- Home

- Taxonomy

- Term

- PAGES Magazine Articles

PAGES Magazine articles

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2012

PAGES news

John Dearing and Peter Langdon

Geography and Environment, University of Southampton, UK; J.Dearing soton.ac.uk

soton.ac.uk

New Forest, UK, 4-6 January 2012

The annual discussion meeting of the Quaternary Research Association was held in the picturesque, winter landscape of the New Forest National Park in southern England. The overall theme of the meeting was “Quaternary Science and Society” and it proved to be popular, attracting over 100 attendees. The PAGES-Focus 4 sponsored open sessions “Human-climate-ecosystem interactions: learning from the past” took up four of the 10 sessions. PAGES helped to support eight early career researchers from Australia, Romania, the USA, and the UK to attend the Focus 4 sessions. The Focus 4 presentations were split into several groups. One group focused on the response of past human societies to climate change as reconstructed linking archeological and paleoecological data. Within that group Andy Dugmore (Edinburgh, UK) showed how resilience theory could be combined with detailed and interdisciplinary studies of past communities across the North Atlantic to explain the reasons for either social collapse or long-term sustainability. Michael Grant (Wessex, UK) described how the past trajectories of woodland species in the local New Forest were providing insight into modern day management of the woodlands. One of the PAGES-supported early-career researchers, Giri Kattel (Ballarat, Australia), used paleolimnological data to assess human-climate-ecosystem linkages illustrating how sediments in maar (crater) lakes could be used as recorders of climate regime shifts and to study adaptability of past ecosystems.

A second group of papers were methodology-centric with reports on the development of isotopic and bimolecular analyses, and on approaches to translate pollen records into land use cover. Virgil Dragusin (Bucharest, Romania) explored possible human-environment interactions during the Bronze and Iron Ages in SW Romania as recorded by carbon stable isotopes in speleothems. Joseph Williams (Kansas, USA) was drawn to the discussion of novel approaches in environmental and biodiversity change, such as the ongoing development of plant biomarkers and ancient DNA analysis. Hazel Reade (Cambridge, UK) assessed the paleoclimatic interpretation from the isotopic analysis of tooth enamel with regard to the archeological record of Northeastern Libya.

