- Home

- Publications

- PAGES Magazine

- Data Constraints On Ocean-carbon Cycle Feedbacks At The Mid-Pleistocene Transition

Data constraints on ocean-carbon cycle feedbacks at the mid-Pleistocene transition

Farmer JR, Goldstein SL, Haynes LL, Hönisch B, Kim J, Pena L, Jaume-Seguí M & Yehudai M

Past Global Changes Magazine

27(2)

62-63

2019

Jesse R. Farmer1,2, S.L. Goldstein3,4, L.L. Haynes3,4, B. Hönisch3,4, J. Kim3,4, L. Pena5, M. Jaume-Seguí5 and M. Yehudai3,4

The mid-Pleistocene transition marks the final turn of the Earth system towards repeated major ice ages after ~900,000 years ago. Recent advances in paleoceanographic research provide insight into how ocean processes facilitated the climate changes at that time.

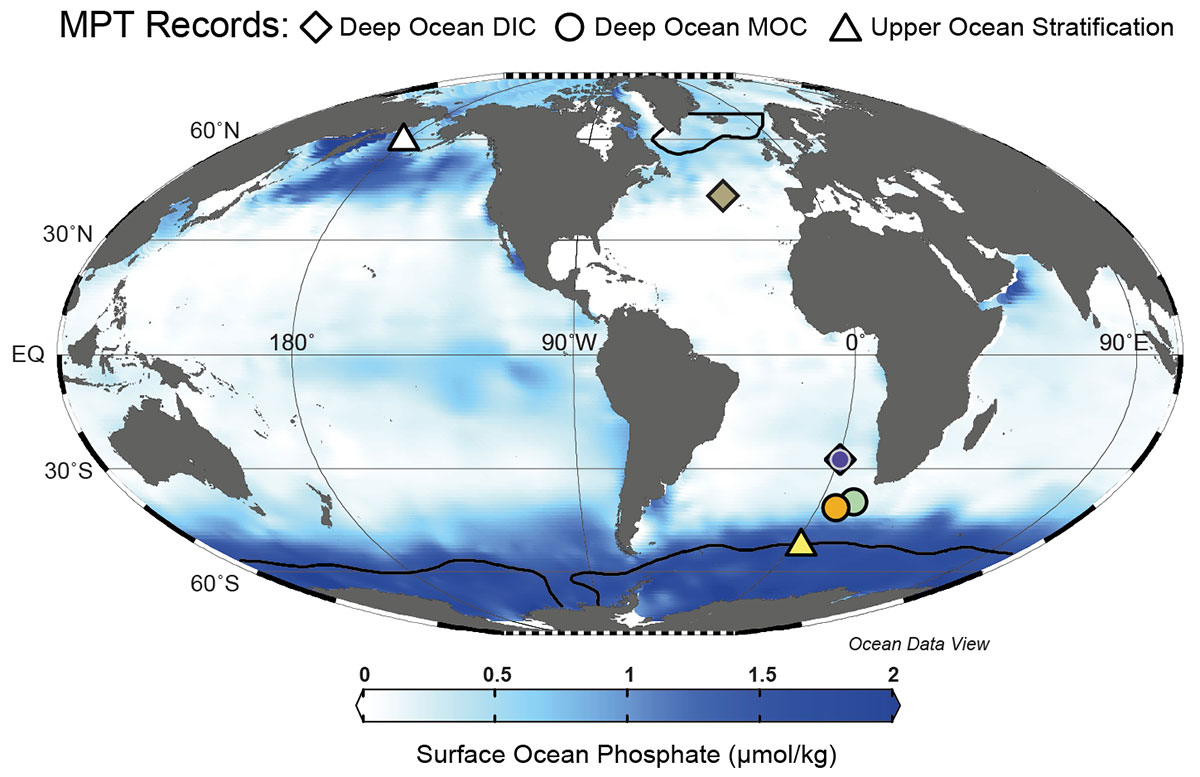

Approximately 900,000 years ago (900 kyr BP), ice ages switched from occurring every 41 kyr to every 100 kyr, lengthening in duration, and strengthening in terms of cooling and ice volume. This "mid-Pleistocene transition" (MPT) occurred without notable changes in Earth's orbit around the sun (i.e. incoming solar radiation). Lacking a defined external trigger, the MPT must represent a fundamental reorganization of Earth's internal climate system, including its greenhouse gas composition, ocean circulation, seawater chemistry, and/or development of more favorable conditions for ice-sheet growth. Recent advances in paleoceanography have made significant progress towards identifying when, how, and why the different components of Earth's climate system changed across the MPT. Here we summarize the biogeochemical insights gleaned from ocean sediments that directly reflect on the global carbon cycle (Fig. 1).

