptional value. In addition to this, we recognize that a number of research pathways may arise from the new dataset. To reflect this, we decided to write a "Grand Challenges" paper, covering topics such as: distinguishing the impacts of historical empires on the ancient global Pb pollution signal; distinguishing mining from metallurgical signals; and separating the signal of Pb due to silver mining from later direct Pb mining.

affiliationS

1Department of Geography & Planning, University of Liverpool, UK

2EAWAG – Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland

contact

John F. Boyle: jfb liverpool.ac.uk

liverpool.ac.uk

references

McConnell JR et al. (2018) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: 5726-5731

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2024

Past Global Changes Magazine

Hamilton D.S.1, Perron M.M.G.2, Llort J.3, Hebden S.4 and Morrill M.H.5

FLARE workshop, Bermuda, and online, 18–21 September 2023

Fire is a key component of the Earth System, modified by, and impacting on, human activities. It shapes and regulates terrestrial ecosystems (Pausas and Bond 2020), but also drives changes in weather, climate (Hamilton et al. 2018), carbon (Lasslop et al. 2019), and nutrient cycling (Perron et al. 2022) through the many complex interactions of fire and its emissions in the Earth System. From land to ocean, from vegetation to human society, and from the past to the future; fire is a truly transdisciplinary research topic.

Although fire is an integrated component of the Earth System, integrated research across disciplines, institutions and fire practitioners is currently lacking. As a result, it is difficult to obtain the much-needed holistic understanding of how rapid changes in wildfire activity will impact ecosystems and society in the coming decades.

Diverse expertise from across the geosciences and social sciences is needed to fully appreciate and identify the main challenges in fire science. The changing trends in fire intensity and its spatial reorganization, in response to climate change, are altering the interactions between fire and other components of the Earth System, including society (Kala 2023). This clearly signals an urge for better communication between scientific, societal, stakeholder, and government representatives.

To address this need, the ambition of the FLARE (Fire science Learning AcRoss the Earth system) workshop was to gather a transdisciplinary international panel of researchers and fire practitioners. Participants discussed the challenges in understanding fire behavior and its impacts across the world and over varied timeframes, the tools that we have, and the need to address these challenges, as well as how to better communicate across disciplines. The goal is to synthesize this knowledge and formulate a roadmap for more integrated wildfire research over the next five to 10 years.

Held from 18–21 September 2023, FLARE gathered experts from disciplines across the Future Earth global research network. Expertise in physical and social science, remote sensing, fire communicators and artists, operational fire scientists, and fire managers were all present. Participants represented 14 countries, and both early-career and gender equity were achieved overall. The workshop was held in a hybrid format, with 15 onsite participants invited to meet at the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences (BIOS, bios.asu.edu) and 22 participants online. The four-day workshop included lightning presentations from each participant, 20 keynote talks, lively discussions, and four in-depth breakout sessions.

The workshop highlighted a poor constraint on "impacts of fires on the Earth System" which stem from a lack of communication between relevant fields of expertise. In particular, a disconnection was identified between the scientific aspect of fire and the societal implications of fire events. Workshop participants identified three main challenges that need to be addressed by the global fire community:

(Challenge 1) Unifying transdisciplinary research around common boundary objects, starting with "Fire’s role in the carbon cycle";

(Challenge 2) Better characterizing "Fire and extreme events";

(Challenge 3) Taking a holistic approach to understanding "Fire interactions with humans".