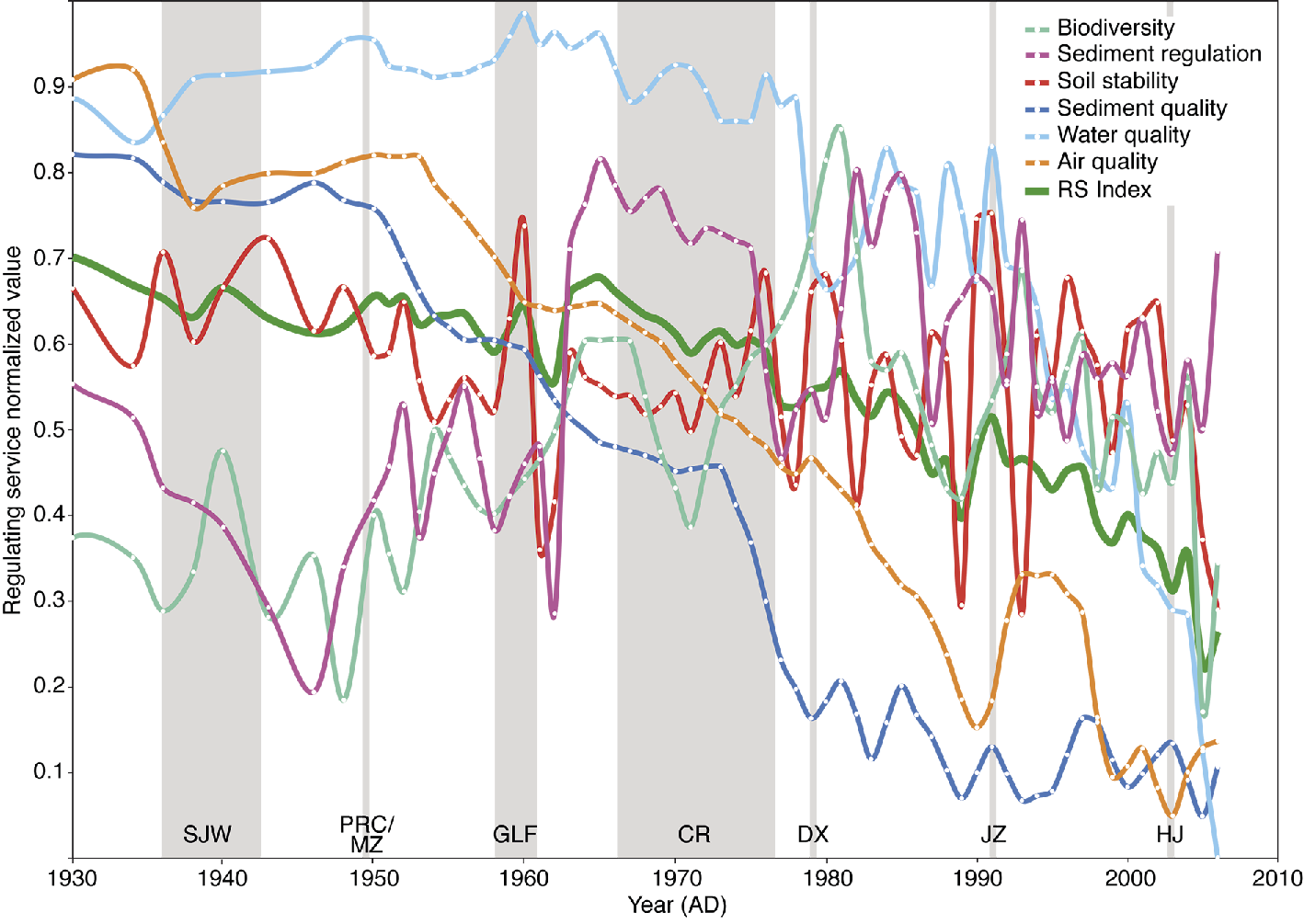

A third group linked paleoenvironmental studies to past and present socio-ecological resilience. Using multiproxy records, this group of studies revealed long-term interactions between climate, human activities and ecosystem services, the presence of thresholds and early warning signals, and reference conditions for conservation. Zhang Ke from Southampton (UK) shed light on recent attempts to use paleoenvrionmental records as proxies for ecosystem services in the lower Yangtze basin (Fig. 1). The paper by Wang Rong (Southampton, UK) examined the evidence for early warning indicators of eutrophication in lake sediments from southwestern China. And Helen Shaw (Lancaster, UK) assessed paleoecological and historical contributions to understanding sustainability, resilience, and ecosystem services within traditional pastoral management. The wide range of questions that were addressed across many geographical zones, served to emphasize the growing use of paleoenvironmental archives to understand human-environment interactions. Reflections on the meeting by recipients of PAGES support gave a flavor of the intellectual atmosphere and rapport generated during the meeting. One recipient commented that the meeting was timely: taking place not only when ecosystems are increasingly threatened by rapid climate change and human activities but when scientific communities across the globe are trying to find the best possible approaches to mitigate these effects. This meeting was a significant step toward our efforts for a comprehensive understanding of the human-climate-ecosystem interactions during the 21st century that help promote societal and ecosystem resilience against future climate change. The use of a range of proxy indicators to understand ecosystem response to climate and human drivers can help us develop not only management tools but also our theoretical understanding of ecosystem responses to multiple and complex forcing.

references

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2012

PAGES news

|

Gavin A. Schmidt1 and Valérie Masson-Delmotte2, Co-Chairs

1NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, New York, USA; gavin.a.schmidt nasa.gov

nasa.gov

2Institut Pierre Simon Laplace and Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement, Gif-sur-Yvette, France

WCRP, Denver, USA, 28 October 2011

Since 1999, the PAGES/CLIVAR (Climate Variability and Predictability) Intersection Panel (www.clivar.org/organization/pages) has focused on benefitting from the combined expertise and insights of scientists working on modern climate observations and processes and those collecting and interpreting paleoclimate records.

The World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) Open Science Meeting in Denver, USA, in October 2011, featured many examples of paleoclimate information being used to extend the instrumental record, evaluate climate models, and place modern changes in a longer-term context. It was therefore an excellent backdrop for the annual committee meeting of the Intersection Panel.

Our Panel meeting was dedicated to finding the best strategies for boosting collaborations across the WCRP “seamless” community (not just CLIVAR). Panel member rotation was addressed with an objective of ensuring a wide range of interests and geographical spread in new members. This selection is now underway, and any readers interested in joining the panel are encouraged to contact the chairs.

Links with other panels and working groups were also an important topic of discussion. Representatives from the Global Monsoon working group, CLIVAR Atlantic panel, and others expressed great interest in increasing the paleo-climate component in their discussions and projects. In particular, the PAGES Ocean2K synthesis project (http://pastglobalchanges.org/science/wg/2k-network/former-2k-activities/regional-2k-groups/ocean2k/intro) (motivated by our Panel thanks to CLIVAR Scientific Steering Committee inputs) that focuses on bringing together high-resolution ocean proxy data for the last two millennia was highlighted as an important bridge to the observational oceanographic community. The Panel has instituted a new mailing list (clivar-pages-open clivar.org) that we hope will be a resource for notifications of cross-cutting projects and workshops, and a platform for ideas on how to engage wider community participation. To subscribe, please go to www.clivar.org/clivarpages-mailing-list.

clivar.org) that we hope will be a resource for notifications of cross-cutting projects and workshops, and a platform for ideas on how to engage wider community participation. To subscribe, please go to www.clivar.org/clivarpages-mailing-list.

The centerpiece of discussion at the meeting was the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5) and database. For the first time within the CMIP protocol, paleoclimate simulations for the Last Glacial Maximum (21 ka ago), mid-Holocene (6 ka ago) and last millennium (Paleoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project, PMIP3) have been included alongside historical simulations for the 20th century and future projections. This allows for a much greater analysis of whether and how paleoclimate model/data comparisons are informative of future projections.

The Panel organized a workshop focused on this topic in March 2012 (Schmidt et al., this issue), and the outcomes were presented to the wider CMIP5 community. The Panel is working to produce a refereed ”white paper” on the best practices for using the PMIP3 simulations to help constrain projections. The white paper will address issues of statistical robustness, dataset synthesis, comparison strategies and quantification of uncertainties due to the model structure, data set uncertainty and forward modeling approaches.

Overall, this is an exciting time to be bringing these communities together, and the resulting new initiatives have enormous potential.

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2012

PAGES news

|

Gavin A. Schmidt1, E. Guilyardi2,3, M. Kageyama4, M.E. Mann5, V. Masson-Delmotte4 and A. Timmermann6

1NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, New York, USA; Gavin.A.Schmidt nasa.gov

nasa.gov

2Laboratoire d’Océanographie et du Climat, Institut Pierre Simon Laplace, Paris, France

3Department of Meteorology, University of Reading, UK

4Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement, Institut Pierre Simon Laplace, Gif-sur-Yvette, France

5Department of Meteorology, Pennsylvania State University, USA

6Department of Oceanography, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, USA

PAGES-CLIVAR Workshop, Honolulu, Hawaii, 1-3 March 2012

The Bishop Museum in Honolulu, Hawaii, provided a picturesque backdrop to the PAGES-CLIVAR Intersection Panel workshop. The main objective of the workshop was to bring together modelers, theoreticians and paleoclimatologists to commence analysis of results from Phase 5 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5) simulation database. The CMIP5 project is a community-wide effort to provide standard protocols for climate model simulations covering the historical instrumental period, future projections and a number of idealized simulations to aid the understanding, detection and attribution of climate change. Significantly, and for the first time, there is a concurrent paleoclimate component, in collaboration with the Paleoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project Phase 3: PMIP3, that uses the same models for three specific experiments covering the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, 20 ka ago), the Mid-Holocene (MH, 6 ka ago) and the Last Millennium (a transient simulation from 850 to 1850 AD; Taylor et al. 2012).