The global climate state of the mid-Pleistocene can be inferred from the benthic foraminiferal oxygen isotope stack of Lisiecki and Raymo (2005) (Fig. 2a), which integrates deep-ocean temperatures and global ice volume. This record shows the MPT as the transition from 41-kyr glacial cycles prior to 1250 kyr BP to dominant 100-kyr glacial cycles by 700 kyr BP (Fig. 2, light blue shading). Within this interval, an anomalously weak interglacial stands out at 900 kyr BP (the "900 ka event"), at the midpoint of what is considered the first 100-kyr glacial cycle (Fig. 2, dark blue shading; Clark et al. 2006).

Proposed explanations for the MPT often invoke declining atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) as a fundamental tool to change the climate response to orbital forcing (Clark et al. 2006). Available CO2 reconstructions during this time period are of low temporal resolution but suggest that glacial CO2 decreased by 20-40 ppm sometime between ca. 1000 and ca. 800 kyr BP (Fig. 2b). The ocean most likely caused this CO2 decline via enhanced biological CO2 uptake and/or reduced release of sequestered CO2 back to the atmosphere. General Pleistocene model simulations (Chalk et al. 2017; Hain et al. 2010) highlight three pathways for glacial ocean CO2 sequestration: weaker deep-ocean circulation, increased ocean biological productivity through iron fertilization, and reduced CO2 exchange between deep waters and the ocean surface (broadly termed "stratification"). The common premise behind these pathways is that the missing atmospheric CO2 was trapped in the deep ocean.

Records of ocean circulation

Earlier attempts to reconstruct deep-ocean circulation across the MPT relied on benthic foraminiferal carbon isotope ratios (δ13C). However, regional biology, air-sea gas exchange, and the size of the terrestrial biosphere also impact deep-ocean δ13C, hindering quantitative circulation reconstructions (Lynch-Stieglitz and Marchitto 2014). In contrast, neodymium isotopes (εNd) provide a potentially quantitative approach to separate deep-ocean waters of different geographical origins (Blaser et al. this issue). Distinct εNd values for North Atlantic-sourced and Pacific-sourced deep waters are set by weathering of older and younger continental material into each basin, respectively. In the modern ocean, Nd isotopes behave "quasi-conservatively"; that is, they reflect water-mass mixing, and are not substantially fractionated by biological or physical processes. Moreover, North Atlantic and Pacific end-member εNd values have remained approximately constant over the Pleistocene (Pena and Goldstein 2014).

Across the MPT, ocean circulation has been reconstructed from εNd at three South Atlantic locations (Fig. 1; Farmer et al. 2019; Pena and Goldstein 2014). All three records show a dramatic εNd increase following the ca. 950 kyr BP interglacial, indicating reduced North Atlantic deep-water formation and a relatively greater contribution of Pacific-sourced deep water. The elevated εNd values lasted for ca. 100 kyr, right through the ca. 910 kyr BP interglacial (Fig. 2c; Pena and Goldstein 2014). This also marked a transition in glacial deep Atlantic circulation, with weaker circulation (higher εNd) evident in all studied glacials after 950 kyr BP compared to glacials before 950 kyr BP. Intriguingly, this North Atlantic circulation weakening broadly overlaps with the "900 ka event" and the likely period of glacial CO2 decline (Fig. 2a-c).

Ocean impacts on atmospheric CO2

Proxy constraints on ocean-carbon chemistry reveal how weakened ocean circulation may have impacted CO2. Using the elemental ratios B/Ca and Cd/Ca in benthic foraminifera, Lear et al. (2016), Sosdian et al. (2018), and Farmer et al. (2019) observed that glacial deep waters became significantly more "corrosive" (lower carbonate ion concentration) and nutrient-enriched after 950 kyr BP throughout the Atlantic Ocean. Translated to total dissolved carbon, these observations support a ~50 µmol/kg increase during glacials after 950 kyr BP (Fig. 2d), equivalent to a 50 billion ton increase in carbon inventory throughout the deep Atlantic (Farmer et al. 2019). Pairing this information with εNd, Farmer et al. (2019) demonstrated that this deep-ocean carbon accumulation coincided with weakened deep Atlantic Ocean circulation (Fig. 2c-d), suggesting that weaker circulation facilitated accumulation of carbon and other nutrients in the deep Atlantic.

