- Home

- Publications

- PAGES Magazine

- A Coordinated Modeling Assessment of The Climate Response To Volcanic Forcing

A coordinated modeling assessment of the climate response to volcanic forcing

Davide Zanchettin, C. Timmreck, M. Khodri, A. Robock, A. Rubino, A. Schmidt and M. Toohey

Past Global Changes Magazine

23(2)

54-55

2015

Davide Zanchettin1, C. Timmreck2, M. Khodri3, A. Robock4, A. Rubino1, A. Schmidt5 and M. Toohey2,6

Simulating volcanically-forced climate variability is a challenging task for climate models. The model intercomparison project on the climate response to volcanic forcing (VolMIP) defines a protocol for idealized volcanic-perturbation experiments to improve comparability of results across different climate models.

Stratospheric aerosols originating from volcanic sulfur emissions are a critical part of the natural forcing driving interannual-to-multidecadal climate evolution. In its 2013 assessment report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) affirms strong advances had been made in understanding volcanic aerosols and constraining associated forcing estimates compared with previous assessments (Myhre et al. 2013). Challenging the high confidence in volcanic forcing estimates reported by the IPCC (see Table 8.5 in Myhre et al. 2013), climate model results show some gaps in our understanding of the climate’s response to volcanic eruptions. For example the largest uncertainties in the estimates of radiative forcing from historical simulations performed using state-of-the-art climate models occur during periods of strong volcanic activity (Santer et al. 2014); climate models generally do not produce robust dynamical responses to volcanic eruptions (e.g. Driscoll et al. 2012; Ding et al. 2014) and tend to overestimate the observed post-eruption global surface cooling (Marotzke and Forster 2015); and simulated temperatures around major volcanic events of the last millennium often disagree with corresponding reconstructed changes (e.g. Mann et al. 2012; Anchukaitis et al. 2012).

The key question then is whether the lack of robustness in models’ behavior mostly depends on insufficient representation of climate processes, or other substantial sources of uncertainty, such as the imposed volcanic forcing. The lack of agreement between model results is mainly due to differences in the model’s characteristics, such as spatial resolution and implementation of volcanic forcing (e.g. Timmreck 2012). Nevertheless, whereas recent volcanic eruptions have been well observed and forcing estimates relatively well constrained, uncertainties grow considerably for events that occurred in the more remote past. For such eruptions, which contribute substantially to our understanding given the few instrumentally observed events, forcing characteristics must be reconstructed based on indirect evidence. This implies a lack of detail and large uncertainties regarding the climatically relevant parameters related to the source (especially the magnitude of the eruption), and to the stratospheric aerosol properties such as spatial extent of the cloud, optical depth, and aerosol size distribution (e.g. Timmreck 2012). All these large uncertainties are reflected in the occasionally substantial inconsistencies between available volcanological datasets (Sigl et al. 2014). Furthermore, internal climate variability and the presence of other forcing factors contribute to determine which mechanisms are activated in response to individual events (e.g. Zanchettin et al. 2013). It is therefore difficult to constrain the simulated responses to eruptions that occurred before the instrumental period, for which knowledge about the background climate conditions is poor.

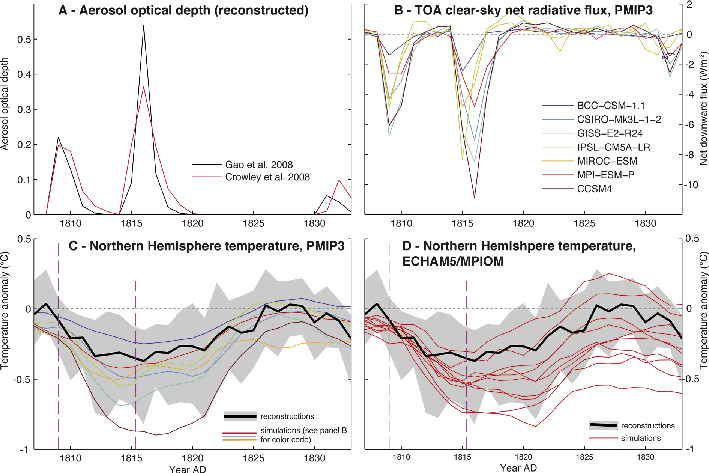

It is thus unsurprising that different simulations, either performed with different climate models or with the same climate model, and climate reconstructions tell different, often divergent stories about the post-eruption climate evolution. This occurred, for instance, in the case of the 1815 Tambora event, the largest-magnitude volcanic eruption of the past five centuries (Fig. 1).

Coordinated model intercomparisons

The continuing development of more accurate histories of past eruptions (e.g. Sigl et al. 2014) and more realistic volcanic forcing datasets (e.g. Arfeuille et al. 2013) promises to improve climate model simulations of past volcanic events. This alone, however, is not enough to discern the individual contributions to uncertainty from the bulk of the varied factors illustrated above. It is also necessary to frame modeling activities within standardized experiments designed to systematically tackle specific uncertainty factors.

The ongoing Model Intercomparison Project on the climatic response to Volcanic forcing (VolMIP) has defined a common protocol to subject coupled climate models to the same volcanic forcing, thus aiming for negligible across-model differences in the applied radiative forcing (e.g. Fig. 1b) in order to focus on the climate response. The coordinated experiments will assess the causes of across-model spread linked to the different treatment of physical processes, and separate such model uncertainties from uncertainties in the forcing and internal variability.