Comparisons of paleoclimate simulations and proxy observation have a long history via earlier incarnations of PMIP and many individual studies, which motivated comprehensive data syntheses. However, it has been a challenge to quantitatively link the future simulations with skill or sensitivity in the paleoclimate simulations. There are a number of reasons for this, not least because paleo-simulations were often not performed with the same models being used for future projections and through a lack of suitable paleoclimate metrics; predominantly large scale syntheses of the proxy data. The workshop focused specifically on this missing step – to make the quantitative connections, so that paleo-climate can become demonstrably useful for constraining future projections.

The workshop began with a comprehensive discussion on the nature of the multi-model ensemble of opportunity and the techniques available for assessing model skill. The evidence indicates that the current models don’t differ in kind from previous efforts (and so previous work can be analyzed in the same framework) and that there is sufficient reason to expect that, particularly for the LGM, the model spread likely encompasses the observations. However, it was widely acknowledged that it is challenging to find diagnostics of the models which can be compared to paleoclimate observations and that also correlate to model projections of the future. The remainder of the workshop was focused on specific uncertainties highlighted in IPCC AR4 for which there are some clear indications that paleo-climate might help. These included patterns of regional rainfall, temperature seasonality, climate sensitivity, ocean-atmosphere modes in the tropical Pacific, the response of the North Atlantic Meridional Circulation, and spectra of climate variability.

