- Home

- Publications

- PAGES Magazine

- Ice Core-based Isotopic Constraints On Past Carbon Cycle Changes

Ice core-based isotopic constraints on past carbon cycle changes

Hubertus Fischer, J. Schmitt, S. Eggleston, R. Schneider, J. Elsig, F. Joos, M. Leuenberger, T.F. Stocker, P. Köhler, V. Brovkin and J. Chappellaz

Past Global Changes Magazine

23(1)

12-13

2015

Hubertus Fischer1, J. Schmitt1, S. Eggleston1, R. Schneider1, J. Elsig1, F. Joos1, M. Leuenberger1, T.F. Stocker1, P. Köhler2, V. Brovkin3 and J. Chappellaz4

High-precision ice core data on both atmospheric CO2 concentrations and their carbon isotopic composition (δ13Catm) provide improved constraints on the marine and terrestrial processes responsible for carbon cycle changes during the last two interglacials and the preceding glacial/interglacial transitions.

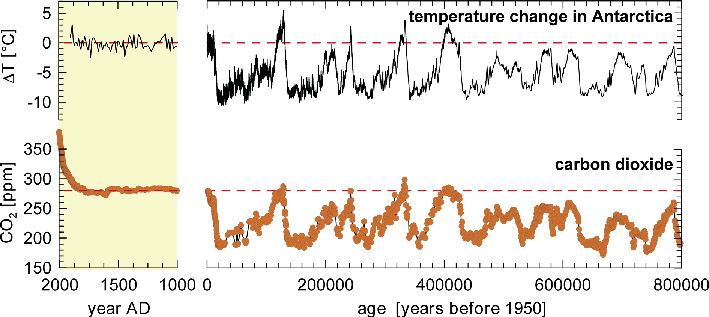

CO2 represents the most important greenhouse gas released into the atmosphere as a result of human activity. The majority of our knowledge on the increase in CO2 since the start of the industrialization comes from ice cores, which complement the direct atmospheric CO2 measurements obtained at Mauna Loa since the 1950s. The combined CO2 record shows an unambiguous anthropogenic CO2 increase over the last 150 years from 280 to about 400 ppm in 2014. Values above 300 ppm are unprecedented in the long-term ice core record covering the last 800,000 years with natural CO2 concentrations varying between interglacial and glacial bounds of about 280 and 180 ppm, respectively (Fig. 1; Lüthi et al. 2008; Petit et al. 1999). The record also showed that even during rather stable interglacial conditions, CO2 concentrations changed in response to long-term carbon cycle changes (Elsig et al. 2009). Although past atmospheric CO2 concentrations are known with high precision, the causes of the preindustrial CO2 changes cannot be easily attributed to individual processes. Substantial progress could come from better estimates of past changes in the carbon stored by the biosphere or from using stable carbon isotopes to constrain sources and sinks of carbon and exchange processes with the atmosphere.

The vast majority of the carbon cycling in the Earth system on multi-millennial timescales resides in the ocean. Accordingly, the global δ13C of inorganic carbon dissolved in seawater (δ13CDIC) may provide the best constraint on past carbon cycle changes. However, a global compilation of δ13CDIC from marine sediment records is hampered by insufficient spatial representation of vast ocean regions, the limited temporal resolution of many sediment records, and substantial chronologic uncertainties. The alternative, to reconstruct the mean δ13C record of the well-mixed atmosphere (δ13Catm) from the fossil air contained in Antarctic ice cores, has been a long-standing quest. Latest analytical progress that improved the measurement error while at the same time cutting down sample size by an order of magnitude has allowed us to gain this information from ice cores with the required precision and temporal resolution.

The enigma of glacial/interglacial CO2 changes

The cause of the glacial/interglacial 80-100 ppm increase of atmospheric CO2 represents a long-standing question in paleoclimate research. Several processes have been implied. These include Southern Ocean ventilation by wind or buoyancy feedbacks, iron fertilization of the marine biosphere in the Southern Ocean, changes in the re-mineralization depth of organic carbon, release of permafrost carbon during the deglaciation, decreased solubility due to ocean warming, changes in air/sea gas exchange due to changing sea ice cover, climate-induced changes in weathering changes rates, and marine carbonate feedbacks (Ciais et al. 2012; Fischer et al. 2010; Köhler and Fischer 2006; Menviel et al. 2012). However, none of these processes alone is able to explain the glacial/interglacial CO2 change.

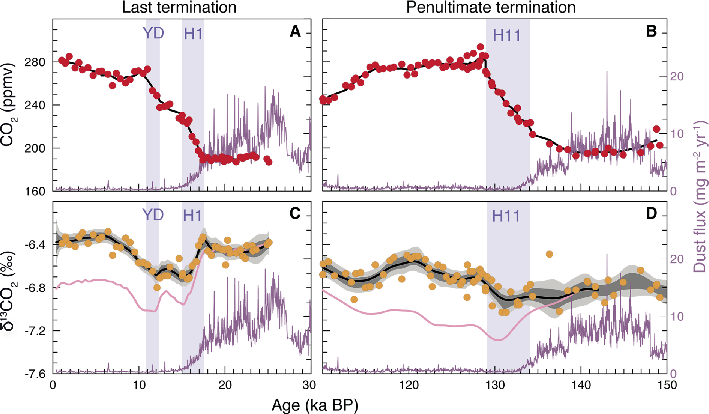

Our new δ13Catm data from the air trapped in the Antarctic EPICA Dome C ice core, provide improved constraints to revisit the enigma of deglacial CO2 increase (Fig. 2). Mean δ13Catm levels during peak glacials and interglacials were not much different, despite different CO2 concentrations and the substantially altered climate system. This implies that the δ13Catm record is the sum of several factors that balance each other to a large extent. For example, just considering the sea surface temperature-dependent fractionation of CO2 between the atmosphere and the ocean surface, approximately 0.4‰ lower δ13Catm values are expected for interglacials (Fig. 2).

