- Home

- Taxonomy

- Term

- PAGES Magazine Articles

PAGES Magazine articles

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2023

Past Global Changes Magazine

Natasha L.M. Barlow1,

A. Rovere2,3 and A.J. Meltzner4,5

A. Rovere2,3 and A.J. Meltzner4,5

4th PALSEA workshop, Singapore and online, 17–20 July 2022

The fourth meeting of the current phase of the PALeo constraints on SEA level rise (PALSEA) working group (WG) (2019–2022) (pastglobalchanges.org/palsea) was held in Singapore in July 2022, following the World Climate Research Programme sea level Grand Challenge meeting (pastglobalchanges.org/calendar/129138). The meeting was co-organized by PALSEA, and Aron Meltzner and Adam Switzer, from the Earth Observatory of Singapore (EOS), with support from EOS Director Ben Horton. The meeting focused on pulling together the lessons learnt from both the 2019–2022 phase of PALSEA, as well as the workshops that had gone before since PALSEA’s inception in 2008 on the topic of “paleo sea level and ice sheets for the Earth’s future”. This was the first time that a PALSEA workshop has been held in hybrid format. It was wonderful to reconnect face-to-face with the community, and provide more comprehensive access to the meeting.

The meeting started with a series of optional field trips, with many in-person attendees taking the opportunity to explore the landscapes of Singapore and the sea-level archives studied by the EOS research teams. An early morning boat took participants across the water to St. John’s and Lazarus islands to see fields of living and fossil microatolls that provide unique insights into relative sea level (Fig. 1). The mangroves at Pulau Ubin provided a first coring experience for some delegates, where they explored the use of wetland sea-level indicators. A third trip took a stroll through the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, followed by an amazing lunch!

A series of oral presentations, lightning talks and virtual poster sessions filled the following three days. Many early-career researchers were present at the meeting; for many, it was their first in-person conference due to COVID-19. Following PALSEA tradition, it was wonderful to see these researchers have the opportunity to present their science and explore other ideas, with a safe space to ask questions. Of particular note were significant developments in 3D Earth modeling (building on the 2021 PALSEA workshop), innovative approaches to reconstructing late Quaternary ice-sheet histories, and the application of artificial intelligence to proxy sea-level data. Several presentations also highlighted the improvements in open-access standardised sea-level and ice-sheet databases made by PALSEA and associated projects.

One of the main points of discussion was centred on the role of paleo sea-level and ice-sheet science in understanding the future, as perfectly highlighted by invited speaker Tamsin Edwards. In particular, concern was raised that a statement in IPCC AR6 Chapter 9, taken in isolation, might be misleading: “Given uncertainties in paleo sea level and polar paleoclimate, and limited temporal resolution of paleo sea level records, there is low confidence in the utility of paleo sea level records for quantitatively informing near-term GMSL change” (IPCC 2021).

The audience reported instances where such phrasing was taken out of context, diminishing the importance of paleo-climate research within the broader climate science discipline. We agree that the limitation of paleo data means that its application to modeling decadal climate change may be restricted, however it does not prevent their use in climate modeling on longer timescales. As a paleo sea-level and ice-sheet community, we concluded that it is essential to report the full AR6 quote where the line above follows with: “Nonetheless, the paleorecord does contextualise sea level and can test projection models” (IPCC 2021). These are the key roles paleoscience can play in the Earth’s future – and we must continue communicating this effectively.

PALSEA has now completed this phase as a formal PAGES WG. The outgoing leaders are working with an exciting new team who will lead the international sea-level and ice-sheet community to tackle the research challenges and priorities identified as part of the 2022 meeting. We thank all the participants who engaged in this workshop and the supporting organizations: PAGES, EOS and the International Union for Quaternary Research (INQUA).

affiliationS

1School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, UK

2DAIS, Department for Environmental Sciences, Statistics and Informatics, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Italy

3MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences and Faculty of Geosciences, University of Bremen, Germany

4Earth Observatory of Singapore, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

5Asian School of the Environment, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

contact

Natasha Barlow: n.l.m.barlow leeds.ac.uk

leeds.ac.uk

REFERENCES

IPCC (2021) Climate Change: The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2023

Past Global Changes Magazine

4th CRIAS workshop, Oslo, Norway, and online, 11–12 May 2023

Global warming has heightened scholarly and public concern over links between climate and conflict and has accelerated research into possible connections among extreme events, warfare, and political and intergroup conflict. Nevertheless, scholars have yet to reach firm consensus on past and present linkages between climate and conflict or a comprehensive integration of historical and current perspectives (Degroot 2018).

The workshop “Climate and Conflict Revisited: Perspectives from Past and Present” assembled researchers from the historical, social, and natural sciences to revisit the climate–conflict nexus (pastglobalchanges.org/calendar/136748). This event – a joint meeting of the PAGES Climate Reconstruction and Impacts from the Archives of Societies (CRIAS) (pastglobalchanges.org/crias) working group and the University of Oslo CLIMCULT project – took place at the Oslo Museum of Natural History. It included 15 presentations, with a public keynote address by Florian Krampe (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute) and a visit to the museum’s Klimahuset to explore public perceptions of climate change and conflict.