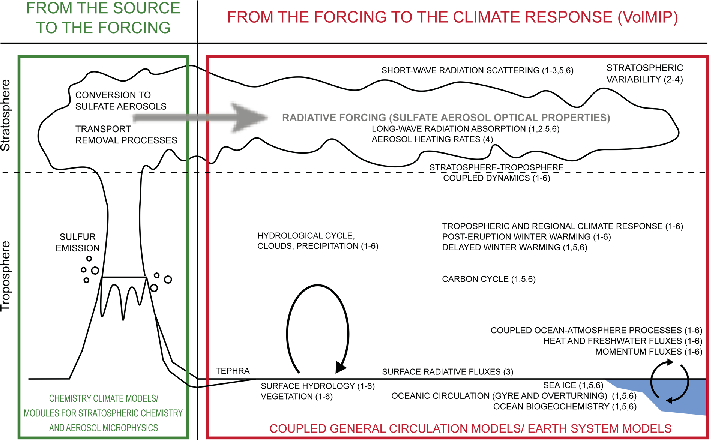

VolMIP focuses on the simulated processes that determine two main aspects of climate response to large volcanic eruptions: (i) the immediate dynamical alteration of atmospheric circulation triggered by the volcanically-induced stratospheric thermal anomaly and the associated variations in regional near-surface responses; and (ii) the decadal-scale response of the oceanic thermohaline and gyre circulations and associated long-term changes in heat transport and ocean-atmosphere coupling.

The VolMIP experiments

VolMIP defines a set of idealized volcanic perturbations based on historical eruptions. In this context, “idealized” means that the volcanic forcing is derived from radiation parameters of documented eruptions and the experiments do not include information about the actual climate conditions when these events occurred. The experiments are designed as ensemble simulations, with sets of initial climate states sampled from an unperturbed preindustrial simulation. By exploring very different initial conditions, VolMIP aims to constrain the range of post-eruption evolutions that arise from the interplay between ongoing internal climate variability and the imposed radiative perturbation, thus clarifying how much an accurate knowledge of background climate conditions matters when reproducing past volcanic events. Specific attention is given to the concomitant phasing of two dominant modes of climate variability: the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, the most important source of interannual climate variability, and the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, a measure of the strength of the oceanic thermohaline circulation.

The proposed core and sensitivity experiments (Fig. 2) reflect VolMIP’s twofold strategy:

• VolShort: a set of experiments focusing on the seasonal-to-interannual atmospheric response to a 1991 Pinatubo-like volcanic eruption. The goal is to discriminate between the uncertainties that are due to internal variability (within-model spread) and those due to model characteristics (across-model spread). The core full-forcing experiment is supported by sensitivity experiments designed to determine the roles of surface cooling and stratospheric warming – the two main features of short-term post-eruption climate variability – in controlling the dynamical response of the atmosphere. Additional experiments address the impact of volcanic forcing on seasonal-to-interannual climate predictability.

• VolLong: a set of experiments addressing the long-term (up to the decadal time scale) climate response to volcanic eruptions featuring a high signal-to-noise ratio in the global-average surface temperature response. Focus is on the signal propagation pathways of volcanic perturbations within the coupled atmosphere-ocean system, the associated determinant dynamical processes and their representation across models. The 1815 Tambora eruption is chosen as reference for the core experiment, as available climate-proxy data provide information on both eruption characteristics and climate response. A 1783 Laki-like, high-latitude eruption and idealized volcanic clusters (close successions of large volcanic eruptions) are also contemplated in this set of experiments. Provision of forcing input data for these simulations is an integral part of VolMIP.

Conclusions

Improvement in understanding the dominant mechanisms behind simulated post-eruption climate evolution crucially depends on coordinated modeling activities that address the individual sources of uncertainty separately. By subjecting different models to well-constrained volcanic forcing, VolMIP promises to make significant progress in our knowledge of the physical processes that determine the climate’s response to volcanic forcing. By further clarifying the relative role of internal and externally-forced climate variability during periods of strong radiative forcing, VolMIP can enhance our ability to accurately simulate past, as well as future, climates.

affiliations

1Department of Environmental Sciences, Informatics and Statistics, University of Venice, Italy

2Max-Planck-Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg, Germany

3IRD/IPSL/Laboratoire d'Océanographie et du Climat, Paris, France

4Department of Environmental Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, USA

5School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, UK

6GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Germany

contact

Davide Zanchettin: davide.zanchettin unive.it

unive.it

references

Anchukaitis K et al. (2012) Nat Geosci 5: 836-837

Arfeuille F et al. (2013) Atmos Chem Phys 13: 11221-11234

Braconnot P et al. (2012) Nature Clim Change 2: 417-424

Crowley TJ et al. (2008) PAGES News 16: 22-23

Ding Y et al. (2014) J Geophys Res 119: 5622-5637

Driscoll S et al. (2012) J Geophys Res 117, doi:10.1029/2012JD017607

Frank DC et al. (2010) Nature 463: 527-530

Gao C et al (2008) J Geophys Res 113, doi:10.1029/2008JD010239

Mann ME et al. (2012) Nature Geosci 5: 202-205

Marotzke J, Forster P (2015) Nature 517: 565-570

Santer BD et al. (2014) Nature Geosci 7: 185-189

Sigl M et al. (2014) Nature Clim Change 4: 693-697