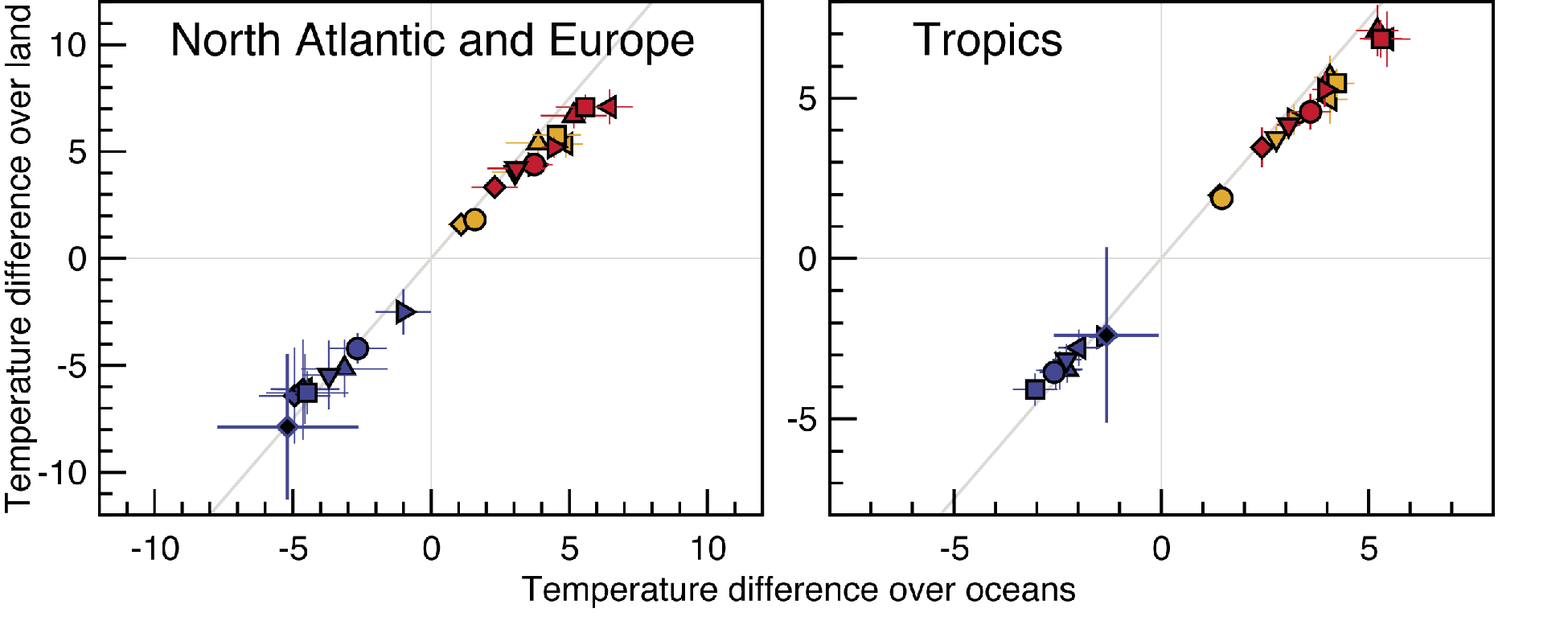

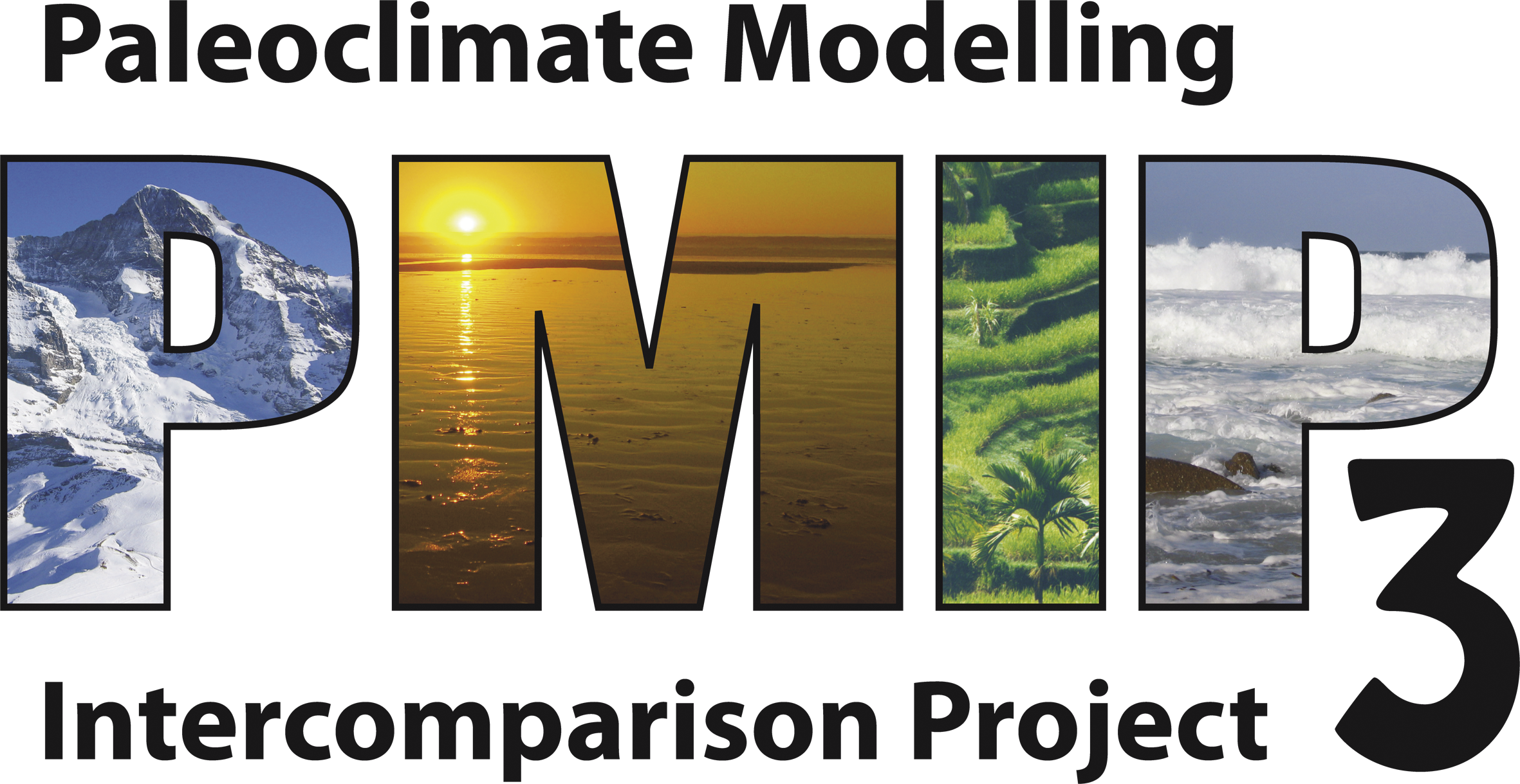

Assessments of climate sensitivity using the LGM are very promising, with a large increase in available and relevant simulations over PMIP2. In the preliminary data there appears to be a correlation of verifiable temperature patterns at the LGM to future projections (Fig. 1). Large-scale changes in rainfall patterns are also very promising targets, with a clear coherence of tropical rainband shifts in latitude as a function of equatorial SST gradients across all the model simulations. Ocean circulation metrics – whether for the overturning circulation or the spectral character of tropical Pacific ocean-atmosphere dynamics including El Niño/Southern Oscillation – are not quite at the same stage due to a lack of sufficiently constraining proxies, and continuing uncertainty of the sampling biases arising from the short time over which modern observations have been collected.

Figure 1: Preliminary results from the CMIP5 archive showing the multi-model ensemble for temperature differences at the LGM and in idealized increased CO2 experiments. Left-hand panel shows the robust relationship between the North Atlantic and European ocean and land temperatures in both cold and warm climates (using an average of the simulation data over points only where there are observations). Right hand panel shows equivalent results for the Tropics. The blue crosses indicate the results (with uncertainties) from the observational data syntheses from the LGM. Red and yellow symbols show the CMIP5 model results. Figure courtesy of Masa Kageyama.

Participants at the workshop are working on a full white paper describing the approaches that can be taken and highlighting the preliminary results, but one conclusion is already clear: paleo-climate simulations have come of age as part of the suite of evaluations any model must undergo.

references

Taylor KE, Stouffer RJ, Meehl GA (2012) Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 93: 485-498

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2012

PAGES news

|

Michal Kucera, A. Paul and S. Mulitza

MARUM - Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, Germany; mkucera marum.de

marum.de

PMIP-MARUM-PAGES Workshop on Comparing Ocean Models with Paleo-Archives 2012 (COMPARE 2012) – Bremen, Germany, 18-21 March 2012

Comparisons of model simulations with data on the state of the ocean in the past are frequently used to study climate processes under different boundary conditions and to understand climate and ocean change in Earth history. Such approaches can be used to benchmark climate models and model ensembles (Hargreaves et al. 2011). They hold considerable promise in demonstrating the ability of climate models to simulate the response to changes in forcing factors (Braconnot et al. 2012) and to help constrain critical parameters, such as climate sensitivity (Schmittner et al. 2011).

The Phase 3 of the Paleoclimate Modelling Intercomparision Project (http://pmip3.lsce.ipsl.fr), which is the paleo-component of the fifth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (http://cmip-pcmdi.llnl.gov/cmip5), is currently being completed with a number of new model run results. For the first time, the paleoclimate simulations use the same model setups as those used for projecting future climate. One of the goals of PMIP3 is to examine climate predictability and to determine why similarly forced climate models produce a range of climate responses. To this end, the PMIP3 model runs have to be confronted with paleodata for the time intervals that have been modeled. Among these are the last glacial maximum (LGM), but also the last interglacial, the early Holocene, and the last deglaciation. For this comparison, marine sedimentary data will play a crucial role, because of their precise and consistent dating, and the fact that they record regionally representative patterns in key modeled variables, which can be reconstructed quantitatively (e.g. Lynch-Stieglitz et al. 2007; MARGO 2009).

Considering the wealth of existing proxy data on the state of the past oceans and the imminent release of the new PMIP3 paleoclimate simulations, the scientific community became convinced that the upcoming data-model comparisons would benefit from the joint expertise of modelers and paleoceanographers. Joint initiatives potentially include working towards innovative statistical methods, quantifying uncertainty, and making the most of proxies for parameters besides sea surface temperature. With this in mind, the COMPARE 2012 meeting was conceived as a joint initiative of PMIP3, PAGES and MARUM. Over 40 scientists from nine countries assembled in Bremen to work towards establishing the union between paleo-ocean data and model simulations. The first half of the workshop was dedicated to presenting the latest model results of the status of paleo-ocean data and emerging new approaches for combining the two, including inverse methods (Fig. 1) and forward modeling of proxies.