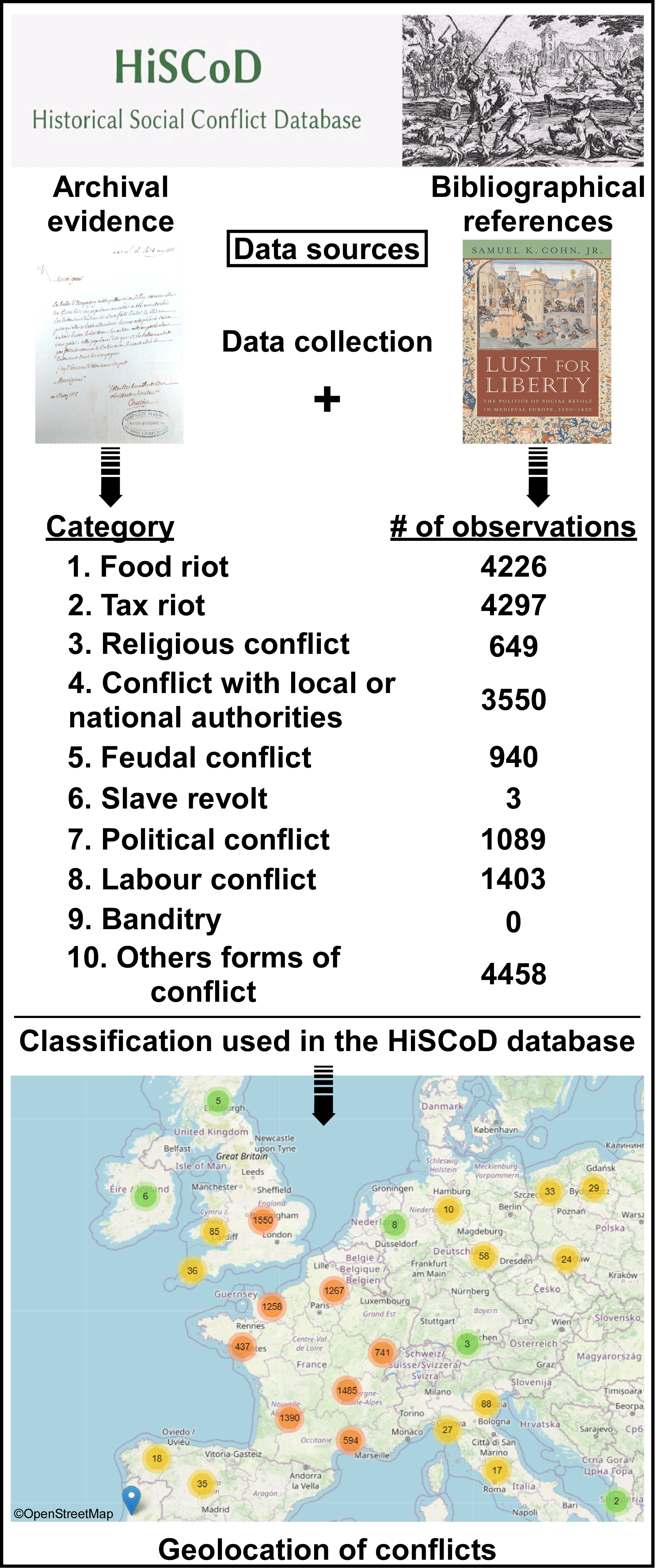

The first day’s sessions began with the archaeology of climate change and conflict during the Late Bronze Age and continued with case studies of medieval Iceland and Byzantine and Ottoman Macedonia. Christian Pfister (University of Bern) discussed pathways of causality between extreme weather and conflict in early modern Europe, and researchers presented new quantitative and qualitative analyses of climate and conflict in China and Central Europe from the 17th to 20th centuries. Stefan Döring (Peace Research Institute of Oslo) introduced studies of current climate change impacts on health and cooperation, followed by Natália Nascimento i Melo’s (University of Évora) exploration of climate change and impacts in museum exhibitions. The second day began with a session on new historical databases and applications for spatial and temporal analysis of climate-conflict links. These included Societal Impact Event Records (SIER) for Ming and Qing China, the Historical Social Conflict Database (HiSCoD) database for 12th–to 19th-century Europe, and a collection of witchcraft prosecutions in Catalonia, Spain. Final presentations from Cedric de Coning (University of Oslo) and Silviya Serafimova (University of Sofia) emphasized epistemic pluralism in contemporary climate–conflict studies and theoretical perspectives from peace studies.

|

|

Figure 1: An illustration of the Historical Social Conflict Database (HiSCoD; unicaen.fr/hiscod/accueil.html), one of several new databases for the study of historical climate, extreme events, and conflict presented at the workshop. Image credit: N. Maughan. |

Key themes emerged in workshop discussions, which demonstrated the importance of linking historical and contemporary perspectives. Several presentations explored climate variability and “slow violence” (Nixon 2013), such as withholding common resources or disrupting customary practices of coping during difficult seasons. Participants noted parallels between past and present pathways from climate to conflict, including the instrumentalization of extreme events to initiate or legitimize violence. Current research based on abundant climate and societal data indicates delayed and displaced impacts, arriving through complex pathways. This raised questions about how best to identify links between climate and conflict in historical data, where to find appropriate spatial and temporal scales for quantitative analysis, and how to overcome problems arising from incomplete or biased reporting in historical sources. Researchers in both current and historical fields also identified common challenges in communicating results, such as how to convey the balance between natural and human agency. Participants expressed hope that historical case studies illustrating past choices and possibilities could improve public messaging and refine both simplified histories of climate-driven conflict and reductionist projections of inevitable conflict under global warming.

The workshop concluded with a roundtable discussion of current needs and future possibilities in the field. Participants planned a thematic review explaining historical insights into climate and conflict for researchers in the social sciences and peace studies, as well as museums and public institutions. The meeting included more than two dozen participants representing over a dozen countries, as well as an international online audience. The CRIAS organizers hope for further representation from countries beyond Europe and East Asia in future meetings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the participants for their contributions, the Oslo Museum of Natural History for hosting the event, PAGES for support of early-career researchers, and the funders and organizers of the CLIMCULT project, which shared this workshop.

affiliationS

1Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Helsinki, Finland

2Department of History and Archaeology, University of Oslo, Norway

3German Maritime Museum / Leibniz Institute for Maritime History, Bremerhaven, Germany

4Lab I2M UMR-7373, Aix Marseille University, CNRS, Marseille, France

contact

Sam White: samuel.white helsinki.fi

helsinki.fi

REFERENCES

Nixon R (2013) Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard University Press, 368 pp

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2023

Past Global Changes Magazine

Nicole K. Sanderson 1,

1,

J. Loisel 2,

2,

A. Gallego-Sala 3,

3,

G. Anshari4,

N. Novita5,

K. Marcisz6,

M. Lamentowicz6,

M. Bąk6 and

D. Wochal6

J. Loisel

A. Gallego-Sala

G. Anshari4,

N. Novita5,

K. Marcisz6,

M. Lamentowicz6,

M. Bąk6 and

D. Wochal6

C-PEAT workshop, Pontiana, Indonesia, Poznań, Poland, Truckee, USA, and online, 8–12 May 2023

Carbon in peatlands through time

Peatlands play an important role in the global carbon cycle, namely as a large carbon store and a major source of methane emissions into the atmosphere. Across the globe, climate, peat fires, and land-use changes are impacting the peatland carbon balance and, in many cases, turning peatlands into net carbon sources. Peatlands are also unique ecosystems acting as global environmental archives – some tropical peats are dated back as far as 40,000 years old!

While conservation and restoration activities have gained in popularity and can slow down peat-carbon losses, a predictive understanding of peatlands’ complex responses to current and projected changes is critically needed, particularly for tropical peatland functioning and recent peatland dynamics (especially in the last ~100 years).

Our current (and incomplete) understanding hampers the pressing need to transfer knowledge on peat-carbon cycling to managers, practitioners, policymakers, as well as to communities; it also limits our capacity to integrate peatlands into Earth System Models that forecast feedbacks to the global carbon cycle and climate system.

The main goal of the Carbon in Peat on EArth through Time (C-PEAT) working group (WG) (pastglobalchanges.org/c-peat) is to understand peatland dynamics over different timescales, from the past millennia into modern times, and make predictions about their future behavior in the face of global, as well as local, changes. To do so, we use peat-core records to reconstruct past ecohydrological and paleoclimate changes, and link said past conditions with changes in peatland dynamics. These paleo datasets are combined with modern-day measurements (e.g. gas-flux data) and models. Our group members are also working on nature-based climate solutions, including peatland restoration and conservation.

A truly global (and low carbon) meeting

This year’s C-PEAT workshop (pastglobalchanges.org/calendar/136966) was held simultaneously in three international hubs (Indonesia, Poland and USA). While each hub had its own schedule of speakers and activities, all three hubs shared a similar research agenda (for the meeting guide and links to talks, see: shorturl.at/hjxJW). We also held daily two hour-long “global discussions” where all three hubs met online and shared the prior day’s key messages and ideas.

A total of 48 in-person and 16 online participants gave talks, and an additional 30 online participants took part in the workshop. Day 1 focused on setting a research agenda for tropical peatlands; days 2 and 3 were dedicated to issues and potential solutions to quantifying recent peatland carbon dynamics, and day 4 was devoted to sharing recent progress on our current data community products and looking back at the work that had been done during the second phase of our WG.

