- Home

- Publications

- PAGES Magazine

- Monsoon Climate - Will Summer Rain Increase or Decrease In Monsoon Regions? [Past]

Monsoon climate - Will summer rain increase or decrease in monsoon regions? [Past]

Hai Cheng, Ashish Sinha and Steven M. Colman

PAGES news

20(1)

27

2012

Hai Cheng1,2, Ashish Sinha3 and Steven M. Colman4

1Institute of Global Environmental Change, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, China; cheng021 umn.edu

umn.edu

2Department of Earth Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA

3Department of Earth Science, California State University, Carson, USA

4Large Lakes Observatory, University of Minnesota, Duluth, USA

Arab sailors, who traded extensively along the coasts of Arabia and India, used the word mausim, which means “seasons”, to describe the large-scale changes in the winds over the Arabian Sea. The word “monsoon” likely originated from mausim and today it is applied to describe the tropical-subtropical seasonal reversals in the atmospheric circulation and associated precipitation over Asia-Australia, the Americas, and Africa.

The regional monsoons have long been viewed as gigantic, thermally-driven, land-sea breezes (Wang 2009). With the advent of satellite-based observations, a holistic view of monsoon has emerged which considers regional monsoons to be interactive components of a single global monsoon (GM) system. The GM is coordinated primarily by the annual cycle of solar radiation and the corresponding reversal of land-sea temperature gradients, along with the seasonal march of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ).

A vast body of data describing “paleo-monsoons” (PM) has been assembled from proxy archives, such as ice cores, marine and lake sediments, pollen spectra, tree-rings, loess, speleothems, and documentary evidence. Different archives record different aspects of the PM, and most are subject to complications such as thresholds in the climate or recording systems. In most cases it is difficult to extract detailed paleo-seasonality information (e.g. length or precipitation amounts of the summer rainy season) from such archives. Nonetheless, the proxy records describe PM variations on the time scales permitted by sample resolutions and chronologic constraints.