Our δ13Catm data (Lourantou et al. 2010; Schmitt et al. 2012) from the last two major deglaciations suggest a sequence of processes that drove atmospheric CO2 changes during different stages of the transition from glacial conditions into a milder interglacial world.

• At the start of the transitions, upwelling of old 13C-depleted waters in the Southern Ocean increased the release of CO2 to the atmosphere. This process was likely synchronous with a demise in iron-stimulated bioproductivity in the Southern Ocean, when atmospheric dust concentrations declined rapidly.

• This was followed by the gradual growth of terrestrial carbon storage in vegetation, soil, and peatlands as evidenced by the slow δ13Catm increase. This process reached well into the subsequent interglacials. Termination I was special in that it was interrupted by another upwelling event synchronous to the Younger Dryas in the Northern Hemisphere.

The Holocene - natural changes or early anthropogenic influence?

The Holocene is often described as a rather stable period in climate history. Nevertheless, from 7 ka BP to the preindustrial era the CO2 concentration increased by ~20 ppm, i.e. by a quarter of the glacial/interglacial change. Such a CO2 increase is not found during the preceding three interglacials (Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 5.5, 7.5 or 9.3), although increases at similar rates can be found in MIS 11.3 or 15.5. This gave rise to the hypothesis that the Holocene CO2 increase may be unique and was caused by early anthropogenic land use (Ruddiman 2003). However, an anthropogenic release of isotopically light terrestrial carbon would lead to a decrease in δ13Catm over the last 7000 years, which is not observed in our record (Fig. 2; Elsig et al. 2009). The expected anthropogenic δ13Catm decline could in principle have been compensated by a concurrent natural build-up of peat at higher latitudes, but in that case atmospheric CO2 should not have increased. In any case, a substantial early human influence on atmospheric CO2 is difficult to reconcile with the ice core evidence. Based on terrestrial carbon cycle model results (Stocker et al. 2011), anthropogenic land-use is also unlikely to have released sufficient carbon during the last 7000 years to explain the 20 ppm CO2 increase.

However, the carbon cycle may not only be altered by terrestrial processes during the Holocene, but also has a long-term ocean memory. The long-term carbonate compensation feedback (the re-equilibration of carbonate chemistry in the ocean) to carbon cycle changes occurring in the preceding deglaciation and enhanced shallow-water carbonate sedimentation during the Holocene due to sea level rise are acting on multi-millennial time scales and lead to a delayed increase in atmospheric CO2 as observed in the ice core record without changing δ13Catm (Elsig et al. 2009; Kleinen et al. 2010; Menviel and Joos 2012).

If so, why is there no similar CO2 increase observed during MIS 5.5? Explanations probably lie in the individual configuration of orbital forcing of each interglacial but also in the preceding deglacial history. For example the unique Younger Dryas event during Termination I may have disturbed the deglacial carbon cycle re-adjustment.

Outlook

The examples shown from the last two glacial-interglacial transitions demonstrate the value of high-quality δ13Catm data from Antarctic ice cores. However, maximum insight into the past carbon cycle can only be gained from joint atmospheric, terrestrial, and marine carbon cycle information in combination with coupled carbon cycle models. A stringent test for our carbon cycle understanding will be a future “Oldest Ice” ice core covering the last 1.5 Ma, which would provide the history of CO2 and δ13Catm over the mid-Pleistocene Revolution, when the glacial/interglacial cyclicity changed from a 40,000 year period driven by obliquity changes of the Earth’s axis to the well-known 100,000 year cycles in the later Quaternary.

affiliations

1Climate and Environmental Physics, Physics Institute and Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research, University of Bern, Switzerland

2Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany

3Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg, Germany

4UJF–Grenoble 1/CNRS, Laboratoire de Glaciologie et Géophysique de l’Environnement (LGGE), Grenoble, France

contact

Hubertus Fischer: hubertus.fischer climate.unibe.ch

climate.unibe.ch

references

Ciais P et al. (2012) Nat Geosci 5: 74-79

Elsig J et al. (2009) Nature 461: 507-510

EPICA community members (2004) Nature 429: 623-628

Kleinen T et al. (2010) Geophys Res Lett 37, doi:10.1029/2009GL041391

Lambert F et al. (2012) Clim Past 8: 609-623

Lourantou A et al. (2010) Global Biogeochem Cycles 24, doi:10.1029/2009GB003545

Lüthi D et al. (2008) Nature 453: 379-382

MacFarling Meure C et al. (2006) Geophys Res Lett 33, doi:10.1029/2006GL026152

Menviel L, Joos F (2012) Paleoceanography 27, doi:10.1029/2011PA002224

Menviel L et al. (2012) Quat Sci Rev 56: 46-68

Petit JR et al. (1999) Nature 399: 429-436

Ruddiman WF (2003) Climatic Change 61: 261-293

Schmitt J et al. (2012) Science 336: 711-714