|

|

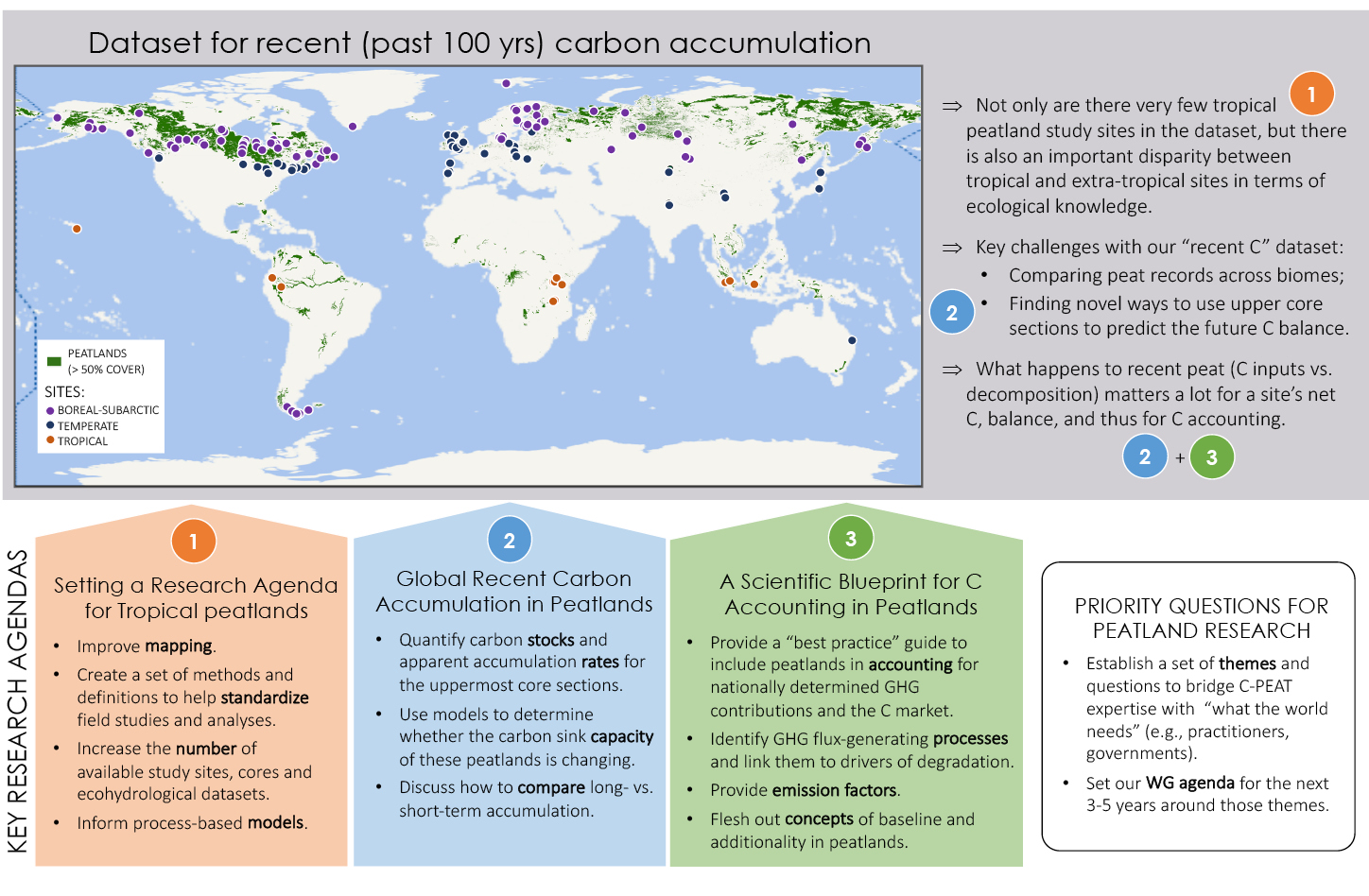

Figure 1: Key research agendas and priority questions for the future of peatland research and the C-PEAT working group. |

We also outlined our research priorities for the next phase of C-PEAT (Fig. 1) while discussing ways to keep our core identity as paleo-peat scientists. Indeed, our community of practice has rapidly broadened over the past few years and now includes modelers and modern-measurement scientists, restoration and conservation scientists, as well as stakeholders specializing in carbon accounting. On day 5, some hubs organized field trips for the local participants. Lastly, the workshop has greatly broadened our core of scientists, particularly early-career and from low-and-middle income countries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to the following organizations for funding support: Future Earth’s Past Global Changes (PAGES), The International Union for Quaternary Research (INQUA), UNESCO’s International Geoscience Programme (IGCP), The US National Science Foundation (NSF), Yayasan Konservasi Alam Nusantara/The Nature Conservancy Indonesia Business Unit, and Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland.

affiliationS

1Département de géographie, Université du Québec à Montréal, Canada

2Department of Geography, Texas A&M University, College Station, USA

3Department of Geography, University of Exeter, UK

4Universitas Tanjungpura, Pontianak, Indonesia

5Yayasan Konservasi Alam Nusantara, Jakarta, Indonesia

6Climate Change Ecology Research Unit, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland

contact

Julie Loisel: julieloisel tamu.edu

tamu.edu

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2023

Past Global Changes Magazine

QiaoyuCui1,

C. Kulkarni2,

E. Razanatsoa3,

Y. Li4,

J. Wu5,

M. Ji6 and

L. Zhou4

C. Kulkarni2,

E. Razanatsoa3,

Y. Li4,

J. Wu5,

M. Ji6 and

L. Zhou4

DiverseK workshop, Beijing, China, and online, 13–15 May 2023

Eastern Asian countries (including China, Mongolia, Korea and Japan) will face unprecedented socio-environmental challenges in the coming decades (IPCC 2021). Moreover, regional climate changes, together with land-use intensification and increasing livelihood demands, continue to represent a “perfect storm” in regions among the most populated in the world (Beddington 2009). A prime challenge for Asian countries is to identify a more sustainable, inclusive and spatially coherent approach to ecosystem management – a lack of which often results in conflicts between restoration targets and people’s needs (e.g. Colombaroli et al. 2021).

The hybrid workshop (pastglobalchanges.org/calendar/129272) organized by the DiverseK working group (WG) (pastglobalchanges.org/diversek), with a focus on Asian ecosystems through a combined paleoscience-policy lens, offered opportunities to delve deeper into the issue and brainstorm a practical role of paleoscience in addressing it. The in-person component of the workshop was held in Beijing, China, which happens to be the first-ever Past Global Changes (PAGES) workshop held in China. The workshop spoke to the scientific goals of the DiverseK WG, i.e. to provide a new integrative, cross-disciplinary evidence base to enable better decision-making on pressing environmental issues and local struggles. The steps toward implementing the “Paleoscience for Policy” approach were discussed in great detail at the workshop. The synthesis of ideas during two discussion sessions included: i) the development of a network among paleoecologists and stakeholders in Asia with a common goal of effective ecosystem management; ii) a dedicated discussion on the cross-comparison of management solutions under different national schemes within Asia (e.g. the steppe in China/Mongolia, fire management across India and China); and iii) the identification of best conservation approaches from the respective regions in light of the paleo-evidence base (pollen, macrofossils, disturbance regime indicators, and tree rings).

Two case studies presented at the workshop exemplified the existing challenges for conservation at species/community levels in forest and grassland ecosystems, highlighting the potential for integrative long-term studies in East Asia (Fig. 1):

1) Pinus yunnanensis forests in southwest China are considered an intermediary stage of succession toward evergreen broad-leaved forest (Tang et al. 2013). However, population dynamics (e.g. to what degree human impact is detrimental to the forest ecosystems) and the factors promoting forest succession (e.g. what drives P. yunnanensis succession?) need to be contextualized in light of long-term ecological changes. The paleodata can shed light on such socio-environmental aspects, acting as a critical asset for identifying best management practices in the wake of environmental changes (Jackson 2007).

2) Low biodiversity patterns across the woodland-steppe ecotone of southern Mongolia are considered to be the result of historical landscape fragmentation (Liu and Cui 2009). Yet, this information needs to be assessed from a longer-term ecological perspective (e.g. Whitlock et al. 2018). This information is critical for understanding the “baseline”, including the nature and degree of which ecological processes (grazing, fire, and other disturbance regime processes) are relevant for maintaining (or affecting) biodiversity in Asian steppe environments.

Workshop participants identified potential management issues that can be addressed by a collaboration between paleoecologists and protected areas members/ stakeholders in Yunnan and conservancy in Mongolia, for instance. In the future, the DiverseK community will continue to build collaborations in terms of publications, project applications, data sharing and field work, based on the networking that was established during the workshop.

The workshop provided a communication and exchange platform for the establishment of sustainable ecosystem management programs in Asia. This DiverseK WG effort has been a step towards enhancing dialogues among policymakers and paleoecology researchers on China's ecosystem management, thereby laying the foundations for future Sino-foreign collaborative research, including attracting early-career and developing-country researchers, to work on all-encompassing sustainable ecosystem management, through the lens of paleosciences.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank PAGES and the National Natural Science Foundation of China for their financial support.

affiliationS

1Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

2Independent researcher, India

3Plant Conservation Unit, University of Cape Town, South Africa

4Peking University, Beijing, China

5Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

6Yuxi Normal University, Yunnan, China

contact

Qiaoyu Cui: qiaoyu.cui igsnrr.ac.cn

igsnrr.ac.cn

references

Colombaroli D et al. (2021) PAGES Mag 29(1): 54

IPCC (2021) Climate Change: The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge

Jackson ST (2007) Front Ecol Environ 5: 455

Liu H, Cui H (2009) Contemp Probl Ecol 2: 322-329

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2023

Past Global Changes Magazine

Potsdam, Germany, 6–10 March 2023, jointly with 2k Network workshop: Hydroclimate synthesis of the Common Era and CVAS workshop: Role of scaling in the future of prediction & emerging themes.