The workshop culminated in splinter meetings of three task groups that brainstormed the main issues that arose from the initial discussions: how to best deal with data uncertainty, how to quantify model data misfit and model error, and what the potential benefits and challenges are to working with non-traditional variables, time slices and transients. A number of individual projects, including an ocean data synthesis for the 6 ka time slice, were set up. Besides this, the workshop delivered important take-home messages: A thorough consideration of uncertainty is essential for a meaningful data-model comparison; a dialogue between data and modeling communities is important in finding most useful ways of evaluating model results; multi-proxy information adds complexity to data but helps reveal uncertainties that would otherwise have gone unnoticed; and future data-model comparisons need to be quantitative and “intelligent” (diagnostic, process-oriented). The complexity of handling multiple sources of uncertainty in proxy data (proxy attribution, age model) calls for the development of a data portal or interface allowing an interactive access to large datasets, their on-line handling and visualization.

references

Braconnot P et al. (2012) Nature Climate Change 2: 417-424

Hargreaves JC et al. (2011) Climate of the Past 7: 917-933

Lynch-Stieglitz J et al. (2007) Science 316: 66-69

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2012

PAGES news

|

Daniel J. Hill1,2, A.M. Haywood1, D.J. Lunt3, B.L. Otto-Bliesner4, S.P. Harrison5 and P. Braconnot6

1School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, UK; d.j.hill leeds.ac.uk

leeds.ac.uk

2Climate Change Group, British Geological Survey, Nottingham, UK

3School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, UK

4Climate and Global Dynamics Division, National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, USA

5Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

6Laboratory for Climate and Environmental Sciences, Pierre Simon Laplace Institute, Gif-sur-Yvette, France

2nd PMIP3 General Meeting, Crewe, UK, 6-11 May 2012

Past climates provide an opportunity to examine the working of the Earth system under a much wider range of forcing than those experienced during the historical period. The Paleoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project (PMIP) is an ongoing program tasked with the systematic comparison of models and observations of past climate. Over the last 20 years, through the definition of model experimental designs and the syntheses of paleoenvironmental data, PMIP has made significant progress in the understanding of a number of key periods of the past. Previous PMIP experiments have included the mid-Holocene (MH) and the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). For the latest iteration, PMIP3, the last millennium (LM), the Eemian (last interglaciation) and the mid-Pliocene warm period (approximately three million years ago) have been added. Three of these PMIP3 experiments (MH, LGM, LM) have been included as high-priority simulations in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5; Taylor et al. 2012), which provides the framework for coordinated climate change experiments used in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment Report (IPCC AR5).

In May 2012 over 80 scientists from more than 30 institutions gathered at Crewe Hall, a former Jacobean mansion in the English county of Cheshire, for the second general meeting of PMIP3. For the first time, model results for the PMIP3 experiments were shown. Over the course of five days many different aspects of paleoclimatology were examined, from the causes of temperature changes over the last 1000 years to a data-model comparison for the Eocene (56-34 Ma); from changes in Arctic sea ice to tropical Pacific El Niño teleconnections; from multi-model temperature patterns to global climate reconstructions based on pollen data. PMIP has identified some key paleoclimate features, which are relevant to each of the time periods by varying degrees and are also relevant to future climate change. These include climate variability, climate/Earth system sensitivity, polar amplification, and data-model comparison. Significant time was devoted to discussing these topics in break out groups, and new working groups were established to examine these topics in detail through the lifetime of PMIP3.

Integrated quantitative analysis of paleoclimate model simulations and climate reconstructions show that global scale climate models are generally capable of reproducing past climate change. However, many questions remain about the abilities of these models on regional scales. Can they reliably reproduce the large Arctic changes seen in the past? Why does the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation respond differently in different models given the same forcing? Why do the simulated climates of the continental interiors change so little? Discrepancies between model simulations and paleoclimate reconstructions based on observations can arise from a combination of uncertainties in the interpretation of paleoenvironmental observations, uncertainties in the model physics and problems with the experimental design. The PMIP philosophy is that a better understanding of past climates and the workings of the Earth System can only be achieved by addressing each of these sources of uncertainty in an integrated way.

A special issue highlighting many results of the PMIP3 meeting is being prepared for the journal Climate of the Past. The Crewe meeting was hosted by the Universities of Leeds and Bristol, and sponsored by PAGES, SCAR (Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research), NCAS (UK National Centre for Atmospheric Science), The Royal Meteorological Society, The Geological Society, and the UK Meteorological Office.

references

Braconnot P et al. (2012) Nature Climate Change 2: 417-424

Haywood AM et al. (2012) Climate of the Past Discussions 8: 2969-3013

Lunt DJ et al. (2012) Climate of the Past 8: 1717-1736

Taylor KE, Stouffer RJ, Meehl GA (2012) Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 93: 485-498

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2012

PAGES news

David Mattey1, C. Spötl2 and M. Luetscher2

1Department of Earth Sciences, University of London, UK; mattey es.rhul.ac.uk

es.rhul.ac.uk

2Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, University of Innsbruck, Austria

Innsbruck, Austria, 18-21 April 2012

A successful paleoclimate reconstruction based on proxy archives rests not only on understanding how regional climate and local weather patterns are related to variability of the climate proxy, but equally on the understanding of local processes that influence how the climate signal is captured in the archive. Speleothem deposits in caves yield a wealth of proxy data that can be related to changes in atmospheric circulation, precipitation and vegetation.

Monitoring cave environments is key to understanding relationships between weather and the processes that affect calcite precipitation inside caves. These include for example knowledge of the production rate of CO2 in the soil zone and its movement in and out of caves, the relationship between rainfall and the composition and movement of groundwater, and the impact of seasonal changes on the precipitation of carbonate as speleothem. Setting up and maintaining reliable cave monitoring programs presents a challenge in wet caves, which are often remote and difficult to access even for experienced speleologists.

Back in 2009 we held a first workshop on cave monitoring techniques in Gibraltar to discuss the technology that was available and share experiences in best practices among the small group of researchers in this field. Three years later many more groups are involved in cave monitoring and have acquired considerable expertise. In April 2012 we held the 2nd International Cave Monitoring Workshop in Innsbruck bringing together scientists and PhD students from 14 countries to discuss new ideas in methodology and instrumentation.