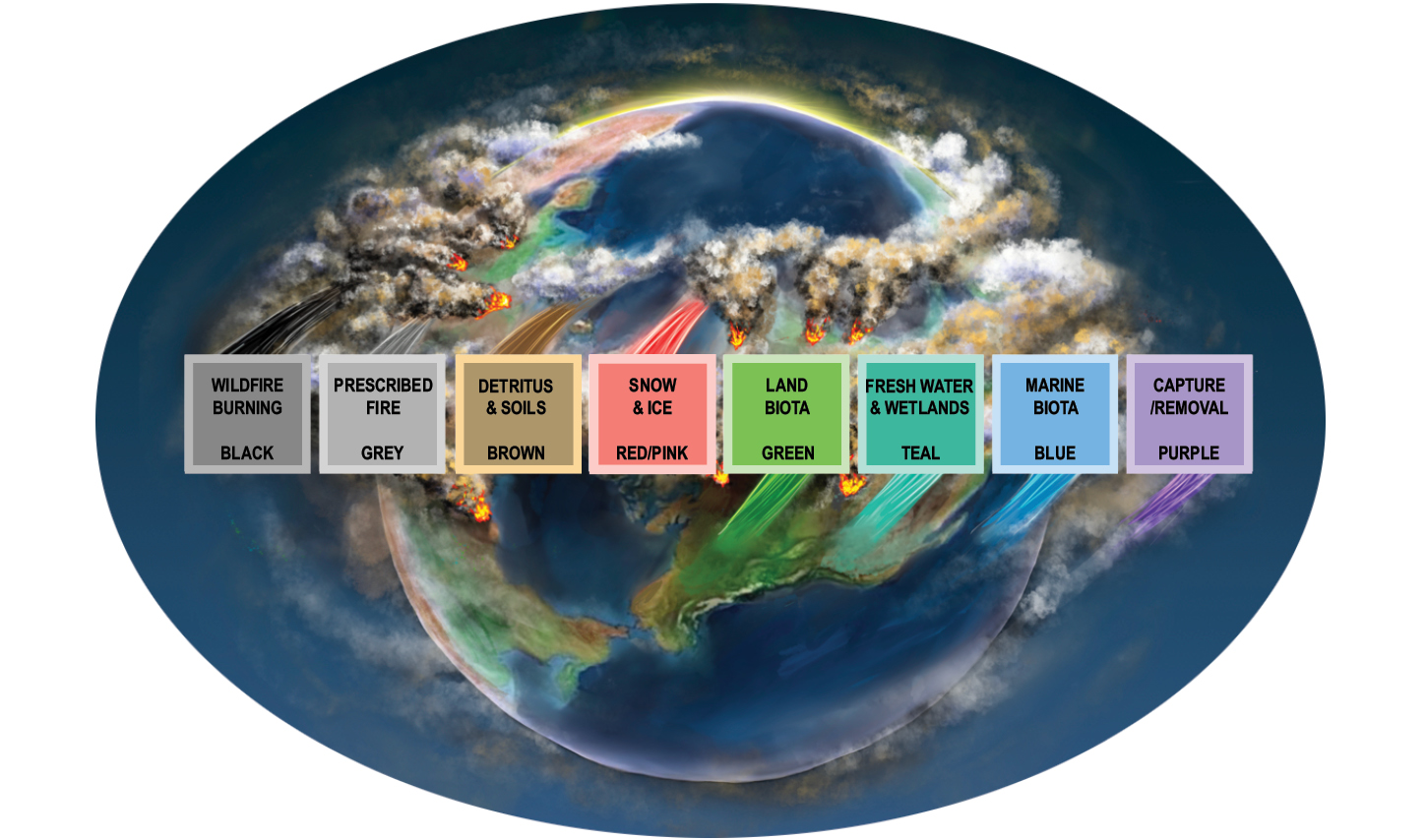

The FLARE workshop also included an onsite public engagement event organized by the US Consul General Office of Bermuda. Dr Ben Poulter (NASA) visited students at the Warwick Academy to discuss NASA’s role in Earth science, climate change and blue carbon ecosystems. Additionally, fire-science illustrators Miriam Morrill and Jessie Thoreson captured the transdisciplinary collaboration process during the workshop, characterizing the carbon cycle as a potential boundary object for collaborative global fire science connectivity (Fig. 1).

|

|

Figure 1: An eye on fire’s role in the carbon color spectrum. Upward pointing box "tails" indicate carbon sources, and downward pointing box "tails" indicate carbon sinks. |

Ongoing work now addresses the identified challenges, and during 2024 a roadmap for coordinated wildfire research, in the form of a white paper, will be produced. As part of the white paper, FLARE plans to include a dedicated early-career researcher perspective on the workshop and its outcomes, as well as recommendations for inclusive fire science across different communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FLARE received funding from ESA and Future Earth via their Joint Program (futureearth.org/initiatives/funding-initiatives/esa-partnership), PAGES, North Carolina State University (Hamilton’s start-up), and BIOS (bios.asu.edu).

affiliationS

1Carrera de Biología Marina, Universidad Científica del Sur, Lima, Perú

2Programa Doctoral en Recursos Hídricos, Universidad Nacional Agraria la Molina, Lima, Perú

3Dirección de Asuntos Antárticos, Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, Lima, Perú

4Centro Universitario Regional Este, Universidad de la República, Rocha, Uruguay

5Instituto de Oceanografia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande, Brazil

contact

Douglas S. Hamilton: dshamil3 ncsu.edu

ncsu.edu

references

Hamilton DS et al. (2018) Nat Comms 9: 3182

Kala CP (2023) Nat Hazards Res 3: 286-294

Lasslop G et al. (2019) Curr Clim Change Rep 5: 112-123

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2024

Past Global Changes Magazine

Bouchet M.![]() 1, Donner A.2, Grimmer M.3, Jasper C.4, Krauss F.3, Legrain E.5 and Vera Polo P.