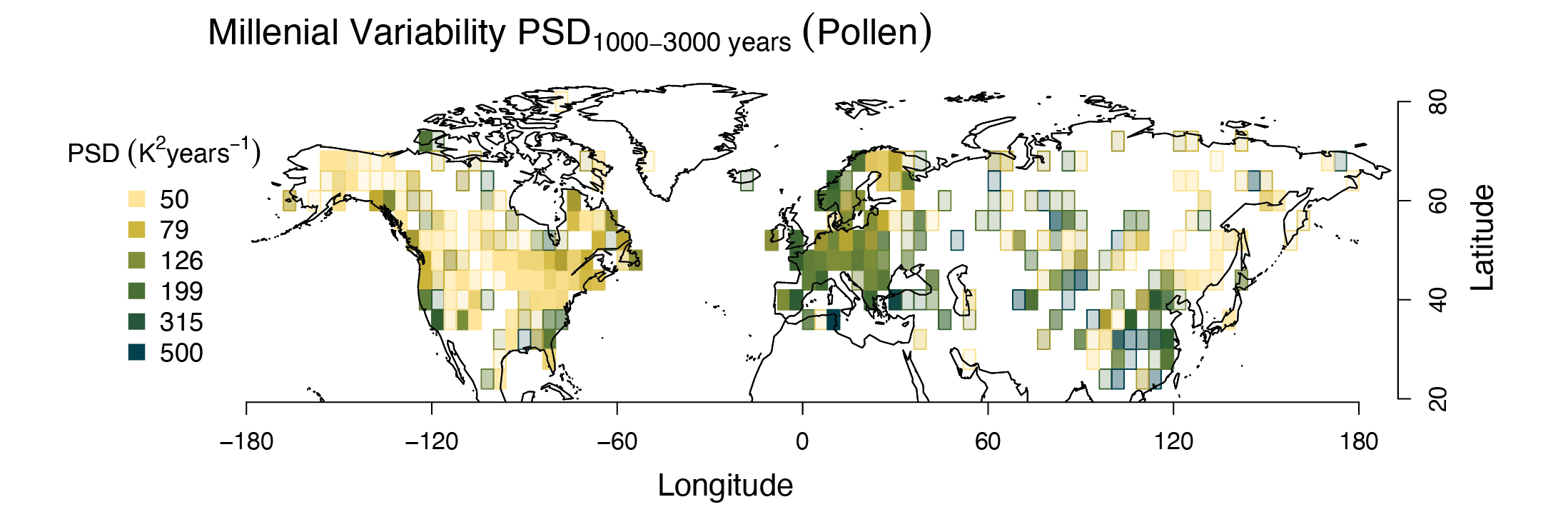

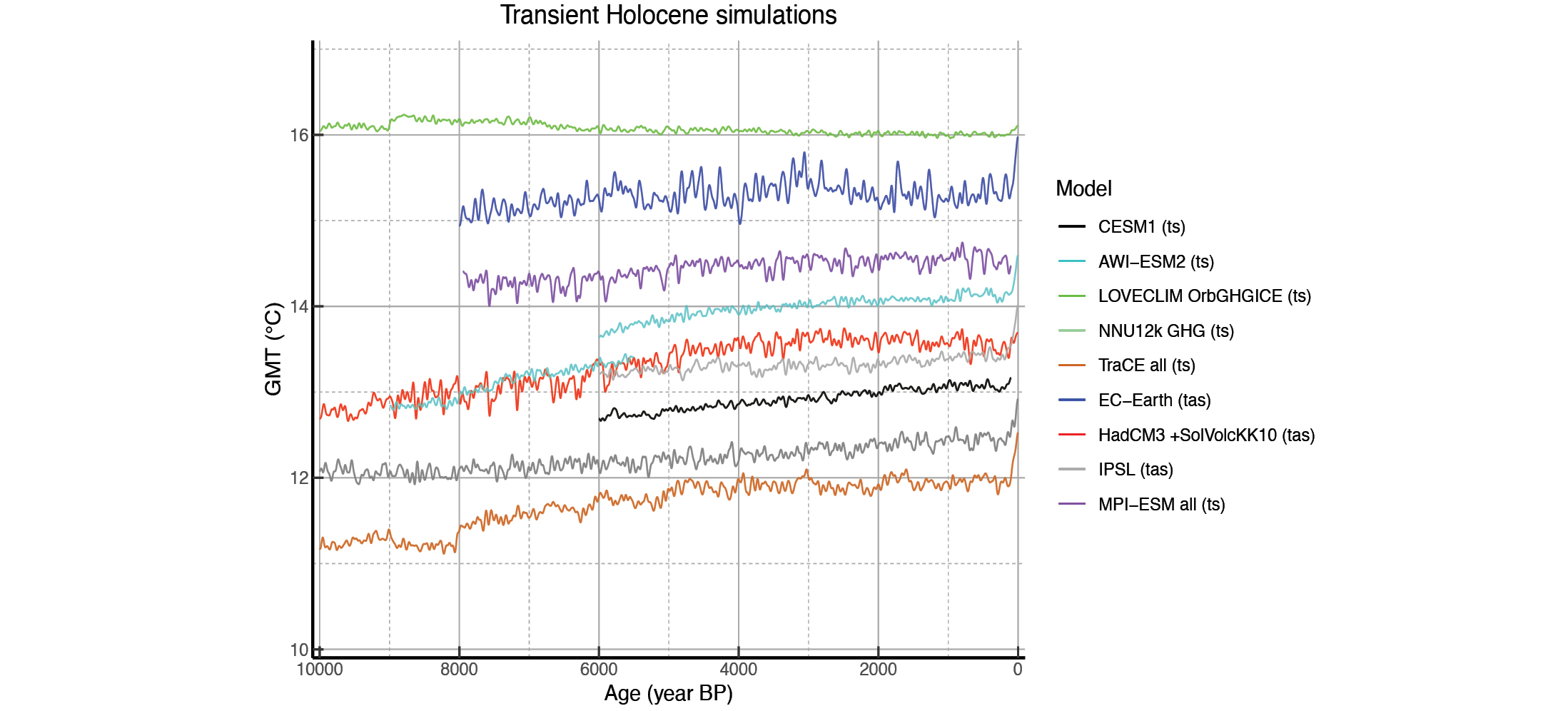

Understanding climate variability is at the heart of climate science and one of the main focus areas of several PAGES working groups (WGs). In particular, the Climate Variability Across Scales (CVAS) WG (pastglobalchanges.org/cvas) and the 2k Network (pastglobalchanges.org/2k-network) use different approaches to understand variability from sub-annual to millennial timescales.

To stimulate deeper interactions between the communities, the two groups gathered in Potsdam, Germany, in March 2023 (pastglobalchanges.org/calendar/134682). The week-long meeting started with individual two-day meetings of the 2k Network and CVAS WGs, discussing hydroclimate variability and climate variability mapping, respectively. Then the two groups joined for a Topical Science Meeting (TSM) on centennial variability. While it is a key timescale, similar to the one of anthropogenic warming, it is less studied and understood than decadal or millennial to multi-millennial timescales. This is partly due to the lack of a significant forcing on this timescale making the expected signal weaker than for glacial–interglacial cycles, for instance. In addition, analyzing centennial variability over the last 2 kyr is associated with many challenges, both on the data and climate modeling sides.

Many proxy timeseries at annual resolution are too short to faithfully reconstruct centennial variations, while longer series may have inadequate resolution or age control. In the meantime, while most climate models simulate some centennial-scale variability, the magnitude, especially regarding surface-temperature variations, is smaller than in proxy-based reconstructions and the spatial patterns vary greatly between models. A TSM on this subject was, thus, an opportunity to review the main issues and prepare actions to make progress on the most critical ones.

The goal of Phase 4 of the 2k Network is to reconstruct and understand hydroclimate variability during the Common Era. The first half of the workshop was used for plenary talks to set the scene for breakout sessions during the second half. An introduction on the history of hydroclimate research within the 2k Network, presented by Thomas Felis, was followed by two talks related to the first goal of the WG: to build a database to reconstruct spatiotemporal hydroclimate variability over the Common Era. Chris Hancock presented work on a Holocene hydroclimate database, and Bronwen Konecky described the process of building the Iso2k database. Seminars by Kira Rehfeld and Nathan Steiger focused on the integration of information from hydroclimate simulations and reconstructions.