The workshop provided an informal discussion forum for exchange of experiences covering all practical aspects of cave monitoring. Four main themes were discussed: strategies for monitoring the hydrology and meteorology of cave systems, instrumentation and data logging, sampling and analysis protocols, and in-situ studies of carbonate precipitation and other cave processes. It is clear that some challenges still remain, such as finding a reliable way to precisely measure the relative humidity, and avoiding unwanted interference by insects and other animals as well as humans. However, the three years since the first workshop saw significant advances in the ability to carry out automatic logging and sampling of key parameters using ingenious, custom-built instruments.

Cave monitoring is now being actively carried out in many cave systems over the world (e.g. Fig 1) and clearly shows that every cave has its own “personality” that takes several annual cycles to properly characterize and evaluate. Once this is done, features of the chemical proxy record preserved in speleothem can then be assigned to specific local processes, and thus improve the reliability of climate reconstructions from proxy records.

A day trip to Spannagel Cave, an 11 km-long high-alpine marble cave hosting Europe´s highest show cave, marked the end of the workshop. The workshop organizers are grateful for financial support from the Office of the Vice Rector for Research, the Faculty of Geo- and Atmospheric Sciences and the Research Centre Geodynamics and Geomaterials (all University of Innsbruck, Austria) and Gemini Data Loggers (UK).

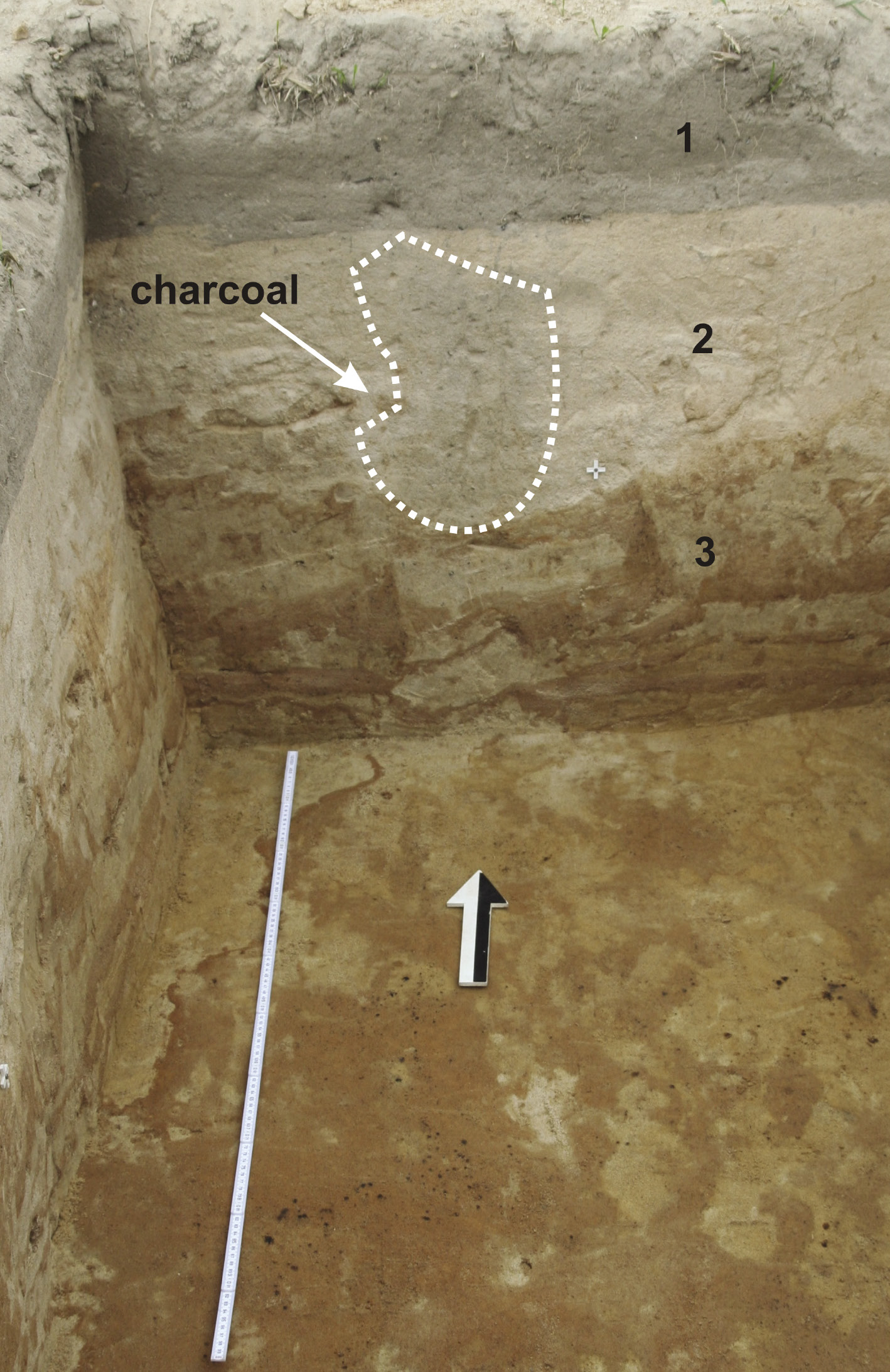

Figure 1: Dripwater collection in Obir Cave, Austria. Photo credit: Robbie Shone (shonephotography.com).

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2012

PAGES news

Daniel G. Gavin1, S. Z. Dobrowski2, A. Hampe3, F. S. Hu4 and F. Rodriguez-Sanchez5

1Department of Geography, University of Oregon, Eugene, USA; dgavin uoregon.edu

uoregon.edu

2Department of Forest Management, University of Montana, Missoula, USA

3Biodiversité, Gènes et Communautés, INRA, Bordeaux, France

4Department of Plant Biology, University of Illinois, Urbana, USA

5Department of Plant Sciences, University of Cambridge, UK

Eugene, USA, 1-3 August 2012

Climate refugia, i.e. areas where populations of a species avert extinction during periods of unfavorable regional climate, may play a central role in maintaining regional-to-global biodiversity. Paleoecologists and biogeographers have a long-standing interest in refugia as a means to explain latitudinal migration or stasis of the geographic distribution of a species through glacial periods and the resulting relictual distributions and endemism (Hampe and Jump 2011). More recently, the burgeoning field of phylogeography has demonstrated the value of genetic information to complement the fossil record in understanding past species distributions. This has lead to increased recognition that far more species than previously thought may have maintained small and scattered populations through the Last Glacial Maximum in refugia situated at relatively high latitude (Stewart et al. 2010). Indeed, a generally low rate of extinction attributable to the dramatic climate change of the Quaternary is not congruent with high rates of future extinction that are projected by many species distribution models (Botkin et al. 2007). The existence of climate refugia in heterogeneous landscapes may provide one solution to this conundrum and contribute to important assessments regarding the risks of future climate change to biodiversity. Specifically, a better knowledge of the functioning and dynamics of historical climate refugia can enhance our understanding of how current populations may react to future climate changes, help with identifying potential refugia for species of concern, and improve our understanding of biotic responses to continued climate warming (Keppel et al. 2012).