1, Donner A.2, Grimmer M.3, Jasper C.4, Krauss F.3, Legrain E.5 and Vera Polo P.![]() 6,7

6,7

Final QUIGS workshop, Grenoble, France, and online, 19–22 September 2023

Eleven interglacials have been identified in the past 800 kyr (Past Interglacials Working Group of PAGES 2016). Around 430 kyr BP, a change in interglacial strength, known as the Mid-Brunhes Event (MBE), was observed in atmospheric CO2 levels, and in proxy records of Antarctic and global surface temperatures, marking a transition to stronger interglacials, such as Marine Isotope Stages (MISs) 5e and 11c (Fig. 1). While the onset of interglacials seems linked to an increased Northern Hemisphere summer insolation, uncertainties persist due to complex interactions involving astronomical forcing, ice volume, CO2 levels, and temperature.

Active research areas in Late Pleistocene interglacials focus on those not aligning with the astronomical theory of ice ages, and on long-term changes in interglacial intensity over the past 800 kyr. To address these topics, the PAGES working group on Quaternary Interglacials (QUIGS) convened in Grenoble, France. Here we highlight some of the topics covered, and a few of the presentations that led to particular areas of discussion.

The unusual MIS 11c interglacial is known for its prolonged high sea-level and atmospheric CO2 concentrations, despite weak summer-insolation forcing (Tzedakis et al. 2022). The prolonged Termination V was suggested to be associated with the largest sea-level contribution from the Greenland Ice Sheet over the last 800 kyr. Alessio Rovere showed how large ice sheets may drive high sea-level stands, with MIS 12 believed to have featured one of the most extensive glaciations (Batchelor et al. 2019). Claire Jasper’s study of iceberg rafted debris (IRD) in the Southern Ocean’s Atlantic sector, during Termination V and MIS 11c, indicated a protracted period of Antarctic Ice Sheet iceberg discharge and melt. Steve Barker suggested that the asynchronous phasing of obliquity and precession during Termination V (Fig. 1) may explain the prolonged nature of this deglaciation.

The necessity to develop a coordinated modeling protocol over the Termination V-MIS 11c time period was discussed. In this framework, the group agreed on the importance of constraining the volume and extent of the MIS 12 ice sheet, and developing a coherent temporal framework for the rate of sea-level rise, and for various paleoclimate proxies representative of different parts of the Earth System across the deglaciation.

The second part of the discussions delved into the MBE, addressing challenges related to the metrics of interglacial intensity. Mean Ocean Temperature reconstructed by Markus Grimmer emerged as a potential metric for distinguishing between strong and weak interglacials. A debate arose regarding the classification of early interglacial peaks in CO2, known as overshoots, and whether they are part of the interglacial or termination. Takahito Mitsui presented a model predicting interglacial intensity based on the previous glacial strength and summer insolation, received at both northern and southern high latitudes during deglaciation. According to Mitsui et al. (2022), the increase in interglacial intensities after the MBE is related to the amplitude increase in obliquity cycles. Finally, Quizhen Yin pointed out that in some records, such as Chinese loess, there is no discernable increase in interglacial strength across MBE. This observation gave rise to the alternative suggestion: can we use records where MBE is not detectable to understand what causes the observation of MBE in other records? In conclusion, an outline for a short position paper effort was defined on our current knowledge of interglacial intensity, incorporating both paleoclimate records and modeling.

The QUIGS leadership team thanks all the participants who engaged in this final workshop, and throughout the QUIGS adventure, extending thanks to PAGES for their continuous support.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank PAGES, the LABEX-OSUG and the AXA Research Fund for financially supporting the last QUIGS workshop.

affiliationS

1Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement, LSCE-IPSL, CEA-CNRS-UVSQ, Univ. Paris-Saclay, Gif-sur-Yvette, France

2Institute of Geology, University of Innsbruck, Austria

3Climate and Environmental Physics and Oeschger Center for Climate Research, University of Bern, Switzerland

4Columbia University, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Palisades, NY, USA

5University of Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, INRAE, IRD, Grenoble INP, IGE, Grenoble, France

6Dipartimento di Biologia Ambientale, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

7Departamento de Estratigrafía y Palentología, University of Granada, Spain

contact

Marie Bouchet: marie.bouchet lsce.ipsl.fr

lsce.ipsl.fr

REFERENCES

Batchelor CL et al. (2019) Nat Commun 10: 3713

Bouchet M et al. (2023) Clim Past 19: 2257-2286

Donders T et al. (2021) Proc Natl Acad Sci 118: e2026111118

Mitsui T et al. (2022) Clim Past 18: 1983-1996

Past Interglacials Working Group of PAGES (2016) Rev Geophys 54: 162-219

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2024

Past Global Changes Magazine

Hibberts A.![]() 1 and Huhtamaa H.