The second half of the workshop was used for discussions within the three regional focus groups of Phase 4 to define the research questions and map out pathways towards answering them. The Tropical Pacific and South Asia group identified the reconstruction of ENSO-hydroclimate teleconnections and the variability of large-scale monsoon/circulation patterns as priority targets, whereas the Southern High-Latitude group focused on the reconstruction of extreme hydroclimate events and the understanding of atmospheric blocking events. The North Atlantic group identified large-scale atmospheric modes of variability during climate extremes of the Common Era as a first reconstruction target. All discussions included identifying sources of hydroclimate information, including those not yet in PAGES databases or similar (e.g. x-ray fluorescence [XRF] data), and addressing technical issues related to ensuring adherence to the FAIR data principles to increase interoperability of 2k data products.

The second workshop of Phase 2 of the CVAS project was held to bring together experts using different strategies for climate-related predictions/projections, discuss the possibility of scanning a larger parameter space in climate models and their effect on simulated climate variability, and discuss the progress on the variability mapping. In plenary talks and breakout groups, the experts presented their perspectives on the role of stochastic versus deterministic models and the best way to utilize climate models to improve confidence in climate projections. The discussion highlighted the importance of alternative modeling approaches and looked at first results from scanning the physical parameter space in climate models and its effect on climate variability. The group also prepared the first steps in defining a tuning target for climate models based on paleoclimate proxy data.

For the variability mapping, two groups were formed; one based on proxies calibrated to a physical variable, and one making use of the much larger dataset of proxy records that cannot be directly calibrated (e.g. XRF data). Both groups reviewed the databases to produce global maps of variability and presented their first feasibility experiments. The groups discussed the expected results and the associated hypotheses concerning the spatial structure, scaling, and proxy dependency. Robust patterns from the first mapping attempts concerning centennial temperature variability (such as the relation of variability on proxy type) were identified as input for the TSM workshop.

The 2k Network and CVAS groups then merged for the TSM. An overview of the current state of knowledge confirmed that the climate models reproduce global temperature centennial variability relatively well, related to the response to global forcing, but tend to underestimate the magnitude of regional temperature variations compared to paleoclimatic data, in particular in the tropics. This underestimation has already been suggested at multidecadal timescales in comparisons between model results and instrumental observations covering the past decades and increases when looking at longer timescales (i.e. the underestimation at multicentennial timescales is larger than at multidecadal timescales). While paleo observations indicate that centennial variability is widely present on Earth, the mechanisms leading to centennial variability in models are generally associated with changes in the deep-ocean circulation and deep-water formation, leading to larger amplitude variations largely restricted to the high latitudes. However, even though the changes in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation are at the origin of the centennial variability in many models, the amplitude, origin, and spatial imprint of these changes remain strongly model-dependent. Some show the main changes in the Atlantic and Arctic ocean circulation while others also include more global interactions, including interactions with the Southern Ocean. In contrast, the simulated tropical variability at centennial timescales seems mainly controlled by the strength and response to volcanic forcing.

Based on breakout discussions, the group identified several avenues to pursue to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms responsible for centennial climate variability, and to determine the origin of model-data disagreements:

1) Developing a spatial fingerprint of the centennial variability from both models and data would allow us to test whether the climate variability simulated by climate models is consistent with proxy evidence and, furthermore, learn about the underlying mechanisms leading to variability.

2) Jointly analyzing the hydrological and temperature variability at the centennial scale offers many opportunities to better understand the processes at play by comparing their distinct characteristics.

3) Further studying the Southern Ocean and surrounding continents is particularly needed as centennial variability is observed in many records in the region, but a synthesis of the information provided by the various paleoclimate archives is still lacking.

4) Designing specific numerical model experiments in which strong perturbations are imposed, for instance by increasing the centennial-scale variability of the ocean component to levels deduced from paleoobservations, would enable investigation of the physical consistency of the proxy evidence.

5) Developing a better null hypothesis for significance testing of spectral peaks/oscillations based on a better characterization of the spectral continuum, driven by theoretical understanding and stochastic climate models. This will allow us to jointly study the continuum spectra and oscillations on specific timescales, and better differentiate physical mechanisms underlying centennial variability.

6) Additional work on proxy system models (PSMs) with a focus on the representation of centennial variability is needed to identify the PSMs that should be included routinely in our analyses, and the best way to include them.

Some of those points are already addressed by CVAS (4), the 2k Network (2, 3) or both groups (6), and will be further developed, while new groups were formed to work on the others (1, 5). Information and call for participation will be launched through the PAGES newsletter, but please send an email to the workshop organizers if you awould like to take part in some of the activities immediately.

affiliationS

1Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Potsdam, Germany

2MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences and Faculty of Geosciences, University of Bremen, Germany

3Earth and Life Institute, Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgium

4Exeter College, University of Oxford, UK

5ANU College of Science, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia

contact

Thomas Laepple: tlaepple awi.de

awi.de

references

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2023

Past Global Changes Magazine

14th International Conference on Paleoceanography, Bergen, Norway, and online, 29 August–2 September 2022

The International Conference on Paleoceanography (ICP) has a 40-year-long tradition connecting the global research community that uses marine archives and modeling approaches to reconstruct and simulate the history of the ocean and its role in changing climate. Arranged by the community, this event is held every three years at different locations. In 2022, ICP was arranged for the 14th time (pastglobalchanges.org/calendar/128671), hosted in Bergen, Norway, by the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, the University of Bergen, and NORCE Norwegian Research Centre (Fig. 1). ICP14 brought together 551 researchers from 33 countries (including 175 students) covering all subdisciplines of paleoceanography.

|

|

Figure 1: ICP14 logo inspired by the storage houses of medieval Bryggen in Bergen, the wharf of the Hanseatic League’s trading empire from the 14th to the mid-16th century and the “warming stripes” graphic, first shown by the climate scientist Ed Hawkins at the University of Reading (showyourstripes.info). Image credit: Suet Chan. |

The conference program reflected the diversity of current paleoceanography research and was centred around five themes. In the first theme, “Climate and Ocean Biochemistry”, a focus was set on the reconstruction of biogeochemical cycles, seawater chemistry and elemental cycling in the ocean, factors that are intimately coupled to global climate and marine ecosystems. The second theme, “Ocean Circulation and its Variability”, addressed the state, rate and sensitivity of past ocean circulation and its relationship to climate and carbon-nutrient cycling, while the third theme, “System Interactions and Thresholds”, was dedicated to studies on interactions between the ocean and other Earth system components, and how these interactions generate climate variability across different timescales. This theme also covered ecosystem impacts of changes in the ocean and climate. New insights on the ocean and climate dynamics during past warm climate states were presented under the fourth theme, “Improving our Understanding of a Warmer World”. Finally, the fifth theme, “Innovation to Overcome Knowledge Gaps”, aimed to bring the community up to date on the development of new proxies and approches to reconstruct and model climate change, and enhance our understanding of relevant processes. In addition, focus was set on how to integrate such different approaches to further enhance our understanding of the Earth system.

The conference followed the well-established ICP format: a limited number (28) of invited plenum lectures presented state-of-the-art results and ideas regarding each of the five themes of the conference. Three longer perspective lectures informed of new insights from adjacent research fields that are relevant to paleoceanography. At ICP14, perspective lectures focused on the nitrogen cycle in the mixed layer and its impact on export fluxes, the global overturning circulation, and the role of paleoceanography in the latest IPCC reports. In addition, a keynote talk highlighted advances in the organic geochemistry toolbox. The daily program also included five vibrant plenum discussions on the topics presented each day with all speakers.

The plenary program was complemented by extensive poster sessions allowing for ample discussion time. Poster sessions are the key element of every ICP, where the whole breadth of research is covered. The ICP14 program included 543 poster presentations, among which, 40 were virtual.

For early-career researchers (ECR), ICP contributes to professional development and provides an opportunity to connect with leading scientists, as well as their peers. To support participation of ECRs and scientists from low-income countries, 13 travel and virtual participation grants were provided thanks to funding from ICP13 and PAGES. The outstanding quality of ECR presentations was noted by many of the participants, and three graduate students received a poster award sponsored by PAGES. To facilitate ECR networking, the PAGES Early-Career Network (ECN) organized an open ECR meeting focusing on scientific publishing.

In addition to the scientific program, networking and discussions were facilitated at a range of social activities, another cherished ICP tradition. The social program of ICP14 included the icebreaker, a welcome reception by the City of Bergen in the medieval Håkonshallen, a conference dinner, and the traditional Paleomusicology concert. The concert once again featured excellent and impressive performances by some of the conference attendees.