We convened a three-day workshop, with support from PAGES and the University of Oregon, to bring together experts from diverse disciplines that provide complementary insights into the identification, characterization, and importance of climate refugia. The workshop engaged 33 participants from 10 countries with backgrounds in paleoecology, climatology, phylogeography, biodiversity research, and species distribution modeling. Three days of meetings were used to discuss advances within each discipline and opportunities for transdisciplinary research approaches.

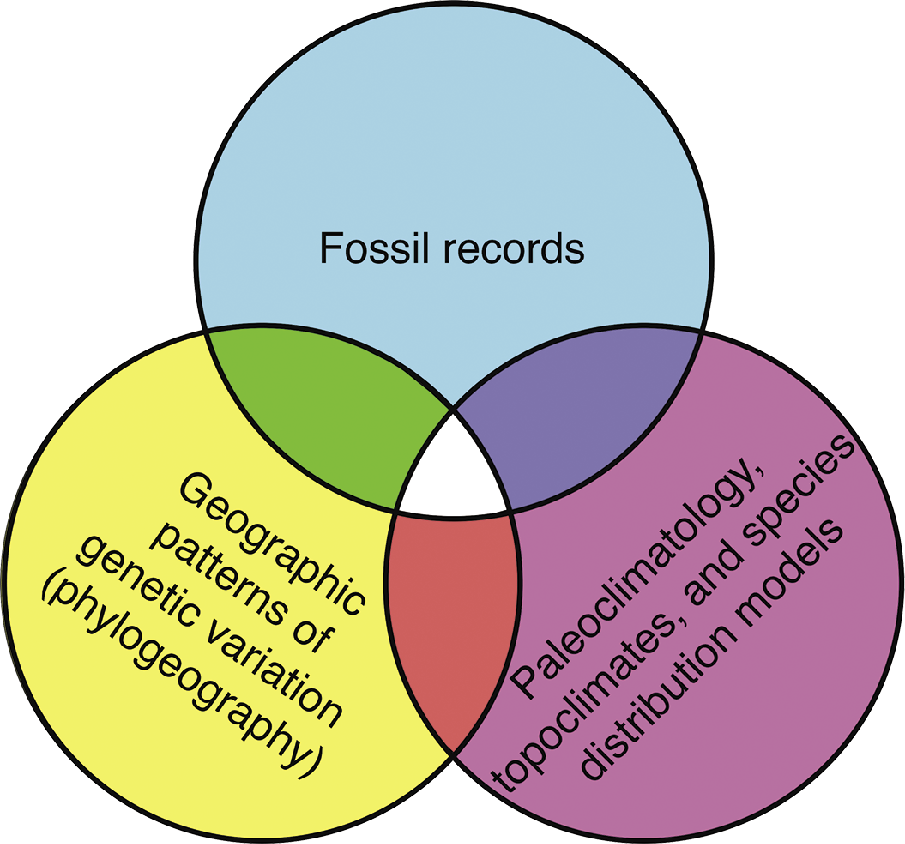

There remains much untapped potential to study climate refugia by using a joint inference across multiple disciplines (Fig. 1). Joint analysis of data across disciplines enables a clearer and more robust picture of species history, as the strengths of the different disciplines are combined. For instance, the fossil record can be used to evaluate the performance of paleoclimate simulations and species distribution models (Varela et al. 2011). Second, hindcasted species distributions have been used to generate hypotheses that can be tested by phylogeographic studies (Richards et al. 2007), or simply to reveal past range dynamics that can explain the current distribution of genetic lineages (e.g. Hugall et al. 2002). The successful application of species distribution modeling to the study of refugia requires not only reliable paleoclimate estimates from coarse-resolution models, but also realistic downscaling of relevant variables over complex terrain in the present and the past (Dobrowski 2011). Phylogeography can notably help to detect small populations (cryptic refugia) and reveal the direction of past population expansions that went undetected in the fossil record, whereas the fossil record can constrain the timing of such expansions and detect past range contractions (i.e. local extinctions; Hu et al. 2009). Where sufficient data exist, a network of fossil sites may be interpreted with respect to the refugia inferred from genetics to constrain the spatial and temporal patterns of postglacial expansion, as has been done for Fagus sylvatica in Europe (Magri et al. 2006). Few studies to date have attempted joint inferences across all three approaches, and a quantitative framework that considers the strengths and weaknesses of each approach is needed for rigorous assessment of past species refugia and migration patterns. Such studies are likely to provide the most informed view of how individual species persisted through the Quaternary and, potentially, into the future.

selected references

Full reference list online under: http://pastglobalchanges.org/products/newsletters/ref2012_2.pdf

Dobrowski SZ (2011) Global Change Biology 17: 1022-1035

Hampe A, Jump AS (2011) Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 42: 313-333

Hu FS, Hampe A, Petit RJ (2009) Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 7: 371-379

Keppel G et al. (2012) Global Ecology and Biogeography 21: 393-404

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2012

PAGES news

Kathy J. Willis1, S. A. Bhagwat2 and E. S. Jeffers1

1Oxford Long-Term Ecology Laboratory, University of Oxford, UK; Kathy.willis zoo.ox.ac.uk

zoo.ox.ac.uk

2School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, UK

Oxford, UK, 9-11 January 2012

The first meeting of the PAGES Focus 4 Biodiversity Theme was co-sponsored by PAGES and the Oxford Martin School Biodiversity Institute. The overall aim of the meeting was to bring together paleoecologists, modelers and neo-ecologists whose research contributes to understanding the dynamics over time and space of biodiversity and ecosystem services. Forty people attended the meeting representing 14 different countries and five continents.