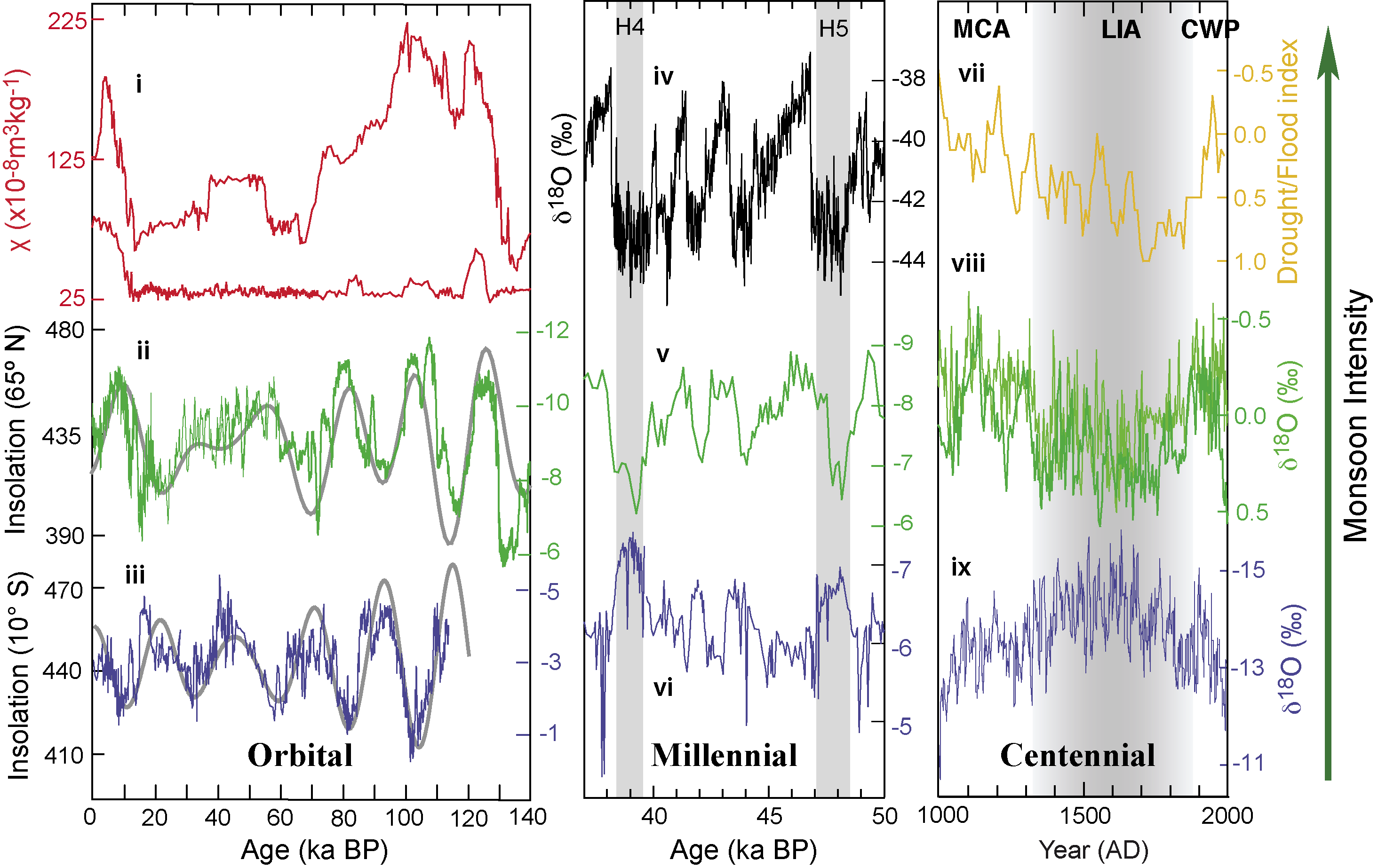

The PM phenomenon can be traced back to the deep time (106 to 108 years) (Wang 2009), but much focus has been put on reconstructing PM on orbital to decadal scales. Although the mechanisms driving PM oscillations are quite distinct on different time scales, the spatial-temporal patterns of PM variability are indeed comparable to the observed annual variations of the modern GM. For example, glacial-interglacial PM variability has been shown to be driven primarily by changes in summer insolation and global ice volume, and was possibly modulated by cross-equatorial pressure gradients (An et al. 2011). On orbital scales, PMs oscillated between strong states (during high summer insolation) and weak states (during low summer insolation), respectively, hence exhibiting an anti-phase relationship between the two hemispheres (Fig. 1, left panel).

A number of proxy records of PM from both hemispheres reveal characteristic millennial-centennial length variability (Fig. 1, middle and right panel). On these time scales, PM oscillated between two contrasting states, with weak PM in the Northern and strong PM in the Southern Hemisphere and vice-versa. This pattern conforms remarkably well to climate model simulations that link changes in PM with changes in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, which result in changes in interhemispheric temperature contrast and in turn, the mean latitudinal location of the ITCZ.

Human cultural history in monsoon regions is rich with accounts of severe climatic impacts related to changes in monsoon rainfall. Indeed, annually-resolved proxy records of PM covering the last few millennia reveal marked decadal-scale changes in spatiotemporal patterns of rainfall that are clearly outside the range of instrumental measurements of monsoon variability (e.g. Zhang et al. 2008; Bird et al. 2011; Tan et al. 2011; Sinha et al. 2011).

Most proxy studies indicate that PM strength across a range of time scales was modulated by near-surface land-sea thermal contrasts. However, the Asian Monsoon (AM) at its fringes and the South American Monsoon (SAM) seem to have waned over the past 50-100 years (Fig. 1, right panel). This is anomalous in the context of global warming, which presumably increases summer land-sea thermal contrasts and thus intensifies summer monsoons. If the observed waning trend of summer monsoon in fringe regions is linked to global warming over the last century and the total moisture evaporated from ocean increases in a future warmer world, one may expect persistent weaker summer monsoons in fringe areas of the monsoon, along with increased rainfall at lower latitudes. However, this inference must be weighed against the considerable uncertainty in future monsoon behavior that may stem from continued anthropogenic impacts such as aerosol loading and land-use change.

selected references

Full reference list online under: http://pastglobalchanges.org/products/newsletters/ref2012_1.pdf

Sinha A et al. (2011) Quaternary Science Reviews 30: 47-62

Sun YB et al. (2006) Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 7, doi: 10.1029/2006GC001287

Tan L et al. (2011) Climate of the Past 7: 685-692

Wang PX (2009) Chinese Science Bulletin 54: 1113-1136