Outreach activities included an event for high school students by some of the ICP14 attendees and the Bjerknes Centre, strong social media presence, and visits of the Lego Ninja, a Bjerknes Centre local who frequently follows us during fieldwork and other activities (Fig. 2).

|

|

Figure 2: Excerpts from the Lego Ninja story (shorturl.at/CKST2) about its experience at ICP14. Image credit: Petra Langebroek. |

ICP as a hybrid conference and other measures to widen participation

ICP14 was the first ICP to be held in a hybrid format with the aim to allow for participation by those affected by travel restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as those who cannot, or prefer not to, travel for other reasons. In addition, the organizers hoped that the reduced costs for remote participation would allow more colleagues to participate. A digital solution allowed for remote participation of plenary speakers, poster presenters and other participants.

All registered participants had access to the digital poster gallery and were invited to contribute to discussions. The poster gallery was already available prior to the conference and for the two subsequent weeks. This opened opportunities for participants to preview posters, and to also continue visiting posters after the conference. Furthermore, the digital solution allowed for streaming plenary events or watching the recordings at more convenient times.

Given that ICP14 took place at the tail end of the pandemic, and unfortunately some participants fell sick during the conference, the hybrid format allowed speakers and other participants to continue their participation, and, in many cases, prevented the need for last-minute changes. However, while the hybrid format has many advantages, it is important to mention that it leads to a considerable cost increase, for the professional online platform and streaming solutions, and additional conference organization tasks. The community therefore needs to discuss whether the benefits of wider participation options, the added flexibility, and the potential carbon footprint reduction outweigh the extra costs and efforts that are needed.

A survey conducted among ICP14 participants after the conference revealed that the overwhelming majority (85% of 200 respondents) also support hybrid formats for future ICPs, and most respondents (almost 90%) did not mind some of the presentations being given remotely. Those that specified their reasons for online participation did so for various reasons (COVID-19 restrictions, personal reasons, lower costs, other commitments, health), but only few (less than 5%) due to the reduced carbon footprint.

Online posters were seen as added value to the conference by roughly half of the respondents, whereas 23% did not think so. The responses suggest that the online poster gallery was not used to its full potential in this first hybrid iteration of ICP. While about two-thirds of all respondents uploaded a virtual poster, only half of the in-person participants ended up looking at the online posters. Feedback suggested that if virtual-only posters are included (as was the case at ICP14), they should receive more dedicated attention during the meeting (e.g. pitch talk session, dedicated screens, more attention to discussion function for virtual posters).

Feedback on how to broaden participation at ICP included multiple aspects. Regarding speaker selection, most respondents support community nominations of speakers, with the scientific committee making the selection. Many respondents advocated for the importance of diversity in the scientific committee regarding both scientific and non-scientific aspects.

An idea brought up at the conference was the establishment of regional hubs for increasing participation and decreasing carbon footprint, while still allowing for networking. This suggestion was, however, met with varied responses from survey respondents. Around half of the respondents did not have a clear opinion, and the rest were divided into those seeing the positive sides regarding carbon footprint and widening participation in general, while others worry that the hubs would in fact prevent international networking and not help with diversity, equity and inclusion.

Overall, ICP14 was a great success. The community discussion regarding a potential hybrid future for ICP, and other adjustments, should be continued in order to keep this special conference a vibrant, cherished, and welcoming meeting place for the global paleoceanography community.

affiliationS

1Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bergen, Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, Bergen, Norway

2NORCE Norwegian Research Centre, Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, Bergen, Norway

contact

Nele Meckler: nele.meckler uib.no

uib.no

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2023

Past Global Changes Magazine

Décio Muianga1,2,3

Décio Muianga, an archaeologist from Mozambique, visited the University of Mpumalanga in Mbombela, South Africa, as a PAGES Inter Africa Mobility (IAM) Research Fellow. From 1 March to 3 April 2023, he analyzed lithic stone tools recovered from the excavation at Daimane site in southern Mozambique and compared these with stone tool collections from Mpumalanga province to better understand the technocomplexes, and dietary and subsistence changes that occurred during the Middle- and Late Stone Age.

Stone Age archaeological background in Mozambique

Mozambique is located in southeastern Africa and lies between two geographical areas, southern and eastern Africa, where the major developments of human evolution occurred during the Pleistocene and Holocene (Lombard et al. 2012; Mitchell 2012). Evidence of these cultural changes can be found at different sites throughout the country, particularly in southern Mozambique, which is rich in locations with lithics and ceramic remains (Kohtamäki and Badenhorst 2017; Menezes 1999; Muianga 2020; Saetersdal 2004). However, detailed and systematic studies of sequences with well-preserved deposits have not yet been performed. Thus, the Daimane site (Kohtamäki 2014) is a large and intact archaeological sequence that has not been systematically investigated and compared with many open-air sites from diverse chronological periods scattered across the landscape.

Aims of the project

The main objective of the lithic analysis at the University of Mpumalanga was to decipher the rich archaeological record of stone tools and artifacts, contributing to a deeper understanding of human prehistory in the region, and its relevance to the broader narrative of human evolution. The specific research questions whilst at the University of Mpumalanga were:

- What are the key lithic industries and typologies associated with the Middle Stone Age and Late Stone Age in the Lower Lebombo range in southern Mozambique?

- How can the archaeological sequence of the Stone Age deposits of the Daimane shelter, and the association with the surrounding open-air sites, contribute to the chronology of occupation in the area?

Answers to these questions will provide a better understanding of the different early inhabitants of the southeastern tip of Africa, and how the environment influenced the production and changes of the archaeological data recovered from excavations. They will also provide more evidence of lithic development analysis in southern Africa.

Research activities at University of Mpumalanga

The lithic analysis (including typological analysis and microscopic residue identification) of some of the stone artifacts recovered from the excavations in the Daimane II rock shelter was performed at the of University of Mpumalanga laboratory, and supervised by Dr Tim Forssman. These analyses, and comparisons of Stone Age tools (from Mozambique and South Africa), showed some similar typological features, as well as differences, in raw material selection by past hominids. The typological features, and the different technological complexes, were also documented with formal (stone tools used by hominids such as blades, scrapers, segments, etc) and informal (stone debris discarded during the production of formal instruments) tools identified, which correspond to different chronological periods of lithic production by hominids (Fig. 1). Besides the study of the artifacts described above, several sites in rock shelters in the Mpumalanga province were also visited, and large collections of lithics and rock paintings were analyzed for comparative purposes.

|

|

Figure 1: Two lithic tools made out of jasper using the bipolar technique. Photo credit: Décio Muianga. |

Conclusions, outcomes and future plans

The PAGES-IAM Research Fellowship enabled the analyses of parts of the lithic collections from the Daimane II. Lithic analysis has revealed a progressive increase in technological complexity over time, from the Middle Stone Age to the Late Stone Age. This is evident in the development of more refined tool forms, improved raw material procurement strategies, and enhanced manufacturing techniques. Another aspect the analysis revealed is the diversity of geological raw materials identified, not only in the excavated materials corresponding to the Middle-to-Late Stone Age transition, but also during the period of economy based on hunting and gathering, which continued until the 1800s in Mozambique and South Africa. Four publications about different aspects of the current research are currently in preparation, and they will be submitted to peer review journals.