The three-day meeting was split into seven sessions. The first four focused on the presentation of paleo-data relevant to the four key ecosystem services categories (Box 1). Two sessions focused on using the past to assess biodiversity risks in the future, and modeling of long-term data for managing ecosystem services. The final session examined the use of long-term data in ecosystem service valuation and management tools.

In addition to the plenary presentations there were also two breakout sessions, which stimulated discussion on (i) the different types of paleoecological data that are relevant to assessing ecosystem services through time and (ii) the databases and sources already available to enable landscape-scale reconstructions, and the identification of data gaps. The overall conclusion from these breakout sessions was that there is already a vast wealth of excellent data and models available for assessing ecosystem function and service provision through time. The major challenge is to determine the appropriate means to disseminate this information to policy makers, habitat managers, and other academics. In particular, the participants discussed the need to devise new methods to present paleodata in a format that is more accessible, possibly through the development of new data management tools and better web-portals.

The main outputs of the meeting will be an edited volume in The Holocene entitled Dynamics of Ecosystem Services Through Time: Looking to the Past to Plan for the Future. A policy brief is also in progress to communicate the need for a long-term perspective in national and international ecosystem assessments. Future planned activities of the PAGES Biodiversity Theme include a workshop at the International Ecology Congress (INTECOL) 2013 and a second Working Group meeting in Oxford, UK. The recent establishment of the International Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) renders this PAGES Theme and its focus on biodiversity and ecosystem services extremely timely.

Box 1

Ecosystem services are benefits that people obtain from ecosystems and are divided into four categories:

• Supporting services

e.g. dispersal of seeds and pollen, cycling of nutrients, primary production

• Provisioning services

e.g. supply of food, water, pharmaceuticals, energy

• Regulation services

e.g. crop pollination, carbon sequestration, waste decomposition and detoxification

• Cultural Services

e.g. recreational and cultural experiences, scientific discoveries

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2012

PAGES news

Lenka Lisa1, A. Wiśniewski2 and K. Issmer3

1Institute of Geology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Prague, Czech Republic; lisa gli.cas.cz

gli.cas.cz

2Institute of Archaeology, University of Wrocław, Wrocław, Poland;

3Institute Geoecology and Geoinformatics, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland

Poznań, Poland, 25 October 2011

Geoarcheology brings together many disciplines such as geology, geomorphology, archeology, paleobotany or zoology. The traditional geoarcheological approach is based mainly on geological and soil science methods, but during the last 20 years detailed microstratigraphic studies and analyses of microfacies have become more and more important (Courty 2001). These approaches were recognized as essential to recover and understand the full cultural and environmental potential of archeological deposits (Goldberg and Macphail 2006).

The main aim of this workshop was to initiate scientific discussion on the new challenges for geoarcheology in Central Europe. Scientifically, the focus was on ongoing environmental archeology research in southern Poland and the northern Czech Republic, and their implications for paleoclimate research. The presentations mainly concentrated on the Late Pleistocene and Middle to Late Paleolithic (130-12 ka BP), for which archeological evidences are more frequent than for earlier periods.

The organizers had invited a range of specialists from the Czech Republic and Poland to discuss “key” questions of the Late Pleistocene stratigraphy and Paleolithic evidences from southern Poland. Topics addressed ranged from subsistence strategies of Late Paleolithic hunter groups to the MIS3-MIS1 stratigraphical records in the region (Połtowicz-Bobak 2009; Wiśniewski et al. in press; Bobak and Poltowicz-Bobak, in press). In addition, applications of relatively new methodological approaches for the field were presented, such as microstratigraphy, isotopic studies or GIS analyses (see Skrzypek et al. 2011). In total, nine presentations raised questions about chronological accuracy in the context of terrestrial and marine data as well as chronostratigraphy from the view-point of archeology (e.g. Fig 1; Wiśniewski, University of Wrocław; Bobak, University of Rzeszów) and sedimentology (Lisa, Institute of Geology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic; Kalicky, University of Kielce), subsistence strategies in the context of environmental changes (Łanczont, University of Lublin; Madeyska, Polish Academy of Science; Warszawa, Połtowicz-Bobak, University of Rzeszów; e.g. Boguckyj et al. 2009, Sytnyk et al. 2012) and on the paleozoological records of environmental change (Nadachowski, Polish Academy of Sciences; Kraków, University of Wrocław; Nadachowski 2011). Finally, Iwona Hildebrant-Radke (Mickiewicz University Poznań) presented new methodological aspects for the use of GIS in geoarcheological investigations (Jasiewicz and Hildebrand-Radke 2009). The presentations were followed by plenary discussions.

The major outcomes from the meeting in Poznań are plans for a new cooperation, especially within the scope of the study of the Late Paleolithic in the historical region of Silesia. One example is the transfer of methodological knowledge between institutes from the Czech Republic and Poland. The participants agreed to build a network for sharing such information. Until now, the exchange of knowledge between the Polish and Czech groups was rather scant and it was decided that an important step to improve it would be to designate a contact person in each country who will share the information about forthcoming meetings. The contact persons for the Polish part are Katarzyna Issmer and Andrzej Wiśniewski. The contact person on the Czech side is Lenka Lisa. Another approach to facilitate communication in the scientific community is the creation of two virtual groups on the social network Facebook with the title “Quaternary Group” (www.facebook.com/#!/groups/253485648040066/) and “Zooarchaeology and Paleonthology” (www.facebook.com/#!/groups/paleontologie/). Also, a scientific platform for Central Europe was set up (http://geoinfo.amu.edu.pl/sas/en/egp/index.php).

This workshop was supported by the Polish Association for Environmental Archeology and the A. Mickiewicz University in Poznań, and was endorsed by PAGES.

references

Boguckyj AB et al. (2009) Quaternary International 198: 173-194

Jasiewicz J and Hildebrandt-Radke I (2009) Journal of Archaeological Science 36: 2096-2107

Nadachowski A et al. (2011) Quaternary International 243: 204-218

Skrzypek G, Wiśniewski A and Grierson PF (2011) Quaternary Science Reviews 30: 481-487

Wiśniewski A et al. (in press) Quaternary International, doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2011.09.016