1 and Huhtamaa H.![]() 2,3

2,3

Climate in History: Summer school for early-career researchers, Aeschi bei Spiez, Switzerland, 16–20 August 2023

Historians have much to contribute to paleosciences, especially to the study of past climatic changes. Written records, for example, offer invaluable climate data, allowing high-resolution reconstructions. Similarly, the interaction between humans and past environments can help us better understand the complexity of climate-society entanglements on various temporal scales – ranging from rapid environmental degradation to multi-centennial dynamics of societal adaptation and resilience.

However, few historians conduct research on, or teach about, past climatic changes. At the same time, the next generation of historians have expressed a growing interest in incorporating the study of climate into their examination of the past.

The Climate in History summer school, held in Aeschi bei Spiez near the Lake of Thun, Switzerland, provided a vital opportunity to redress this imbalance. The summer school gathered a cohort of PhD and early-postdoctoral researchers for four days of talks, seminar discussions, activities and group work. The keynote talks and related exercises were led by international experts, including members the PAGES 2k Network, VICS, and CRIAS working groups. In addition, Patrick Cho welcomed the next generation of climate historians to join the PAGES Early-Career Network (ECN).

Building the basics

Stefan Brönnimann opened the summer school with a crash course on climatology. His keynote took us on a whistle-stop tour of the fundamentals of weather, climate and global patterns of change over time. Further talks explored different climate proxy data types. Andrea Seim introduced the use of tree rings to detect past temperature and precipitation variability, while Michael Sigl demonstrated how scientists detect volcanic signals from ice-core evidence.

The second day brought additional methodological discussions. Elena Xoplaki introduced further climatological basics and demonstrated how paleomodeling can help historical research. Sam White explained the utility of indexing historical documentary data — from the archives of societies — for past climate reconstructions (Camenisch et al. 2022). Elaine Lin’s REACHES database, a collection of written weather records from China for the last 3000 years, was introduced as an exemplar (Wang et al. 2018). Christian Rohr, who discussed what climatic information pictorial sources might contain, delivered the last keynote talk.

Each keynote talk was followed by exercises making use of the methodology or source base discussed, suggesting a pedagogical approach attendees could transfer back to their own institutions. All speakers compellingly communicated how accessing climate data can generate new narratives of the past.

The Skippon diary

The main segment of the summer school centered around applying newly learned techniques to an exciting primary source: a weather diary produced by Sir Philip Skippon, a Suffolk gentleman, between 1673 and 1674 CE.

Attendees were divided into groups to transcribe and interpret different chronological sections. The data was subsequently compared to other material, including state-of-the-art reanalyses, weather diaries from northern England and instrumental observations recorded in Paris. These suggested the Skippon diary was a relatively reliable indicator of weather patterns.

Final reflections

The summer school provided a rare, but essential, opportunity for humanities-based historians to acquire training in methods drawn from the climate sciences. Crossing firmly fixed disciplinary boundaries was not easy and demanded patience and perseverance from all participants, many of whom had never been trained in quantitative data analysis.

However, the value of interdisciplinary collaboration was made clear when historians brought their skills in source criticism to bear on the use of historical documents in past climate reconstruction. Not all sources are reliable and must be judged in a cultural context to extract meaning. Acknowledging this enables historical data to be used more sensitively, and with better results, when reconstructing past climatic change and its impacts on human society.

Teaching and learning across disciplines may be what is needed to drive "positive change" in higher education, and foster a deeper constructive critique of our current climate crisis and necessary responses (McCowan 2023). Historians can, and should, be an important part of this conversation. As Andrea Seim succinctly argued at the summer school: "The past is the key to the future."

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all participants and keynote lecturers for an amazing experience. In addition, we are grateful for support from PAGES, Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 218829), European Society for Environmental History, and the Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research (University of Bern).

affiliationS

1Department of History, University of Durham, UK

2Institute of History, University of Bern, Switzerland

3Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research, University of Bern, Switzerland

contact

Heli Huhtamaa: heli.huhtamaa unibe.ch

unibe.ch

references

Camenisch C et al. (2022) Clim Past 18 (1): 2449-2462