The evidence of this complex process of occupation is well preserved in the archaeological deposits of the Daimane rock shelter. Thus, more chronological dating (e.g. radiocarbon, phytoliths, optically stimulated luminescence) and mineralogical analysis of the ceramics, and faunal remains analysis are underway. These results will bring forth a key contribution to understanding the long sequence of the Daimane site.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to Dr. Tim Forssman and to all the staff members and students who made my stay enjoyable during the four weeks in the laboratory, and while visiting the sites in Mpumalanga.

affiliationS

1Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University Eduardo Mondlane, Maputo, Mozambique

2Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University, Sweden

3Kaleidoscopio, Maputo, Mozambique

contact

Décio Muianga: decio.jose uem.mz

uem.mz

references

Kohtamäki M (2014) PhD Thesis, Uppsala University, 169 pp

Kohtamäki M, Badenhorst S (2017) South African Archaeo Bull 72: 80-90

Lombard M et al. (2012) South African Archaeo Bull 67: 123-144

Menezes MP (1999) PhD Thesis, The State University of New Jersey, 793 pp

Mitchell P (2012) South African J Sci 108 (11-12): 1-2

Muianga DJD (2020) Lesedi 23: 60-63

Saetersdal TW (2004) PhD Thesis, University of Bergen, 331 pp

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2023

Past Global Changes Magazine

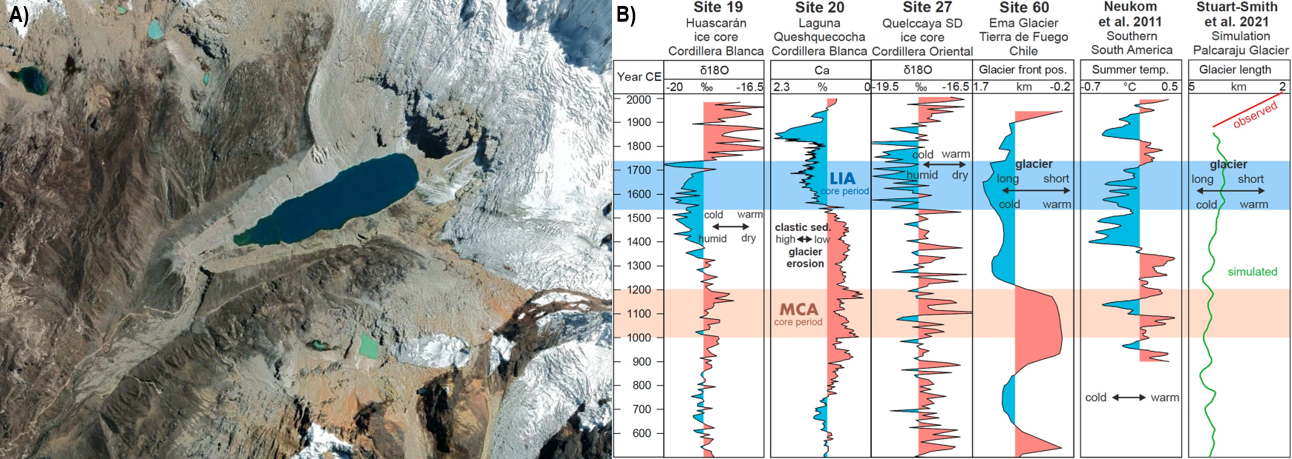

Dr. Cinthya Bello, from Perú, visited Centro Universitario Regional Este (CURE) - Universidad de la República de Uruguay as a PAGES-IAI (Inter-American Institute for Global Change Research) Mobility Research Fellow. From 12 March to 8 April 2023, she strengthened her knowledge in the application of paleoenvironmental science as a complementary tool to ongoing glaciological modeling for the reconstruction of past glacial environments.

An overview: periglacial system in the Peruvian Andes

The tropical Andes have been negatively impacted by hydroclimatic and socioeconomic changes in the context of global change (Drenkhan et al. 2018). In the Peruvian Andes, glaciers show significant ice loss equivalent to 1284.95 km² (53.56%) between 1955 and 1962, and during 2016 (INAIGEM 2018). In addition, recent studies confirmed the development of several high mountain lakes, as a result of glacier shrinkage (Colonia et al. 2017), which increase the glacial-lake outburst flood hazards (GLOFs). Despite the effort to develop an inventory and projection of future lake formation in the Peruvian mountain ranges, there is a lack of knowledge regarding the evolution of these periglacial systems. It is necessary to comprehensively assess their past, present, and future development under climate change scenarios to ensure sustainable water use. Therefore, paleolimnology represents a useful tool for studying periglacial systems because this interdisciplinary science uses chemical, physical, and biological information from the sedimentary record to reconstruct the environmental evolution of these systems on a millennial, secular, decadal, and interannual timescale (García-Rodriguez et al. 2009).

Thanks to the support of the PAGES-IAI Fellowship, I participated in a series of lectures dedicated to an overview of the different techniques used in paleolimnology in order to: 1) reconstruct the evolution of glacier lake systems; 2) analyze sediment cores with a multi-proxy approach for environmental reconstructions (e.g. lithology, geochemistry, dating); 3) use software for data handling, importing data and visualization (e.g. PAST, BACON); and 4) learn new approaches for the historical reconstruction of paleoenvironments (e.g. faunal remains).

In addition, the article written by Stuart-Smith et al. (2021) was discussed. This study describes a rapid expansion of the Lake Palcacocha (Fig. 1a) since the pre-industrial era, located in the city of Huaraz (department of Ancash, Perú), due to the retreat of the Palcaraju Glacier driven by the anthropogenic increase of temperature by 1°C since 1880 CE. However, Lüning et al. (2019, 2022) has also demonstrated that Andean glaciers retreated significantly during the Medieval Climate Anomaly (1000–1200 CE), a warm climate period in South America, and questioned the conclusions by Stuart-Smith et al. (2021). This disagreement reveals a clear lack of a coherent network of paleoenvironmental data that represents a weakness in paleoenvironmental research (Fig. 1b).

Therefore, as part of this fellowship, a multidisciplinary group comprising researchers from Uruguay, Brasil and Perú prepared a research proposal with the aim of undertaking a paleolimnological study in the periglacial Lake Palcacocha in order to reconstruct the environmental variability over the last 2000 years. In addition, the proposal aims to improve the projections of climate models, and reconstruct the mass balance of Peruvian glaciers by using artificial intelligence algorithms and data from global climate models and reanalysis, such as CMIP6 and ERA5, respectively. Furthermore, our collaborative project will strengthen the academic relationship between Peruvian, Brazilian and Uruguayan research universities, promoting studies about paleoenvironmental reconstruction using paleolimnological methods to improve ecosystem management and conservation plans.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PAGES-IAI International Mobility Research Fellowship Program for Latin American and Caribbean early-career scientists on past global changes.

affiliationS

1Carrera de Biología Marina, Universidad Científica del Sur, Lima, Perú

2Programa Doctoral en Recursos Hídricos, Universidad Nacional Agraria la Molina, Lima, Perú

3Dirección de Asuntos Antárticos, Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, Lima, Perú

4Centro Universitario Regional Este, Universidad de la República, Rocha, Uruguay

5Instituto de Oceanografia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande, Brazil

contact

Cinthya Bello: cbelloc cientifica.edu.pe

cientifica.edu.pe

references

INAIGEM (2018) Informe de la situacion de los glaciares y ecosistemas de montana. Huaraz

Colonia D et al. (2017) Water 9(5): 336

Drenkhan F et al. (2018) Glob Plan Change 169: 105-118

García-Rodríguez F et al. (2009) PAGES News 17: 115-117

Lüning S et al. (2019) Quat Int 508: 70-87

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2023

Past Global Changes Magazine

Aster Gebrekirstos1,

H.G. Gracias2,

J. Ngoma3,

M. Mokria4,

L.H. Balima5,

S. Kapoury6,

A. O. Patrick7 and

E. A. Boakye8

H.G. Gracias2,

J. Ngoma3,

M. Mokria4,

L.H. Balima5,

S. Kapoury6,

A. O. Patrick7 and

E. A. Boakye8

Tree-ring-based proxies have been widely used in ecology and climate change studies for centuries (Fritts 1976), particularly in temperate regions. As trees grow, changes in environmental factors are recorded in the wood produced during specific time periods. Consequently, trees are key terrestrial archives, providing reliable insights into past climate and environmental variability on a year-by-year basis at local to regional scales, given that they can form annual rings and grow for hundreds of years (Fig. 1).

|

|

Figure 1: Baobab tree from Western Tigray (Ethiopia) that can grow for hundreds of years. Photo credit: Aster Gebrekirstos. |

Tree rings enable the use of precise dating methods, and provide high-resolution paleoenvironmental information through different proxies. With the development in technology, tree rings are also important indicators of plant physiological responses to changing climatic conditions and for further understanding of long-term ecological and hydroclimatic processes. Given the versatility of dendrochronology, and the diversity of environmental questions that can be addressed, the field continues to grow with new frontiers and advances in technology. Methods that are applied to decode minutes, decades to multi-centuries of information include tree-ring analysis, wood anatomy, stable isotopes and dendrometers. The results provide insight into current and past climate and environmental variability at seasonal and annual resolution, and from local to regional scales. Tree-based information, therefore, elucidates climate change impacts on tree growth and provides evidence and data to help understand long-term climate and ecological processes (Gebrekirstos et al. 2014)

Scientific goals and objectives

Many livelihoods, economic activities and energy sources in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are largely dependent on climate-sensitive natural resources. The climate crisis is increasing the frequency and intensity of floods, droughts, and heatwaves, with Africa expected to be among the global regions hit hardest (Tzachor et al. 2023). As climate impacts continue to negatively affect the population, economy and ecosystems in Africa, there is a need to increase scientific and research capacity and facilities on the continent. Establishing the African Tree Ring Network (ATRN) working group (WG) (pastglobalchanges.org/ATRN) is, therefore, an opportunity to advance the use of tree rings in the tropics, particularly in Africa in the fields of, for instance, paleoecology/hydroclimatology, forestry/agroforestry, biodiversity, ecophysiology, and restoration ecology, as a new frontier.