The implications of deep Atlantic carbon storage on CO2 are difficult to quantify because no simple equivalence exists between carbon concentration in the deep Atlantic Ocean and atmospheric CO2. In model simulations, the magnitude of CO2 reduction from weaker Atlantic circulation depends upon nutrient consumption in the surface Southern Ocean (Hain et al. 2010); with higher nutrient consumption, CO2 sequestration is strengthened. Martínez-Garcia et al. (2011) reconstructed iron flux to the Subantarctic Southern Ocean, finding that peak glacial iron input increased around the beginning of the MPT (ca. 1250 kyr BP), with integrated glacial iron input increasing more gradually over the MPT (Fig. 2e). If this flux represents bioavailable iron, then increasing Subantarctic iron fertilization across the MPT would have increased ocean CO2 sequestration (Fig. 2e; Chalk et al. 2017; Martínez-García et al. 2011). Addressing the hypothesis of increased stratification, Hasenfratz et al. (2019) reconstructed the glacial density contrast between surface and deep waters in the Antarctic Zone of the Southern Ocean, finding an increased density gradient around 700 kyr BP indicating a stronger halocline and longer surface-ocean residence time (Fig. 2f). This implies that a water-column density barrier to CO2 outgassing in the Southern Ocean strengthened by the end of the MPT.

In summary, three key oceanic pathways for atmospheric CO2 drawdown – deep Atlantic Ocean circulation, Subantarctic iron fertilization, and Southern Ocean stratification – all shifted towards favoring a stronger ocean CO2 sink and reduced atmospheric CO2 across the MPT. Yet all three pathways differ in their timing, and these scenarios are not necessarily exhaustive. For example, Kender et al. (2018) argue for enhanced stratification in the Bering Sea after 950 kyr BP (Fig. 1, white triangle), which may have also amplified oceanic CO2 drawdown.

Thus, evaluating the relative and cumulative CO2 impact of these pathways is an important focus for future MPT research. At the same time, sparse records of key ocean-CO2 pathways across the MPT must be expanded – particularly from the Pacific, which is the largest carbon reservoir in the modern ocean (Fig. 1). High-resolution atmospheric CO2 reconstructions are also needed to constrain the precise timing of MPT CO2 change, especially around 900 kyr BP, and to evaluate the relative importance of different oceanic processes (Fig. 2b). By expanding these proxy applications and integrating available evidence, paleoclimatologists will progress towards a mechanistic understanding of the controls on this crucial window of Earth's climate evolution, encompassing the rise of hominids and the background climate that mankind is altering today.

affiliations

1Department of Geosciences, Princeton University, NJ, USA

2Max-Planck Institute for Chemistry, Mainz, Germany

3Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

4Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, NY, USA

5Department of Earth and Ocean Dynamics, University of Barcelona, Spain

contact

Jesse R. Farmer: jesse.farmer princeton.edu

princeton.edu

references

Bereiter B et al. (2015) Geophys Res Lett 42: 542-549

Chalk TB et al. (2017) Proc Natl Acad Sci 114: 13114-13119

Clark PU et al. (2006) Quat Sci Rev 25: 3150-3184

Dyez K et al. (2018) Paleoceanogr Paleocl 33: 1270-1291

Farmer JR et al. (2019) Nat Geosci 12: 355-360

Hasenfratz A et al. (2019) Science 363: 1080-1084

Hain MP et al. (2010) Glob Biogeochem Cy 24: GB40239

Higgins J et al. (2015) Proc Natl Acad Sci 112: 6887-6891

Kender et al. (2018) Nat Commun 9: 5386

Lauvset SK et al. (2016) Earth Syst Sci Data 8: 325-340

Lear CH et al. (2016) Geology 44: 1035-1038

Lisiecki L, Raymo M (2005) Paleoceanography 20: PA1009

Lynch-Stieglitz J, Marchitto TM (2014) Treatise on Geochemistry (2nd Edition): 438-451

Martínez-Garcia A et al. (2011) Nature 476: 312-315