In recent years, dendrochronology in Africa has experienced a rapid expansion and is beginning to fill important gaps in existing tree-ring based data that is dominated almost exclusively by temperate regions (Gebrekirstos et al. 2014; Zuidema et al. 2022). For instance, based on tree-ring widths in Juniperus procera in Ethiopia, Mokria et al. (2017) reconstructed hydroclimate variability over the past 350 years. Gebrekirstos et al. (2009) also characterized co-occurring savanna species into opportunist and resilient species based on their response to rainfall variability.

A combination of tree-ring width and stable isotopes are also used to address questions related to water-resource management, agroforestry and climate-forest management feedbacks. For example, these techniques have been used to reconstruct changes in surface hydrology (Mokria et al. 2018), to determine which species is more productive, resilient and drought tolerant (Gebrekirstos et al. 2009), which species sequester more carbon (Sanogo et al. 2016), and to better quantify the carbon sequestration by tropical trees and forests (Zuidema et al. 2022). Yet this science is the least developed on the globe.

The main scientific objective of this WG is, therefore, to bring together African tree ring scientists and take stock of the development in terms of science, methods, data, human capacity, and facility on the continent. We will analyze the challenges and opportunities to advance tree-ring-based science in different environments and climate zones across the continent. We will provide improved methods, approaches, and best practices to enable cross-regional data analysis and synthesis to support informed decision-making on pressing environmental questions and climate issues, considering the diverse effects on African ecosystems.

We will organize meetings and workshops, field training, and citizen science initiatives to increase awareness in collaboration with international and regional partners, policy makers, and donors. We will also create a link between the tree ring, modeling, and multi-proxy communities to develop a vibrant network and advance scientific capacity in the continent, and beyond.

Upcoming activities

Visit the ATRN website at pastglobalchanges.org/ATRN and sign up to the mailing list for all information, news and activities. Send us an email to become a member of the ATRN working group.

affiliationS

1CIFOR-ICRAF, Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry, Nairobi, Kenya

2Faculty of Agronomic Sciences, University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin

3The Copperbelt University, Department of Biomaterials Science and Technology, School of Natural Resources, Kitwe, Zambia

4CIFOR-ICRAF, Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

5Laboratory of Plant Biology and Ecology, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

6Institut d'Economie Rurale (IER), Point Focal de la biodiversité des ressources génétiques pour l'alimentation et l'agriculture, CRRA-SOTUBA, Bamako, Mali

7Osun State University, Osogbo, Nigeria

8Working Group on Forest Certification, Kumasi, Ghana

contact

Aster Gebrekirstos: a.gebrekirstos cifor-icraf.org

cifor-icraf.org

references

Fritts HC (1976) Tree Rings and Climate. Academic Press, 582 pp

Gebrekirstos A et al. (2009) Glob Planet Change 66 (3-4): 253-260

Gebrekirstos A et al. (2014) Curr Opin Environ Sustain 6: 48-53

Mokria M et al. (2017) Glob Change Biol 23: 5436–5454

Mokria M et al. (2018) Quat Sci Rev 199: 126-143

Sanogo K et al. (2016) Dendrochronologia 40: 26-35

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2023

Past Global Changes Magazine

Marine diatoms (Bacillariophyceae) are the most important primary producers in the world’s oceans and are highly sensitive to changes in their environment (e.g. sea-surface temperature, salinity, and sea ice). Additionally, diatoms have a high species diversity, a well-known morphological classification, and their fossilized valves, which are made of silica, generally preserve well in sediments.

Due to these features, diatoms have been widely used as a paleoceanographic proxy for reconstructing past sea-surface conditions (Koç Karpuz and Schrader 1990). Diatoms have been used for both qualitative and quantitative reconstructions, which are often based on surface-sediment datasets. These datasets include information on diatom assemblages, as well as data on ocean-surface conditions (e.g. temperature and salinity) at each sampling site.

Multiple diatom surface-sediment datasets have been created for the Arctic region (e.g. Caissie 2012; Krawczyk et al. 2017; Miettinen et al. 2015; Ren et al. 2014; Sha et al. 2014). However, these datasets have been built using slightly different methodologies and diatom taxonomies. This can have an influence on the final reconstruction, depending on which dataset is used. Additionally, training sets are a valuable tool for understanding the autoecology of individual species (Oksman et al. 2019), which is essential for the robustness of both quantitative and qualitative reconstructions.

The Marine Arctic Diatoms (MARDI) working group (WG) aims to bring together diatomists working with paleoceanographic reconstructions, to align diatom taxonomy across different Arctic diatom datasets, and to unify the used methodologies in diatom-sample preparation.

Scientific goals and objectives

MARDI aims to improve the precision and reliability of diatom-based paleoceanographic reconstructions in the Arctic and sub-Arctic areas. The WG launched in November 2022 and during its first months gathered 11 diatom surface-sediment datasets from (sub)Arctic regions, including over 1300 surface-sediment samples (Fig. 1).

|

|

Figure 1: Map of the location of the surface-sediment samples with diatom floral data (purple dots) in the Arctic region (n>1300). |

The MARDI WG will align and harmonize diatom taxonomies in the datasets and integrate them into an open-access pan-Arctic database. MARDI aims to advance the use of quantitative diatom transfer functions, as well as develop new semi-quantitative approaches. Furthermore, the WG aims to bring together Arctic marine diatomists to agree on community-wide protocols for the preparation of diatom samples.

Harmonization of Arctic diatom taxonomy was initiated during the second MARDI workshop: “Harmonisation of (sub)Arctic diatom taxonomy” (p. 126) held from 6–8 June in Helsinki, Finland. The workshop brought 17 participants from 10 countries together to discuss issues in Arctic diatom taxonomy and methodology.

Upcoming activities

The next MARDI activities will include a series of mini-workshops focusing on the challenging diatom taxa identified during the taxonomic workshop. These one-day workshops will be organized in the upcoming months and will be held online, where each workshop will have a focus on one species.

The next in-person workshop will be held in June 2024 in Aarhus, Denmark. This workshop will focus on the statistical relationship between species and environmental variables, and on improving the robustness of quantitative reconstructions. Finally, a summer school has been planned for June 2025 in the USA (Iowa Lakeside Laboratory) and will be specifically targeted to early-career researchers.

Visit the MARDI website at pastglobalchanges.org/mardi and sign up to our mailing list to receive news and updates on our activities.

affiliationS

1Environmental Change Research Unit, Ecosystems and Environment Research Programme, University of Helsinki, Finland

2Department of Glaciology and Climate, Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Copenhagen, Denmark

3Department of Earth Sciences, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, Canada

4Geology, Minerals, Energy, and Geophysics Science Center, United States Geological Survey, Menlo Park, USA

5University of California, Santa Cruz, USA

6Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, Denmark

contact

Tiia Luostarinen: tiia.luostarinen helsinki.fiabraham.dabengwa

helsinki.fiabraham.dabengwa wits.ac.za

wits.ac.za

references

Caissie BA (2012) PhD Thesis. University of Massachusetts Amherst, 213 pp

Koç Karpuz N, Schrader H (1990) Paleoceanography 5(4): 557-580

Krawczyk DW et al. (2017) Paleoceanography 32: 18-40

Miettinen A et al. (2015) Paleoceanography 30: 1657-1674

Oksman M et al. (2019) Mar Micropaleontol 148: 1-28

Ren J et al. (2014) Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 402: 81-103

Sha LB et al. (2014) Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 403: 66-79